Jessen & Richter (Eds.) (70 page)

Read Jessen & Richter (Eds.) Online

Authors: Voting for Hitler,Stalin; Elections Under 20th Century Dictatorships (2011)

“ G E R M A N Y T O T A L L Y N A T I O N A L S O C I A L I S T ”

267

counted in Schleswig-Holstein; mainly by counting ballot papers without a

cross as a “yes”-vote for the NSDAP. Taking this into account, the

number of votes against the regime in 1936 was probably just as high as it

was in 1934, which indicates some degree of continuity in non-conform

voting behavior at least for the region of Schleswig-Holstein. It is not easy

to determine whether these findings also apply to other parts of the

Reich

because comparable data are still lacking. All in all, social control grew

from election to election both in front of and inside the polling station,

and increased the pressure to vote “yes” to such an extent that at least

from 1934 onwards there was no such thing as a

free

vote in the

Reich

.

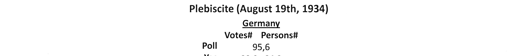

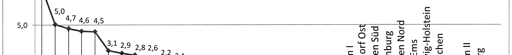

Analysis of Election Results

It is worth looking more closely at the results of the ballots of 1933 and

1934, since it was still possible then to vote against the Nazi regime. By

analyzing the election results at constituency and polling-station level, we

can make clear the extent of deviant voting behavior at local level. Since I

have produced detailed statistical analyses elsewhere, I will confine myself

here to a few key findings (Omland 2006a).27 My evaluation of election

results is based on the number of those entitled to vote and not on the

number of valid votes cast. Distortions due to electoral participation are

thereby avoided. My analysis is based on the model suggested by Otmar

Jung, which focuses on the election results that deviate most from the

average in the

Reich

—both below and above the average (Jung 1995, 50–

71, 120; Jung 1998, 85). The benefit of such an analysis is already apparent

for 1933 and 1934 at the level of the

Reichstag

constituency,28 and is even more evident at district and local level: Hamburg and Berlin deviate the

most below the average in the

Reich

as a whole, by minus 10–11 per cent of votes on average.

——————

27 For the results at local level in Schleswig-Holstein, see www.akens.org/akens/texte-

/diverses/wahldaten/index.html (accessed on January 2, 2011).

28 My own calculations according to statistics of the German

Reich

(1935, 8, 45-47); ibid.

(1936, 37, 52ff.); ibid. (1939, 8, 56); statistical report on Hamburg (1934, 96); from Hamburg’s economy and administration (1934, 138).

268

F R A N K O M L A N D

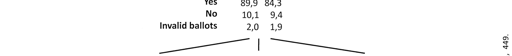

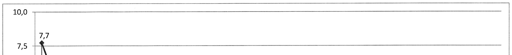

Figure 4: Results of positive votes above/below the average vote across Germany (Polls

November 1933 and August 1934) (Source: Frank Omland, 2011)

Of the cities, Lübeck (-15 per cent), the former Communist stronghold of

Lägerdorf (-13 per cent), and Harrislee near Flensburg (-19 per cent),

which was dominated by a Danish minority, are worth mentioning. If we

consider the results at the local and polling-station level, the extent of the

dissent becomes even more apparent, as the following graph for 1934

shows. From 1933 to 1938, Schleswig-Holstein, after the cities of Ham-

burg, Berlin and the region around Potsdam, always remained one of the

constituencies with relatively weak results for the Nazi regime. Similarly to

other regions with a high level of dissent, the no-votes registered here

came from former adherents of the Communists and Social democrats. An

analysis of the election results confirms this correlation: this is the case for the two cities of Altona and (to a lesser extent) Kiel, for the predominantly

industrial areas surrounding Hamburg and Lübeck, and also for Harrislee

and Lägerdorf. In 1933, Lübeck delivered the worst election result of all

for the NSDAP (71.6 per cent / 71.9 per cent) and was also one of the

main areas of dissent in 1934 (Omland 2006a, 154; 2008, 57–88; 2007, 29–

39; 2006b, 162–68). If we also consider the

Reichstag

election of March

1936, two assumptions are evident: first, it was easier to vote “no” in

towns and cities. Second, there remained between 1933 and 1938 in certain