Jellied Eels and Zeppelins (5 page)

Dad really had a way with animals and he especially loved horses. He told me ‘Never hit a horse, ‘cos they always remember.’

Dad and his mates also used to keep watch on the Channel for anything unusual. They were away from the fighting.’

During his spare-time, Edwin and his friends used to sit on the rocks and wait for the ormer tide to come in bringing with it the ormers - edible abalones (marine snails), also called sea-ears, which have flattened, oval-shaped shells with respiratory holes and a mother-of-pearl lining, and are used as a food in the Channel Islands.

‘Dad was a very good swimmer and diver and he and his friends used to dive into the water before the shellfish stuck themselves onto the rocks and then they wouldn’t have been able to get them off. The shellfish were like oysters, but with knobbly bits on the outside. They had mother-of-pearl inside and Dad brought us all the shells back. They were different sizes and the fish were delicious when fried.

He also used to buy lots of tomatoes and grapes from St. Peter Port (

Guernsey’s capital

) and bring them home for us kids and there were these large biscuits, which looked like dogs’ biscuits, but they tasted lovely too.

I was about six or seven when Dad has his affair. When he used to come home on leave during the war, he would go straight round to this woman’s and my Mum found out. She went round there and said ‘You ought to be ashamed of yourself - you’ve got a husband fighting on the front-line and you’re taking my husband away!’ I think it only lasted for three or four months, but I did lose a certain amount of respect for my father over it. I couldn’t help it. My mother was a good wife to him, she was. She thought the world of my Dad. She looked after us kids ever so well too and never took a day off. And that’s all the thanks that she got.

On the huge field called The Elms at the back of our flat in Walthamstow, where we used to go and pick up the tennis balls for a penny, there were specially erected tents, where they made mustard gas bombs. My Dad came home on leave once and Florrie and I had just come home from school. Dad asked ‘Where’s your mother?’ and Florrie replied ‘On The Elms making bombs!’ Dad said ‘Right - I’ll make a bomb!’ and he went and dragged her out, shouting ‘You’re not making those sorts of things and you’re not leaving those two kids! I didn’t marry you to go off to work. Get home and look after the girls!’

A lady up the road took the job and Mum looked after her two children, so she had the four of us and did her little bit that way.’

With no television or radio to follow the events of the Great War, British families either had to scan the newspapers or watch the Pathé News at the cinema:

‘We always used to go on a Friday night. It used to cost threepence to watch the Pathé. My sister and I, when we was younger, we used to go to the Saturday morning pictures - that cost a penny. We would get a comic or an orange when we came out. They always cut the film off at the most exciting part to make sure that you went back the next week. The Carlton Cinema was a lovely cinema opposite the Walthamstow Palace. There was the Sarsaparilla Stall outside, where when we was older, we used to have a glass of sarsaparilla before we went in. St. James Street Cinema was a flea pit. It was known as ‘The Jameos’ and you used to see serials there. We used to pay for ourselves to get into the cinema - a penny. My Dad gave us our ‘Saturday penny’ for washing and drying-up and for cleaning the knives and forks on an emery board. And that penny, or the penny we were given by anyone who came to visit, was split by Dad into two ha’pennies or four farthings.

We had two money boxes like pillar boxes on our mantelpiece marked ‘F’ for Florrie and ‘E’ for Ethel. We used to put a ha’penny in there every Saturday, but, if we went to the pictures, we’d use the whole penny. With the two farthings we had, we’d get two lots of sweets. Two we saved and two we could spend. Sometimes Mum borrowed our money, but she would always pay us back. I can see her now putting a knife in the slot of the box to get the pennies out. ‘Look girls,’ she would say afterwards, ‘I’m putting it back!’

When I was two and a half, Mum took me into the post office. I put my hands on the counter and I could just see over the top. She gave me a book just like a pension book and it had 12 spaces in it. Mum said ‘Each one of those spaces is a penny - when you’ve got a bookful, you’ve saved one shilling. That’s your savings book.’ I saved from when I was two and a half to when I got married and I spent it all on my wedding and on some of the furniture, the curtains, lino, the lot - it even paid for my car to the church. My chap hadn’t got it, so I paid it.’

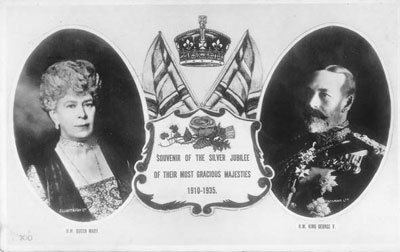

A souvenir of the silver jubilee

The King and Queen during the First World War were George V - who succeeded to the throne on the death of Edward VII in 1910 - and Queen Mary, whom he had married in 1893.

‘He was very nice, but she was a domineering woman. Queen Mary always seemed very stuck-up and strait-laced. She always had one of those hats on her head and she used to walk with a parasol. The King would do as he was told and always did the right thing.

Gran (Aunt Polly) and Grandad (paternal) were the caretakers of a big old house in Bramham Gardens, Earls Court, before and for a while during, the First World War. It was a big five-storey house - I can see it now - and Gran and Grandfather lived in the basement. Gran was the cook and Grandfather was the butler. I can remember going down into the kitchen looking for Grandfather once. There was an iron spiral staircase at one end. Grandad was sitting at the top playing ‘The Merry Widow’ on this brass thing like a bicycle wheel, like a hurdy-gurdy. That song has stuck in my mind ever since.

Grandfather’s nickname for me was ‘Pins and Needles’, because he said that I could never sit down for five minutes (I think it was because of the St. Vitus’s dance I had when I was a baby!).

Us children weren’t allowed to go upstairs, only when requested by the family. We used to have to curtsey. Gran caught me going upstairs once without permission and she told me off. Right at the very top of the house was the nursery. Gran took me upstairs once and I remember seeing all these dolls in glass cases all the way round.

Bramham Gardens, Earls Court, London

It really was like that television programme, ‘Upstairs Downstairs.’ Downstairs there were six bells along the kitchen wall and an electric light up in the ceiling. When they wanted to see anything at close range, they used to pull it down on a pulley, right onto the table, so they could see what they were doing. There was a big butler sink too - it was very posh. Gran used to buy pigs’ chitterlings (

the smaller intestines of pigs

), put them in salt water, clean ‘em and fill ‘em with sausage meat and cook ‘em for the downstairs’ staff. They were lovely. There was also a real sunken garden full of fuchsias with another big garden further on.

The German Baron and his family, who owned the house, also owned another at Littlehampton. Grandfather used to stay there for a couple of days to clean the windows and tend to the garden there.

My sister, Cousin Flo and Cousin Charlie were allowed to stay with Gran and Grandad, but I wasn’t - I suppose I was too young. I was about two years old, when Gran had them for about a week. They were all dressed up - I remember my sister walking up these steps to the front door of the house, with this lovely red outfit on: a red hat with white fur on it and a red coat; and Charlie had a new suit. I stood by the gate, holding my Mum’s hand, watching them.

I did join them once for a few hours when I must have been about four. It must have been on a Sunday and Gran had bought us girls new hats to go to church in. They were like straw panama hats with white ribbons on the front. Gran had a parrot named Dolly and Charlie was tormenting her. Dolly got so flustered that she tipped her seed all over the floor. As I bent down to pick up the seed, the parrot pecked a big hole in my new hat!

When war broke out, the Baron had to leave the house, though Gran and Grandad stayed on for a while to sort out the family’s belongings. The family gave my sister a doll… a German doll, beautiful it was. It was dressed in a blue crêpe dress and I can see it now - there was a red ring with a red stone on one of the doll’s fingers, red earrings and a red bracelet, beautiful black curls, a little cloak, a hat and shoes. They used to make lovely faces on dolls years ago, the Germans - natural, beautiful, they were. I was really envious, ‘cos I didn’t get one. They also gave us a pram with a long china handle and a green cover. My sister used to put her doll in it and wouldn’t allow me to push it.’

The doll was eventually passed down to Florrie’s great granddaughter and when Ethel happened to spot it in her bedroom on a visit, she told the little girl the doll’s story:

‘The dress had faded from its original colour to a pale lavender, but its face was still beautiful. They were astounded that I’d remembered it.

The German Baron didn’t come back to Bramham Gardens, so he said ‘sell the house,’ so the house was sold and Gran and Grandad went and worked at Philbeach Gardens in the same area, Earls Court.’

Although rationing during World War I was not as extensive as it was during World War II, food shortages were experienced throughout Britain, especially after the bad harvests of 1916.

‘I can remember lining up for potatoes for what seemed like hours, my sister and I, outside Giddens, the greengrocer’s, at about eight in the morning. They were brothers and had a shop at either end of the street. Florrie stood at one end and me at the other. When one of us had to go to school, Mum took her place in the queue. Sometimes, she would try to dodge in, so that she would get two lots, one for us and one for Mrs Dawson next door. I think they used to allow us about two pounds each of potatoes. We used to have the old swedes after that.

There was a family living opposite us. Their name was Vesey. The mother was German and the father, Turkish. They were the nicest people you could ever wish to meet - a lovely, beautiful family. There were six children, two girls and four boys … all teenagers they were. Well, when the war started, those boys went overseas and fought their German cousins. One of the sons got injured and, when he returned home, became a cinema operator.

After the war, when the old soldiers used to come round the streets singing for a few coppers, the mother would never let them pass without giving them money. And she would take them indoors and give them a cup of tea.’

During the First World War, rioting occurred in many areas where German families were living. A German pork butcher named Muckenfuss was one of those affected:

‘Another German was a butcher in our market. I remember holding my Mum’s hand when I was about six years old. We was going shopping in St. James Street during the First World War. There was a lot of shouting going on in the street. Mum said ‘Come on, we’ll get away from here.’ I saw many people around the butcher’s shop. Some of the men then went upstairs to the flat and threw the piano out of the window. I remember it coming down and, just before it crashed onto the pavement, my Mum pulled me away. I think he moved away after that.’

It was estimated that the Great War claimed 10 million lives. But, in 1918, the year it ended, doctors were claiming that the so-called ‘Spanish Flu’ was killing even more people worldwide.

‘Aunt Flo, when she was carrying again, she died of it and Cousin Flo caught it as well. She was very ill and we thought we were going to lose her too. My Mum went round there and nursed her, so my sister stood on a box and I stood on a stool, and we put a big tub on another box and we did the washing while Mum was looking after Flo and the others. And, when she got better, my Mum caught it and my sister and I nursed our mother.

Cousin Flo lost every hair on her head and wouldn’t go to work, cos’ she’d got a bald head and Mum - she told me this herself - mixed old-fashioned brilliantine with paraffin and rubbed it in Flo’s head every day. She said ‘I’ve got Flo’s hair growing!’

We used to call Flo Fanny Nine Hairs! She went to work with a frilly mop hat that Mum made for her out of shantung (

heavy Chinese silk

). My Mum saved her life.