Jellied Eels and Zeppelins

Jellied Eels and Zeppelins

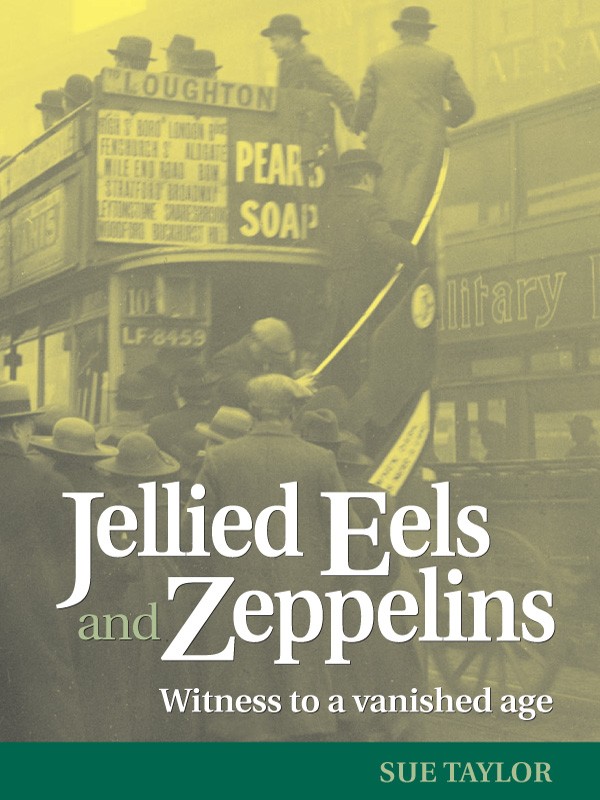

Jellied Eels and ZeppelinsWitness to a vanished age

First published in 2003 by

Thorogood Publishing Ltd

10-12 Rivington Street

London EC2A 3DU

Telephone: 020 7749 4748

Fax: 020 7729 6110

Email:

[email protected]

Web:

www.thorogoodpublishing.co.uk

© Sue Taylor 2003

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed upon the subsequent purchaser.

No responsibility for loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of any material in this publication can be accepted by the author or publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978-185418606-5

ePub ISBN 978-1854187017-0

ePub created by Thorogood Publishing Ltd

For Mum, Dad and Ethel

Writing this book was never going to be easy. I mean, how do you cram more than 90 years of someone’s life into the pages of a book? Ethel’s recollections are countless. However, we had to stop somewhere and had it not been for the help of the following people, compiling the book would have certainly proved more difficult:

BBC Essex, Angie and my mother-in-law, Dorothy (known as Dot), for first putting me in contact with Ethel; and Dot also for her knowledge of the East End and the Second World War; my family and friends for all their support, especially Hayley and Gaynor for their computer skills; Ethel’s friends, relatives and neighbours for looking after her so well, especially Rosemary, who often made notes when Ethel remembered something in my absence; staff at the London Borough of Waltham Council and at the Vestry House Museum for assisting with my enquiries; all at Thorogood (especially Angela), and at Acorn Magazines (especially Pippa); and last, but by no means least, Ethel herself, for her kindness, sense of humour and friendship, and for making my visits so enjoyable. Thank you Ethel, for sharing your memories.

Sue Taylor

In the summer of 1999, Ethel May Elvin was sitting in her cosy kitchen listening to the radio. She had it tuned to BBC Essex when an elderly lady phoned in to talk about life during the 20th century. Ethel was then in her 90th year, older than the caller and yearning to relate her own experiences. Indeed, friends and relatives had often encouraged her to write her memoirs, but with poor eyesight (she had cataracts at the time, but has since had them removed) and arthritis in her hands and legs (caused, she believes ‘by sitting in the dugouts during the Blitz with me feet in water!’), she realised that she needed some help. So, with the assistance of the BBC Essex Helpline and my attentive mother-in-law and her friend Angie who had been listening, I was put in contact with Ethel and recorded the first of many interviews on 17th August 1999. The resultant six articles were published in the Essex Magazine in 2001.

Since our first meeting, I have come not only to admire, respect and be amazed by Ethel’s remarkable memory, but to regard her as a special friend and a truly inspirational character.

That Ethel survived at all - considering the fact that she was a child of ‘delicate health’ and escaped the dreaded ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic of 1918/1919 as well as both World Wars, including the London Blitz, is a feat in itself. That she should have come out of it with such an amazing capacity to laugh - even now that she is housebound for most of the time - is incredible.

This book is one woman’s journey through life in the 20th century from Walthamstow E17, where she was at first her father’s unwanted daughter, to Doddinghurst village, just a few miles north of Brentwood, Essex, where she and her husband, Joe, made the bricks to build their own house. There might not be many miles between the two places, but there are certainly many memories during this long journey. ‘Jellied Eels and Zeppelins’ is a tribute to all those who helped Ethel on her way. I feel immensely privileged to have worked on it. Not only have I got to know a most remarkable lady, but I have been able to gain an invaluable first-hand insight into what life was like for ordinary working-class families from the beginning of the 1900’s.

Ethel Elvin as a young woman

But Ethel isn’t ‘ordinary’ - not really, not by today’s standards. She, and many others of her generation, showed - and still do - immense courage, fortitude and spirit, not only when it was needed, but throughout their lives.

This is Ethel’s story, told mostly in her own words with respect and devotion, sorrow and acceptance, humour and tenacity. It’s in her words, because it’s better that way.

Some of the names of the people in this book have been changed to protect their right to privacy.

Sue Taylor

1909-1923

One

Chocolates and Shoe Leather

‘I was born at Cassiobury Road, Walthamstow, on 16th November 1909, to Edwin and Florence Turner, and was of such delicate health that my mother received an extra four shillings a week from the War Office for me.

When I had a bath, Mum said that I made her feel sick, I was so skinny. My sister, Florrie, was the fat one. She had a podgy face and she used to play with the kids in the garden. She was the king of the kids at our school, she used to be the boss, ‘cos she was the eldest.

Cousin Flo’s mum brought me into the world. Dad wouldn’t look at me ‘til I was a year old. Uncle Charlie - Dad’s eldest brother - lived downstairs and Mum and Dad lived upstairs, and he came home from work and came up to my Mum in bed and said ‘What yer got?’ Mum said ‘Another girl.’ Uncle Charlie said ‘What’s Ted got to say about that?’ My mum said ‘He won’t even look at ‘er.’ Charlie said ‘Miserable ol’ so-and-so!’ Mother said that Dad was so mad that she’d had another girl that he stomped into the kitchen and the china fell off the dresser and made me nervous. I had a touch of what they called St. Vitus’s dance over it when I was a baby.

You know what Uncle Charlie did? We ‘ad four brass knobs on the bedpost. He went out and bought me a pair of little mittens and a pair of socks and stuck ‘em on each of the knobs and said ‘There you are, you poor little soul. If your father won’t buy you anything, then I will!’

In about 1916, Mum miscarried a boy. I think I was about six. Dad put me down all the same… But I remember that Cousin Flo’s brother, Herbert, when he was born, he was that tiny, you could have put him in a pint jug. My Dad wanted to adopt him when Aunt Flo died and my uncle said ‘No, you’re not going to have my son just ‘cos you can’t have one of your own!’ And I remember that so clearly. My Dad wanted to adopt him and that stuck in my mind. Funny isn’t it?’

Ethel believes that her father’s wish for a son in an age when men did most of the manual work, was why he taught her how to

‘mend shoes, hang wallpaper and bang in nails. It was always me who had to help ‘im, never Florrie.’

Ethel remembers helping her father mend their shoes:

‘It was the first time he called me Jane. I was only about six or seven. I never questioned him and, after that, he always called me Jane and I never knew why.’

Edwin’s way, like many others of his generation, was never to show affection:

‘He never kissed me once and I never kissed him. He showed Florrie more affection than me. And yet, when he was ill in hospital towards the end of his life, he turned to me and said ‘You’ve been a good daughter to me’. But I did have great respect for my father. I always did as I was told. The only time I ever answered him back was when I was 24 and broke up with a chap that he liked. Florrie argued with him a bit, but not me. We never held much conversation with Dad. He just used to tell you what you had to do. ‘Jane!!’ he used to shout in his booming voice. When I looked after him in his later years, when he was being stubborn, he said once ‘Don’t you talk to me like that, you’re my daughter!’ I said ‘Yes, and I’m an old age pensioner too!!’

1910: Ethel Elvin’s mother, father and sister Florrie. Ethel is on her mother’s knee

He had a voice that boomed ‘cos of his time in the army during the First World War, when he told the men what to do. He frightened the life out of me when he shouted. I only had to look in his icy blue eyes and I was gone. He had that Sergeant Major look, I used to call it, and that was enough. I never used to stop and argue. I knew better than that. He didn’t believe in hitting kiddies though.’