Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love (22 page)

Read Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love Online

Authors: Giovanni Frazzetto

Tags: #Medical, #Neurology, #Psychology, #Emotions, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience

A passage in the second act always grips me for its intensity, and boldly uncovers the true core of acting and theatre. Hamlet has learnt from the ghost of his dead father that he was killed by his brother Claudius, Hamlet’s uncle. Hamlet is bewildered. His grief is shot through with outrage and indignation. Hamlet aches. However, he is crushed by his own incapacity to exact revenge. Hamlet is arranging with a cast of players a performance of

The Murder of Gonzago

– with the addition of a few lines written by himself – to mirror the death of his father and test Claudius’s reaction to the play as proof of his guilt. He prompts one of the players to recite the speech of Hecuba mourning the death of her husband Priam, the King of Troy. The player’s impassioned delivery leaves Hamlet awestruck. How can an actor’s fictional emotions be so powerful and, by comparison, Hamlet’s real sorrow so vulnerable and defenceless?

What’s Hecuba to him, or he to Hecuba?

asks Hamlet. How is it possible that an actor only needs to imagine grief for his face to pale, his whole appearance to turn sombre, his eyes to shed tears and his voice to break? And all for Hecuba, a woman so distant in time and space? What would an actor do if he happened to have Hamlet’s reasons for grief? His feeling would be amplified, Hamlet suggests.

Yet Hamlet can’t seem to master his own emotions sufficiently to avenge the death of his father.

As I listen to the man in front of me lament his solitary feebleness, a singular, reliable and generous relay of sentiments takes place. Embodied in Ben’s minutiae of enactment, carried and delivered word for word through the acrobatics of Ben’s voice, that song of desperation travels across the footlights and invades me. Even if I am sitting motionless, something stirs inside me. I feel the blow. By one degree of separation, I at once participate in Hecuba, the player and Hamlet’s grief.

Imperceptibly, I stop seeing Ben and see only the Danish Prince.

In those hypnotic instants, I forget where I am. It is in that state of reverie that I wish those moments might last for ever, that a performance might never end.

A kind of magic

Anyone still maintaining dualist notions of the separation of mind and body is bound to forsake them in front of a stage, when the velvet curtains are drawn back. Watching a theatrical performance one recognizes the harmonious integration of body, intellect and whatever it is that we call consciousness and feelings.

In the concluding pages of his treatise

The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals

, Darwin acknowledged the power of theatre to evoke emotions: ‘even the simulation of an emotion tends to arouse it in our minds’.

1

To back up this assertion, he recalls Hamlet’s awe at the player’s ability to manufacture emotions.

Darwin’s detailed and vivid descriptions of facial expressions and their corresponding emotions could well constitute a rich resource for actors. Quotes from Shakespeare’s plays are used by Darwin as supporting proofs of his own observations. He praises the Bard as being an ‘excellent judge’ of emotions, and as a man with ‘wonderful knowledge of the human mind’. When Darwin describes the emotion of fear, he explicitly cites Brutus’s reaction to seeing the ghost of Caesar: ‘Art thou some god, some angel, or some devil, that mak’st my blood cold and my hair to stare?’

2

In search of support for his observations on rage, Darwin quotes Henry V’s battle speech to his soldiers, when he urges them to ‘stiffen the sinews and summon up the blood . . . set the teeth and stretch the nostril wide’.

3

When writing about shrugging, he mentions Shylock from

The Merchant of Venice

.

4

Theatre is definitely a prism through which light is scattered in a whole rainbow of emotions.

But how does theatre cast its magic spell? How can a story embodied into stage action have the power to deeply move an audience and stir emotions?

In the darkness of a performance, we participate in an active emotional exchange. We are launched into a story and the plight of its protagonists. We experience the vicissitudes of fictional characters with unique desires and intentions, the realization of which is often conflicted. By doing that, we shed light on our own. By watching on stage a snapshot of the lives of others, we are watching what could happen to us and we are learning about our own world.

5

This gives us the chance to

empathize

with the characters and grasp what they are going through.

The word ‘empathy’ made its first appearance in the English language in 1909, as a translation of the German ‘

Einfühlung

’, in turn introduced by the German philosopher Robert Vischer, which means ‘feeling into’.

6

Vischer first talked about

Einfühlung

referring to the field of psychology of aesthetic experience to remark how an observer perceives a work of art he or she contemplates. In front of a painting, a sculpture or another type of artwork, a viewer empathizes, or fuses, with it – just as I was absorbed into Caravaggio’s painting at the gallery in Rome.

7

Over time, the term empathy was used not only to explain our relationship to inanimate objects, but also to describe how we can instinctively understand other people’s mental states.

Empathy lets all kinds of emotions reverberate amongst us. It is the capacity to recognize and identify with what another person is thinking or feeling, and to

react

with a comparable emotional state.

8

Empathy is the backbone of our social life. Whether in thoughts or acts, it intrinsically demands an interaction with others. It has the power to spread joy, euphoria or laughter, but it also helps mitigate difficult circumstances – for instance, alleviating negative emotions. Anxiety, guilt, sadness, despair are somewhat eased if shared with others. Empathy is like an invisible bond with the power to unite us to other human beings and blur the dividing line between ourselves and them – as in the case of me and Hamlet during Ben’s performance.

In this chapter I am going to use theatre as a vehicle to understand empathy and how emotions are perceived and communicated. I will first introduce the brain mechanisms that scientists believe mediate empathic reactions and how they were discovered. Then I will explore the dynamics of the actor–audience relationship and the techniques actors employ to charm audiences with their emotions. Lastly, I will also talk about how the brain distinguishes between reality and fiction and what happens in the brain during moments of absorption into fiction, those instants when we are magically transported into the world of imaginary characters.

9

A mirror for our emotions

The Spanish neuroscientist Santiago Ramon y Cajal (1852–1934) wrote: ‘Human brains, like desert palms, pollinate at a distance.’

10

It is fascinating that he should be the author of such an affirmation, because his work paved the way for the understanding of how neuronal connections are established. Thanks to a silver staining technique developed by the Italian scientist Camillo Golgi, Cajal demonstrated that the nervous system is not an uninterrupted bundle of neurons wound around itself, as was generally believed at that time, but rather was composed of neuronal cells as separate units coming into contact through their ramifications. And we definitely need those neuronal contacts in order to empathize.

A new and attractive framework for the understanding of empathy emerged with the discovery of ‘mirror neurons’, cells that have revolutionized how we regard our emotional connections with others.

11

The discovery was as important and sensational as it was serendipitous. Back in the 1980s in a laboratory in the Italian city of Parma, Giacomo Rizzolatti, Vittorio Gallese and colleagues were investigating which brain areas were involved in the execution of movements. They noticed that a group of neurons in a region of macaque monkeys’ premotor cortex, called area F5, fired when the monkeys performed a simple action such as reaching for a bite or grabbing a peanut. But F5 neurons were activated only if the movement involved an interaction between the agent of the movement and an object, and not if the movement had no specific goal or intention. Simply moving the arm with no goal was not enough for the neurons to scream their involvement in the detection instruments.

To deepen their findings, in the mid 1990s, the researchers then implanted electrodes in the monkeys’ brains to record activity from

individual

motor neurons in area F5 while they gave the monkeys different objects to grasp. Here is where they faced a huge surprise. The moment they picked an object to hand on to the monkeys, the electrodes signalled some neuronal activity. To the researchers’ amazement, the recorded activity came from exactly the same neurons that would also fire when the monkeys picked the same object themselves. Basically, the neuronal activity of observing an action

mirrored

the activity of performing the same action.

12

These results were extremely thrilling because until then scientists had thought that the area F5 was involved exclusively in motor functions. Instead, the newly discovered mirror neurons displayed motor

and

perception capacities. When the monkey watched an action, even though it did not move a muscle to reproduce it, its mirror motor-perceptive system was activated as if the monkey were executing what it saw. In other words, the brain simulated action.

13

After these exciting discoveries in monkeys, everybody asked: do humans also have mirror neurons?

Applying electrodes deep into the brain of a person in search of single neuronal activity is not a feasible procedure. What you can easily do in humans is to use less invasive techniques such as fMRI. fMRI does not detect the electrical activity of single neurons, but the blood flow in the whole brain, so fMRI data would reveal areas that are active during both the observation and the execution of actions and

might

, therefore, contain neurons with mirroring functions. That is why in humans you cautiously talk about ‘mirror-neuron systems’ rather than single mirror neurons.

One of the first studies of mirror neurons in humans asked participants to watch experimenters make finger movements and then imitate those same movements. The results identified two cortical areas with mirroring functions.

14

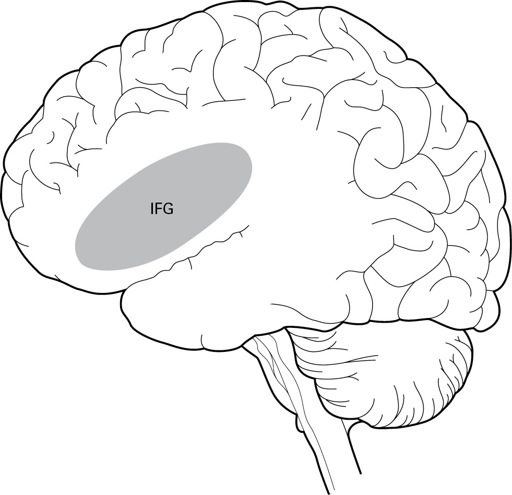

One, located more towards the front of the brain, includes the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) (Fig. 13) and the adjacent ventral premotor cortex (PMC). Another, located further back, is the inferior parietal lobule (IPL), which can be considered the equivalent of the monkeys’ area F5.

Fig. 13 Inferior frontal gyrus

The IFG is located within Broca’s area, which is the brain’s main language area. This suggests that the mirror-neuron system may have been an evolutionary precursor of neural mechanisms for language. Speaking of evolution, it seems that the IFG may have evolved to be the common denominator underlying empathetic understanding across different emotions. A study testing which brain regions responded specifically to four basic emotions – happiness, anger, disgust and sadness – revealed that the degree of activation in the IFG correlated positively with the levels of empathy shown towards all of them.

15

So, mirror neurons basically give us a second, more intuitive pair of eyes that shortcut the comprehension of the actions we witness. They allow us to apprehend an action we observe by making us simulate it in the brain. We

internally

know what someone else is doing.

This idea soon made researchers believe that the role of mirror neurons within the context of perceiving and simulating a simple action was only a tiny part of a more evolved mirroring system we use to empathize and understand each other’s emotions. It only had to be uncovered! Emotions are contagious. How many times do we find ourselves cringing, smiling, or even laughing if someone else does it in our presence and before our eyes? Not only at the theatre, but in all kinds of daily social interactions.

Indeed, one of the first studies that investigated the empathic role of mirror neurons in humans adopted a paradigm of observation and imitation of facial emotional expressions.

16

The study consisted in letting participants first observe and then imitate facial expressions of the six primary emotions – joy, sadness, anger, surprise, disgust and fear. The mirroring network responded during both actions, especially during imitation. In addition, the amygdala was also involved. This revealed the link between the human mirroring system and the limbic brain. Anatomically, this link is achieved via a region in the brain called the

insula

, which was also activated during the procedure.