IT Manager's Handbook: Getting Your New Job Done (61 page)

Read IT Manager's Handbook: Getting Your New Job Done Online

Authors: Bill Holtsnider,Brian D. Jaffe

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Information Management, #Computers, #Information Technology, #Enterprise Applications, #General, #Databases, #Networking

There are no standard answers to these questions and issues. Each organization must consider them and come to a decision about their own priorities. And the answers won't come easily or quickly. It could easily take months just to determine the answers, and all this must happen before you can begin to formulate the actual disaster recovery plans. Because of questions like these, and many more, it's important that the planning not be limited to IT alone.

The committee can serve not only to develop the plan, but also, in the event of a disaster, serve as a decision-making body—one that provides leadership and guidance to the rest of the organization for the duration of the disaster recovery effort.

Application Assessment

To start determining where your technology priorities are, you'll need an inventory of your applications. The items to track for each application in the inventory include:

•

User community (departments, number of users)

•

Vendor

•

Database environment

•

Operating system environment

•

Interfaces to other applications, systems, and vendors/partners

•

Whether the application is considered “critical”

•

Which server(s) the application runs on

•

Which teams support the application

•

Periods of peak/critical usage (days of week, ends of months/quarters, season cycles)

•

Executive usage

•

Who needs to be notified when scheduling downtime or when there is an unexpected outage

•

Where the application installation media and instructions are stored

This inventory will be a critical tool for disaster recovery planning, and essentially helps you develop a business impact analysis. A business impact analysis identifies the areas that may be the most vulnerable and that would cause the greatest loss to the organization. With this information, you can begin to assess, along with other departments, the criticality of your business's applications. See the section

“What Do We Have Here”

in

Chapter 7, Getting Started with the Technical Environment

on

page 189,

for more information about inventories

Compiling all of this information is a lot of work, of course, but you should have done most of this work for other reasons: you need these data to complete the inventory of your technical environment. This topic is discussed in the last section of this chapter entitled

“The Hidden Benefits of Good Disaster Recovery Planning” (page 261

).

You'll want to set up some guidelines for the assessment, probably along the framework of your organization's priorities. For example, if continued customer service is a key priority, you'll have to identify those applications associated with customer service.

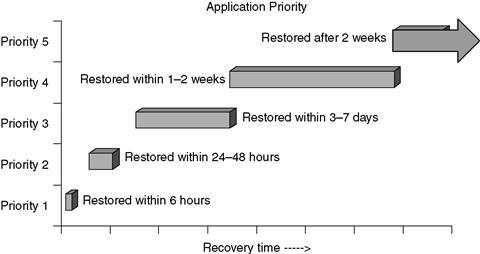

In all likelihood, you'll probably end up with several priorities of applications. An example of those priorities, as shown in

Figure 9.2

, might be:

•

Priority 1: Those applications that need to be returned to service within 6 business hours.

•

Priority 2: Those applications that need to be returned to service within 24 to 48 hours.

•

Priority 3: Those applications that need to be returned to service within 3 to 7 days.

•

Priority 4: Those applications that need to be returned to service within 1 to 2 weeks.

•

Priority 5: Those applications that can wait more than 2 weeks to be returned to service.

Figure 9.2

Sample application recovery priorities.

You may choose to define a Priority Zero for your applications, which would include the core services. This could include items such as a network environment, remote connectivity, Internet access, and DNS and DHCP services. For many organizations, e-mail might be considered a Priority Zero application, along with telephone services.

To help you judge the priorities of your different applications, consider different questions:

•

Are there risks to the

safety

of employees, customers, or the general public with an outage of different applications?

•

Are there any

regulatory costs

associated with an outage to this application? What happens if a requirement isn't met? Is there a financial penalty? Would you be allowed to conduct business if not compliant?

•

What is the

loss to the business

if this system is unavailable? In addition to lost revenue, would there be penalties from partners for missed obligations? Would it impact the company's financial and credit ratings?

•

How big is the concern about

loss of the organization's image or customer/public trust

that may result from an outage?

•

What is the

likelihood of an outage of this application

as a result of different types of disasters?

•

Are there

redundancies

already in place to help mitigate the impact of a disaster? These redundancies could include items such as clustered servers, RAID technology for data storage, and backup generators.

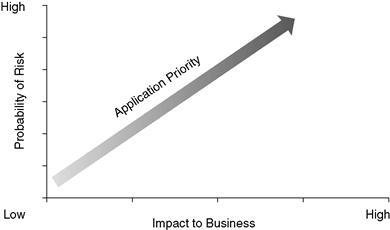

These types of questions force you to consider how big an impact each application, system, or resource has on the organization, as well as the risk probability of different types of disaster. As shown in

Figure 9.3

, the higher the risk and the higher the impact to the business, the higher the priority should be.

Figure 9.3

Application priority for disaster recovery.

Again, the specifics of the application prioritization, as well as the number of priorities, will vary tremendously from organization to organization. And, these may even change depending on the time of year.

The Value of Your Data

At the same time you're considering application priorities, you have to consider how much

data loss

you can tolerate. For example, in a payroll system, it may not be that much of a problem if the last two days of changes have to be reentered (because the last backup available was taken 48 hours prior to the disaster, and not many changes occur on a daily basis). In a brokerage house trading system, however, the tolerance for data loss might be zero, necessitating real-time replication of all data. The volume of data change in these two scenarios is very different.

9.2 Creating a Disaster Recovery Plan

Once you have the scope and identified the critical applications, you can begin to develop a plan. If you expect to have any hope for any level of success in the event of a disaster, several key items must be identified in order to develop that plan.

•

Communication plan:

A plan for contacting key personnel, customers, vendors, and employees.

•

Documentation:

Written material describing the existing environment, procedures for declaring a disaster, procedures for reestablishing services in a disaster recovery mode, etc.

•

Real estate and IT facilities:

Determine which location(s) people should meet up at if the facility is suddenly off-limits, inaccessible, or out of commission. Where can you set up servers and get Internet connectivity?

•

Off-site storage of data:

If your facility is destroyed, or inaccessible, make sure you have an up-to-date copy of your data at an off-site facility.

•

Hardware availability:

Make sure that you can get replacement hardware if yours is destroyed. This list could include workstations, servers, routers, switches, storage (disk and tape), etc.

•

Regular updating and testing:

Your environment changes regularly (technology, people, needs, organization, procedures, etc.). You need to test and update your disaster recovery plan regularly to make sure it retains its value.

Each of these items is discussed in the sections that follow.

Communication Plan

The hallmark of a good disaster recovery plan is good communications. Disasters don't necessarily happen when everyone is sitting at their desks. They can happen on weekends or in the middle of the night. People may be on vacation, at off-site meetings, or in transit.

To ensure that you can get word to people in an emergency, your organization should have a call list that includes information, such as:

•

Home phone number(s)

•

Cell phone number(s)

•

Non-work e-mail address(es)

This list should also include the geographic location of each person's home, as well as cell phone carrier(s). This information could be useful to quickly identify those people that may (or may not) be impacted in an isolated disaster, such as a highway out of service due to a chemical spill or those using a carrier struggling with restoring service.

The list should include individuals from within the company and from outside the company:

•

All members of IT

•

Key executives, customers, and clients

•

Individuals from key departments (Facilities, HR, etc.)

•

Key partners and suppliers (vendors, financial institutions, telecomm carriers, off-site storage facility, etc.)

•

Appropriate regulatory agencies

For some contacts (such as vendors and suppliers), you should also be sure that the list includes appropriate identifying information (such as account numbers) to help avoid delays and confusion. Remember, it is not IT's job alone to put together the contact information; each team and department has responsibility.

The list should exist in electronic form (such as on your phone or handheld device, your PC, or USB memory drive) as well as in paper form in multiple locations (home, office, car, predetermined off-site meeting locations). In a situation where a large number of individuals have to be contacted, a phone tree can be used. Alternatively (or in addition), you can use a third-party crisis communications service such as Send Word Now (

www.sendwordnow.com

) or Everbridge (

www.everbridge.com

), which can facilitate communications to very large groups of people quickly through multiple means (phone, e-mail, text messages). Similarly, a web site set up specifically for providing information in an emergency can be invaluable. A web site like this should be hosted external to your facility to ensure that it can be reached if your facility is off-line. Of course, such a web site has to be secured properly so that sensitive and critical information isn't available to unauthorized individuals, and hosted separately from your regular IT environment so that it stays up while the rest of the environment is down.

Documentation

Thorough and up-to-date disaster recovery documentation is the foundation of an effective disaster recovery plan. Although the document can be distributed electronically, as discussed in the previous section, it should also be distributed in hard copy as well. After all, in the event of a disaster, there is no certainty that you'll be able to access the electronic version. (We don't like to admit it, but sometimes that note you scribbled on the back of a restaurant receipt ends up being more accessible and more useful than that Outlook reminder you sent yourself last Thursday.)

Key individuals should have at least two copies—one copy in their office and one in their home—since there is no guarantee that a disaster will happen between 9 and 5 on a business day. Finally, keep a copy with your off-site backup tapes at locations that can be used during a disaster.