Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love (21 page)

Read Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love Online

Authors: Giovanni Frazzetto

Tags: #Medical, #Neurology, #Psychology, #Emotions, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience

In the fifth century

BC

an illustrious visitor reached these shores on a trip from Athens. This was Hippocrates, the renowned physician who is considered to be the founding father of medicine and who surely knew how to cure a bout of sadness.

If today grief, sadness and depression are articulated in terms of neurotransmitters and their imbalance in the brain, back then, they were the outcome of a different kind of imbalance. Hippocrates understood moods and behaviour in terms of

humours

. Humour is a word of Greek origin literally meaning fluid. The general idea was that inside our bodies streamed a combination of four fluids, each with different properties, that worked to make up our health, both physical and mental.

46

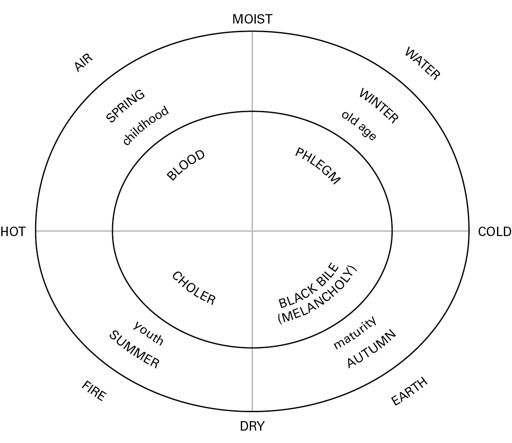

These four humours were phlegm, blood, yellow bile (or choler) and black bile (or melancholy). Where did they originate? Descendants of the universal cosmic elements – water, air, fire and earth, respectively – the humours were believed to be some side-product of the digestive operations in the stomach, processed in the liver and further refined in the bloodstream, and bathing all parts of the body, including the brain. Hippocrates granted the brain a primary role in determining health, modulating sensations, thought and emotion:

. . . the source of our pleasure, merriment, laughter and amusement, as of our grief, pain, anxiety and tears, is none other than the brain. It is specially the organ which enables us to think, see and hear, and to distinguish the ugly and the beautiful, the bad and the good, pleasant and unpleasant . . . it is the brain too which is the seat of madness and delirium, of the fears and frights which assail us, often by night, but sometimes even by day.

47

The exact appearance of the humours was not discernible, but they were to be found within visible fluids and discharges of the body. The humour blood was indeed part of the blood circulating in arteries and veins. Phlegm was present in the mucus of a runny nose and in tears. Choler hid in pus and vomit. Black bile was posited to be part of clotted blood or dark vomit. For Hippocrates, each person had their own composition of humours and the occurrence of illness was a disruption, an alteration of his or her humoral balance. Hence, treatment consisted in remedies that attempted to restore such balance and permit a return to the original equilibrium, for wherever there was balance, there was health. The degree of concentration of the respective humours and their proportions in a person’s internal blend were held responsible for the behaviour, temperament and mood that person manifested. Roughly speaking, an excess of phlegm made a person phlegmatic and peaceful. Too much choler caused irascibility. A glut of blood made people sanguine, that is upbeat and positive. An excess of black bile guaranteed the onset of melancholy.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the humours is that they were purported to be in constant dialogue with and a reflection of the external world. The internal microcosm of the body mirrored the external macrocosm and order of the universe. Hippocrates made the humours match the course of seasons and stages of life. Thus blood corresponded to spring and childhood, choler to summer and youth, black bile to a melancholic autumn and to maturity and phlegm to winter and old age. An individual’s humours were sensitive to the environment. External temperature and the seasons influenced the humoral composition. Heat and cold and the consequent conditions of dryness and moistness affected the overall balance of the humours and therefore the resulting mood. So, for instance, it was normal to feel hot and dry and be full of choler in the summer or have an excess of phlegm in the winter, which is cold and moist (Fig. 12). Hippocrates specifies how these imbalances affect the brain:

Fig. 12 Schematic view of the four humours and their correspondence to the four elements, seasons and phases of life (diagram adapted from Arikha, 2007)

The brain may be attacked both by phlegm and by bile and the two types of disorder which result may be distinguished thus: those whose madness results from phlegm are quiet and neither shout nor make a disturbance; those whose madness results from bile shout, play tricks and will not keep still but are always up to some mischief.

48

Since it was the heat of digestive processes in the stomach that was responsible for producing the humours they were also sensitive and responsive to a person’s diet.

Leaning on the authority of Hippocrates, the humours survived as a valid theory for over a thousand years and were relayed from healers to philosophers to doctors at least until the Enlightenment, flourishing among Roman physicians, in Arabic medicine, and in European medicine during the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Within the humoral framework, grief and sadness belonged to the condition of melancholy, and were, therefore, caused by a glut of black bile. Such excess produced symptoms such as despondency, dejection, tendency to suicide, aversion to food and sleeplessness – a list very similar to the criteria for a contemporary diagnosis of depression and to the symptoms of former versions of depressive illness, such as Freud’s melancholia. Some of the ancient medical treatises specifically talk about grief as an emotional reaction provoked by external events such as the separation from a loved one.

49

In general, such events caused an individual’s internal vital heat to subside. The treatises offered specific prescriptions and therapeutic recommendations including bodily regimens that ranged from physical exercise to particular food ingredients. The most important recommendation was to keep the body warm, to restore the heat and fight the cold dryness of the black bile, for instance by taking regular lukewarm baths. But there was also specific food advice. A melancholic was better off with a diet that included lettuce, eggs, fish and ripe fruit. He or she should avoid acidic foods, such as vinegar. The ideal day of a melancholic person would include a routine of walks, exercise, massages with violet oil, as well as sessions of music, poetry and recitals of stories or tales from the lives of sages.

50

Nowadays the ancient theory of the humours is considered inadequate to address the variations of mood and behaviour we ride in our lives. Nevertheless, today’s neurotransmitters and electric impulses are simply what humours used to be thousands of years ago. What the legacy of the humoral theory and the historical recurrence of the melancholic type do is remind us of the fact that the emotions of sadness, grief and melancholy have always existed. Depression, prolonged grief disorder and melancholy are permutations of the same emotion that have just been understood in different terms. I am not saying that we should embrace the humoral theory, nor that we should abandon neuroscientific research into the molecular basis of sadness. However, given some of the problems in the current system of diagnosis, the diversity of symptoms and underlying biological factors within a psychiatric condition, the multiplicity of its possible causes, not to mention the uncertainty about how effective contemporary treatments may be, there is room for a broader approach in treating patients. Especially those who are suffering from grief. Even though Hippocrates considered the brain to be an important centre for an individual’s emotions and tempers, his treatments were intended for the whole body and valued the uniqueness of each ailment in every patient.

An editorial in a recent edition of the

Lancet

, in an impassioned plea against the category of PGD and the risk of over-diagnosis and over-medication, stated that doctors facing the treatment of bereaved people ‘would do better to offer time, compassion, remembrance and empathy’ rather than the more advanced and synthetic therapeutic options that have come to the fore through the swift development of psychopharmacology.

51

This is not far removed from more ancient medical remedies and would conform to one of Hippocrates’s tenets in the practice of medicine, which was to ‘do no harm’ to patients.

Coda

‘The cure for anything is in salt water: sweat, tears or the sea,’ wrote Karen Blixen, in

The Deluge at Norderney

(under the pseudonym of Isak Dinesen). There is reassurance to be gained from this statement. We earn reward for every effort exerted. We feel better after the liberating action of a good cry. We can draw strength from the capacious calmness of the sea.

Gazing at the sea is a nurturing activity. Whenever I come to Sicily to visit my grandmother and return to the places where I spent all my summers as a child, I regain comfort and energy. I travel south to the very tip of the island to marvel at the horizon, planning my journey so that I arrive at sunset. When as a child I learnt the basics of geography, and about the movements of the earth, the moon and the universe, I found it simply magic that the sun, which on the east coast always rose from the sea and disappeared down behind the hills, could set over the sea if I just walked around the tip of the island towards the west – one of the advantages of living on an island. I wanted to come here every day because it felt as if I was turning the world upside down, and I rejoiced in the ritual and in the change of perspective.

Sunsets are hypnotic and have always been especially conducive to the melancholic mood. Melancholy assumes its most agreeable form at dusk. It belongs to the evening. Light is a brush, gently painting everything with a crepuscular tint. Somebody said looking west is like searching for immortality. When I stare into the depth of the horizon, I am reminded of my granddad and I look for the wake of his boat. The intrinsic and most vigorous, wicked quality of death is its irreversibility. Like candles, life burns in one direction only, until there is nothing left.

There is a poem by Robert Pinsky I found at a friend’s house.

52

It goes like this:

You can’t say nobody ever really dies: of course they do . . .

But the odd thing is, the person still makes a shape distinct and present in mind

As an object in the hand. The presence in the absence: it isn’t comfort, it’s grief

Sadly, when my grandfather passed away, my grandmother lost the man who, when alive, was without any doubt the person best at giving her comfort whenever she was sad. Now she needs to make Granddad live again in her memory and, through those images, occupy empty spaces that are just too wide to be filled. And that is what I do too, with Granddad and with the other people I have lost.

5

Empathy: The Truth Behind the Curtains

Those who see any difference between soul and body have neither

OSCAR WILDE

So I wish you first a sense of theatre;

only those who love illusion

and know it will go far

W. H. AUDEN

T

he lights have slowly come down, as the bell rings for the third time.

‘Please take your seats, and remember to switch off your mobile phones,’ we hear from a kind recorded voice. ‘The show is about to start.’

Next you can only hear the noise of people moving in their seats to reach the most comfortable position and be prepared. A few whispers, the last hissing sounds before the show begins.

Everyone is holding their breath. Theatre is a ritual, one of birth and change. Each performance buds and arranges itself into something new every night, even though it is the same play.

I am here to see my friend Ben Crystal on stage. He is going to be Hamlet. Right now, he is probably waiting in the shadow of the wings. When I go to see Ben act, I always wonder what he is up to during the moments immediately before entering the first scene.

Is he pacing up and down impatiently? Is he wrestling with his memory or murmuring to himself the unruly song of a few knotty lines? Will he see me sitting in the second row?

If, for the audience, the start of a show marks the entry into a new dimension, for an actor stepping into the light must be a rite of passage, a crossing between entire worlds. Depending on Ben’s state of mind, that first step on the boards must feel one day like a feather, on another like a stone – and I wonder if the latter is more congenial for playing Hamlet. Melancholy is Hamlet’s quintessence, the source of both his craftiness and his misery. But in either case, entering the stage for Ben must be akin to throwing an anchor that will moor him to his element. Acting is his second nature.

When he emerges, everyone’s attention is directed at him. ‘A little more than kin, and less than kind’. The first line is crisp and reverberates far.