Islam without Extremes: A Muslim Case for Liberty (17 page)

Read Islam without Extremes: A Muslim Case for Liberty Online

Authors: Mustafa Akyol

A study on labor in medieval Middle East also reveals this structural shift. Between the eighth and eleventh centuries, the formative period of Islamic law, the Arab-Islamic lands stretching from Iraq to Spain harbored 233 distinct commercial occupations. Later, between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries, there was a slight decline in this number, whereas the occupations in the bureaucracy and the military tripled. There was, clearly, a rise in military and state power, but “inertia in regard to commercial organization.”

32

This periodization in the history of Islamdom suggests that the obstacle to economic progress in this part of the world was not Islam itself, as some essentialists believe. “It was not the attitudes and ideologies inherent in Islam which inhibited the development of a capitalist economy,” notes Sami Zubaida, emeritus professor of sociology at the University of London, “but the political position of the merchant classes vis à vis the dominant military-bureaucratic classes in Islamic societies.”

33

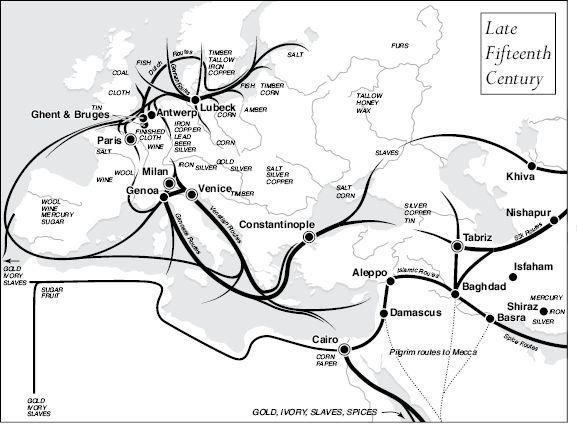

In the later centuries (from the twelfth onward), stagnation would deepen as Islamdom became more and more isolated and as trade, the main engine of dynamism in the Orient, gradually shifted elsewhere. First came “the loss of the Mediterranean,” due to the Crusaders’ occupation of the whole eastern and northeastern coastline of this commercially vital sea. This, argues the great French historian Fernand Braudel, is probably the best explanation for “Islam’s abrupt reverse in the 12th century.”

34

In the thirteenth century, the Mongol catastrophe would impose a much more abrupt, and tragic, reversal.

The final blow would come in the fifteenth century with the Age of Discovery, during which Western Europeans found direct ocean routes to India, China, and elsewhere. Consequently, world trade routes would rapidly shift to the oceans, enriching Western Europe. Not only did this further impoverish the Middle East, it even made the Mediterranean a backwater. This whole northwestern movement of “world capital” between the twelfth and the eighteenth centuries explains, in the apt title of one of Braudel’s essays, “the greatness and decline of Islam.”

35

As trade declined so gradually, and dramatically, there remained only one major factor as a context to shape the Muslims’ understanding of the Qur’anic text: the land of the Middle East—the

arid

Middle East.

D

EEP

D

OWN,

I

T’S

E

VEN THE

E

NVIRONMENT

Throughout this book, I have used the term

Islamdom

. To visualize which part of the world this term describes, search for “Islamic world map” on the Internet. Then please do a second search, for “world aridity map.” You will see an amazing correlation between “Islamic” and “aridity.”

This is a curious phenomenon that led some observers to think that Islam as a religion was particularly suitable to a certain kind of environment—deserts and dry steppes.

36

This is wrong, for Islam has flourished in rainy and fertile lands as well—such as the Far East, the Balkans, and certain parts of Turkey and Iran. But the regions where formative developments in Islam occurred were indeed almost all arid. So, could there be a link between this type of environment and those formative developments?

The late Joseph Schacht, a leading Western scholar on Islamic law, believed so. To explain the Traditionists’ passionate adherence to the idea of the

Sunna

of the Prophet, which we have seen, he referred to their mindset, which was shaped by their physical environment:

The Arabs were, and are, bound by tradition and precedent. Whatever was customary was right and proper; whatever the forefathers had done deserved to be imitated. This was the golden rule of the Arabs whose existence on a narrow margin in an unpropitious environment did not leave them much room for experiments and innovations which might upset the precarious balance of their lives. In this idea of precedent or

sunna

the whole conservatism of the Arabs found expression. . . .

These two maps show how world trade, and the urban cosmopolitanism it fostered, shifted its weight from the Islamic Middle East to Europe between the eighth and fifteenth centuries. (Source: Colin McEvedy, The Penguin Atlas of Medieval History [Harmondsworth, UK, and New York: Penguin Books, 1961], pp. 43 and 89)

[It] presented a formidable obstacle to every innovation, and in order to discredit anything it was, and still is, enough to call it an innovation. Islam, the greatest innovation that Arabia saw, had to overcome this obstacle, and a hard fight it was. But once Islam had prevailed, even among one single group of Arabs, the old conservatism reasserted itself; what had shortly before been an innovation now became the thing to do, a thing hallowed by precedent and tradition, a

sunna

.

37

Consequently, the Arab distaste toward “innovation,” a product of the culture of the desert, in which hardly any innovation lives, crept into Islam and became a part of it. “The worst things are those that are novelties,” read one of the popular Hadiths favored (and probably invented) by the Traditionists. “Every novelty is an innovation, every innovation is an error, and every error leads to Hellfire.”

38

This was not the wisdom of the Prophet, as was thought, but the culture of the desert.

It probably was not an accident that the idea of strict obedience to an all-encompassing Sunna was coming mainly from the Arabs, while most of the Mutazilites were Iraqis or Persians, whose cultural background was Babylonian or Persian, Christian, Zoroastrian, or Manichaean. Therefore, although they were firmly attached to the Qur’an, they were not so willing to “accept Arabian attitudes not considered essential to Islam.”

39

I should note that the term

Arab

in this context refers only to the “original Arabs” of the Arabian Peninsula—the Bedouin. The wider Arabic world of today, stretching from Morocco to the Persian Gulf, is mostly made up of “late Arabs,” who, with the spread of Islam, adopted the Arabic language. I should also note that what we are speaking about here is not any inherent characteristic of any group of people, but rather certain cultural traits formed by the physical terrain where they live. Ibn Khaldun, the fourteenth-century Muslim scholar, was the first to systematically study this matter. “The Arabs, of all people, are least familiar with crafts,” he wrote, for they “are more firmly rooted in desert life and more remote from sedentary civilization.”

40

(Again, the term

Arab

in Ibn Khaldun’s language only referred to the Bedouin.)

In the eighteenth century, Ibn Khaldun’s idea was advanced, probably thanks to some direct connection, by the French liberal Montesquieu.

41

His theory of climate held that the physical environment has great influence on the shaping of cultures. British liberal Adam Smith, too, made similar suggestions.

42

The theory, known as “environmental determinism”—or, in a more modest and accurate version, “environmental possibilism”—became more popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, influencing some Western interpretations of Islam as well. “The Koran is not in itself the conservative force in Islam,” wrote an American scholar in 1924:

Rather is that force the attitude of the Moslem toward his sacred book—and to things in general. Or shall we not say that the ultimate cause is “something more reliable and dependable than the human mind”—the eternal desert, which preserves, as in a museum of antiquities, races, customs, and religions, unchanged as the centuries come and go.

43

The late Sabri Ülgener, the towering figure of economic history and sociology in modern Turkey, also made similar observations on the origin of some cultural attitudes in Middle Eastern societies. “Fatalism,” for example, he noted, “was not the creation of religion and Islam in particular. It was the expression of the weakness of the man of the desert and the steppe in the face of the staggering odds of nature. It merged into Islam, however, and survived under the name and the mask of submission [to God].”

44

Gérard Destanne de Bernis, a French economist who extensively studied rural life in Tunisia, agreed. If “the peasants of the Muslim countries are indeed fatalistic,” he argued, this was not an irrational attitude on their part, but a just estimation of the precarious factors that determine the outcome of their efforts: “Anyone so placed would be fatalistic.”

45

The desert not only produced fatalism and an extreme conservatism distasteful of every “innovation” but also a very literalist conception of language, which had left not much room for a mind open to nuance and allegory,

46

and even a “lack of a sense of aesthetics.”

47

Later in the twentieth century, though, such environmental explanations for culture and development lost their popularity in academia, for they faced accusations—wrongly, in my view—of justifying racism or imperialism. But the idea was “not disproved, only disapproved.”

48

No wonder it is having a comeback in scholarship and in popular literature, with significant books such as David Landes’s

The Wealth and Poverty of Nations

and the Pulitzer-winning

Guns, Germs, and Steel

.

49

“Environment,” notes the latter’s author, Jared Diamond, “molds history.”

50

O

RIENTAL PATRIMONY

The environment molded the history of the Middle East as well—by shaping not just the mindsets of individuals and the cultures of societies but also the political structures of states. One definitive outcome of the aridity of Middle Eastern land was infertility, and hence “the lack of surplus.”

51

This made it impossible for local (i.e., feudal) rulers to gain power. Instead, power was concentrated in central governments that could organize forced labor to build irrigation systems.

52

In addition, much of the Middle East has a “flat” topography on which “armies could march unhindered”—as the Mongol armies tragically did.

53

As a result, even before Islam, this part of the world was ruled for millennia by powerful centralized states.

Now, compare this geopolitical structure with that of Europe, which, unlike the Middle East, was a rainy and fertile continent with plenty of regions that are “hard to conquer, easy to cultivate, and their rivers and seas provide ready trade routes.” This topography, explains Fareed Zakaria,