Jellied Eels and Zeppelins (7 page)

Florrie and Alf late 1920s

I never forget, it was during the time that I was making those horns, that I was taking Grandad his dinner - he used to live near us then - when I got hit in the eye with a big spinning top that the kids were playing with in the road. They were ‘sending messages’ they called it - they used to pull this cord and throw the top and I happened to be in the firing line. The next day, I had a black eye and, when I went to work, the manager came up and said ‘What have you done to your eye - yer ‘usband hit yer?’ I said ‘I’m not married yet!’ Everyone laughed. I was only 14!

I can see it as if it were only yesterday - Mum catching Florrie and Cousin Flo smoking Lucky Dreams in our front-room when they were teenagers. I remember the packet - it was a lovely blue packet, bluey-mauve with a woman dancing in Indian dress. Mum said ‘You can put those out or get out!!’ Mum was very strict about that sort of thing.

Dad was very strict about boys. If I went out in the evening, I had to be back by 10. If I was even the tiniest bit late, I would be in for a tongue-lashing and be docked the amount of time I was late for the next time I went out. When I went out with a boyfriend, I still had to be home by the allocated time and my Dad used to see the shadow of us coming up the garden path and he would be at the front door almost before we got there. There was never any chance of ‘hanky panky’!

I once wore a dress with a two-inch split up from the hem. As soon as Dad saw me wearing it one evening, he made me sew it up before he would permit me to go out. He would not allow petticoats to be seen below hems.

We never thought of having pre-marital sex, for, if you were not a virgin on your wedding day, you were classed as the lowest of the low.

I remember there was a young girl once. Her father always used to get blind drunk at The Standard every Saturday night. My Dad used to see him when he walked our elk-hound, Laddie, past Coppermill Lane School. He came home one night and said ‘There’ll be trouble there,’ ‘cos the mother used to go and fetch him home and the girl was left to run around the streets. She always had a load of boys around her, even though she was only 12 or 13.

One morning, my mother met her mother coming along when she was going shopping up the market. I must have been about 17 then - it was after my sister had got married. Mum asked her how she was and she said ‘I’m in a hurry - my daughter’s been queer and I’ve left her with a neighbour and must hurry back to see how she is, ‘cos she worried me.’ My Mum didn’t see the woman for some weeks after that and, when she did, the woman said ‘You know that day I saw you? When I got home, my neighbour told me to get the doctor. When I asked her why, she told me that she was having a baby.’ Yet that girl wasn’t yet 14. Her mother said that she never saw no change in her whatsoever. That woman brought the baby up as her own. Years later, the girl had a flat down our road. She had married another man - nobody knew who the father of the baby was and I never knew what happened to it.

I wasn’t like that at all. In fact, Dad told us that if we ever got into trouble, we’d be out! I remember at work in the factory one day, a male colleague walked past me and slapped my bottom. I objected, as that was not allowed, and reported him to my foreman, who thoroughly reprimanded the man. Even though the other girls did not like anything like that happening, I was the only one who ever reported an incident of that kind and for that I was labelled ‘The Prude.’

I was 15 when I started going out with this chap called Bobby. I met him at Ensign. He worked in a different department. I got engaged to him when I was 18 or 19, something like that. If we went to the pictures, he would pay to get in and I would buy the sweets. I used to sit indoors waiting for him to turn up. My friend, Doris, used to say ‘He’s pulling your leg,’ but I wanted evidence that he was cheating on me. I was with him for seven years in all.

One year, we had to make some royal blue box cameras for Black Cat cigarettes. They were giving them away if you saved so many coupons in packets of cigarettes. To get this big quota out, we had to work all over Easter, then we could have bank holiday Monday off. So I thought ‘That’s good,’ ‘cos I was saving up to get married.

Anyway, when I told this chap that I would be working, he said ‘We’ll go out on Monday then. I’ll be down for you at 2 o’clock and we’ll go to the fair at Lea Bridge Road, Leyton. (My Mum and Dad had gone down to my sister’s for the weekend.) By 6 o’clock, he still hadn’t turned up. When he did eventually come round, I asked him where he had been. ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘I popped round to my uncle’s and couldn’t get away.’ I noticed that he had dust all over his boots, so I asked ‘How did you get your boots so dirty?’ He said ‘That was when I walked round to my uncle’s. I took a short cut.’ So I left it at that.

We never went to the fair - we just went for a walk. On Tuesday, when I went back to work, I spoke to a friend of mine, Lily, who seemed pretty reasonable, and asked her how she enjoyed her bank holiday. She replied ‘My friend and I went out and we went to the fair. And we met two fellas. We didn’t leave there ‘til gone five. We stung ‘em proper for money. And, do you know the field opposite?’ (There was this field opposite, you could walk through there and that used to bring you to the top of my road in Coppermill Lane, near the reservoir). ‘Well,’ she said, ‘My friend was waiting for the bus and the chap that was with me, walked me across the field and started taking liberties, so I hit him on the chin and knocked him out!’ (Lily was a Cockney, you know.) ‘Rotten devil - wanted to make us pay for the money he’d spent on us, I suppose.’ And then she asked ‘What did you do on your bank holiday Ethel?’

While I was telling her what had happened, I showed her a photo with Bobby in it. She said ‘That chap in the back row. Is he a friend of yours?’ ‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘Well, fancy picking someone like that,’ she said. ‘How do you mean?’ I said. ‘Well, you know that fella over the field? That was ‘im!’ When I told her that he was my fiancé, she said ‘Oh, I’m sorry, perhaps I made a mistake.’ But I said ‘No, you haven’t made a mistake, I have,’ and I packed him up straight away after that. I had my proof.

When Dad asked me why I had finished with Bobby, I said ‘I have my reasons. I’m not a child.’ Dad liked Bobby, and I’m sure that Bobby had told him a different story as to why we had broken up, saying that it was me who had been out with another fella, when in fact I had been out with a girlfriend one evening.

Dad wasn’t happy and accused

me

of cheating. We had an almighty row and I told him - and it was the first time I had ever answered my father back - ‘Don’t accuse others of what you did yourself!’ (I think he thought that I’d forgotten about his affair during the First World War). He went quiet and then I said ‘The way you’re speaking, it’s as if I wasn’t your daughter.’ And you know what he said? ‘Perhaps you’re not,’ and my mother sat in the armchair and sobbed her heart out. I’ll never forget that as long as I live.

I put my hand out to slap my father’s face, but stopped saying ‘No, I can’t ‘cos you’re my father.’ I turned to my mother and said ‘Look, I’m earning enough money to keep meself. I’ll get a place and you can come and live with me.’ But she said ‘I won’t leave my husband.’

I didn’t go out with anybody for about six months after that and then I met Joe, whom I was later to marry. He had got a job in the woodyard that was attached to Ensign and he used to ride a motor bike. He used to stack the wet planks of wood in special drying sheds or kilns as they were delivered, and made desks and dressing tables and all that. Before that, he worked as a builder making shop-fronts for the Co-op.

Well, I’d been out with Joe on his motor bike and he had just brought me home. As I got me leg over the bike to get off, I felt someone’s hands around me throat. It was Bobby. I didn’t know what to do, so I stuck me two elbows in his ribs and pushed ‘im off. He staggered a bit. Joe was facing the other way and, by the time he realised what had happened, Bobby had run off. He was a runner with the Essex Beagles and boy, could he run. Joe said that we’d race after him on the motor bike, but I was so shaken, I just wanted to go home.

Dad was having his Sunday afternoon nap, when Joe rang the doorbell and said ‘Look after your daughter, something’s wrong!’ He went after him on the bike, but Bobby must have caught the bus at the top of the road.

We reported the incident to the police and they warned Bobby never to interfere with me again. The copper was at the factory gates every day for a fortnight, but there was no more trouble. However, Bobby’s father was a boxer, and I did hear that he gave him a right telling off. After that incident, I had terrible pains in my stomach and was under the doctor for three years.’

Strikes, Frosts and a Total Eclipse

In May 1926 a General Strike was called and more than two million unionists stopped work in support of the miners. Ethel’s father, who was working for Lipton’s, came out in sympathy even though he did not belong to a union.

The strike lasted a mere ten days, but its effect on Edwin and his family was felt for much longer. For six months, their only income was that earned by his daughters.

‘Mum added a bit extra by making and selling her paper flowers, like the ones she made for Florrie and I at the Peace Tea at the end of World War I. I’ve still got the button hook she used. She would cut the leaves of the chrysanthemums, put the button hook at the end and pull it down the leaf to make it crinkle.

For our Christmas dinner in 1926, the man next door, who was employed by the gas works, gave us half of his beef joint, as he was better off than us. With her paper flower money, Mum was able to buy the fruit for our Christmas pudding. I remember taking all the stones out of the sultanas - it made my fingers really sore!

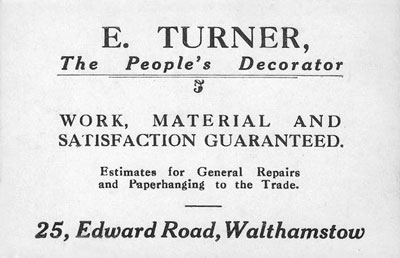

The following year, Dad started up his own decorating business - ‘E. Turner - The People’s Decorator’ - and then he joined his brother-in-law, Fred, as a decorator in his firm, Nicholls and Sons. All their work was done at Hatch End, Pinner, where a lot of the film stars and opera singers used to live. After two years, Lipton’s offered Dad his old job back.

Edwin’s business card

Dad used to go out early at 6 o’clock in the morning. During the winter of 1926, we had what was called the silver frost. Dad knocked on our bedroom door and he said ‘Get up you girls! You’ve got to slide to work this morning.’ He told us to put old socks on our shoes to enable our feet to grip better on the pavements. He said ‘Keep going at a trot and you won’t fall over.’ We did this and we was very lucky not to fall over, ‘cos Florrie and I also had to carry our dinners with us. We generally used to take our dinner down to our canteen at work and heat it up. I had sausage and mash in a basin under me arm and my sister had a flask as we would have a cuppa in the morning (we were never allowed to stop work for cups of tea though, just to go to the toilet). I got a fit of the giggles at work afterwards just thinking about it!

The silver frost was unbelievable - the sight outside. Everything was absolutely white - telegraph poles, everything was shining with silver. I’d never seen anything like it.

Alice, one of the twins who lived in the flat upstairs, worked at Waterlows in London, where they used to make the banknotes. Alice and Dad caught the same train from St. James Street, Walthamstow, to Old Street, London, where Dad would pick up his van. They would walk up the road together.

The houses at the top of the road had five stone steps and, as they walked by, a woman opened her front door and came down the steps to the gate to fetch the milk (that’s when we used to have three milk deliveries a day, if we wanted it!) As she did so, she slipped on the icy steps and her nightdress went up over her head. Alice covered her eyes when Dad said ‘Don’t look Alice!’ He went and helped the woman up and pulled her nightdress back down again. I can always remember him telling us that. It was funny, that was!

I also remember my mother placing some small sheets of glass over tiles in the kitchen and smoking the glass by holding a candle over them. This was to protect our eyes whilst watching the total eclipse in 1927.’

Friends, Fun and Frolics

When Ethel was about 17, she had an encounter with a pet blackbird, which her paternal grandfather once found on his allotment:

‘My grandfather used to go down to the allotment and pick young fresh dandelion leaves to use as lettuce. He never bought lettuce. ‘Dandelion leaves are much better than lettuce,’ he said. He hardly ever ate fried eggs either. When he used to fry a bit of bacon, he used apple rings instead of eggs to go with it. That was his breakfast on Sunday mornings.

Anyway, one morning, he discovered a young blackbird on the allotment. It had obviously been abandoned, so he took it home with him and looked after it until it got bigger. As he didn’t like keeping it in a cage in his flat, he gave it to my Dad. The bird wouldn’t have lived in the wild again, ‘cos it was so tame. My Dad hung the cage outside by the brick wall of the outside toilet in the summer and used to take it inside in the winter. One autumn, I’d gathered a lot of blackberries to make some wine with. I’d strained them and was going to strain them again that night. I was wearing a nice cream linen dress for work and the wine was on the table covered with a bit of muslin. The blackbird’s cage had been brought into the kitchen, because it was getting cold, and Dad had given the bird a snail to eat, which it did using the stone in its cage to crack open the shell.