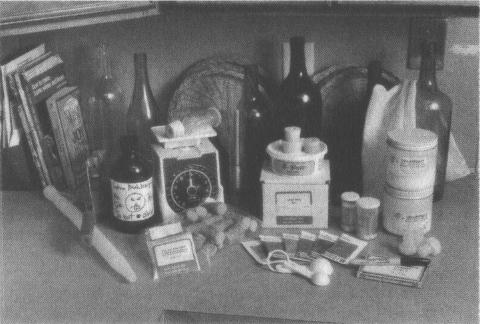

Joy of Home Wine Making (8 page)

Read Joy of Home Wine Making Online

Authors: Terry A. Garey

Tags: #Cooking, #Wine & Spirits, #Beverages, #General

Mother Nature loves us. But she loves mold and bacteria just as much. It’s all the same to her!

ALWAYS clean up as soon as you can, and before you use your equipment again, sanitize it once more. Be picky. It pays off. I’ve never (she said, knocking on wood) had a batch go sour on me.

S

ECONDARY

F

ERMENTERS

After two or three weeks of fermenting on the fruit, you will need to rack the wine into a secondary fermenter, which is either one or more one-gallon glass jugs or a five-gallon carboy. Use the five-gallon carboy only if you are going to fill it with five gallons of wine. During secondary fermentation, you want to avoid as much contact with air as you can.

If you planned to make three gallons of wine and have miscalculated and made, say, two and a half gallons of wine, use two gallon jugs and a half-gallon wine bottle. Or if you like, you can use a third gallon jug and top it up with some frozen juice and sugar and water, keeping in mind the acid content of what you are working with. If it is a low-acid juice (there will be a discussion of this later, don’t worry), you will need to add some acid or lemon juice. The third gallon will throw a heavier deposit and it will need to be racked earlier.

Over the years I have found that it is better to keep five gallons of the same wine in a five-gallon carboy than in five one-gallon jugs. I’m not sure why this is, but the wine comes out better. It could also be that a large container is less susceptible to temperature fluctuations. Except for the weight, this approach is less fussy to rack and bottle, and less wine is wasted during racking.

I don’t recommend keeping wine in the primary fermenter for more than a couple of weeks. I’ve done it, but I still don’t think it’s a good idea—too much risk of oxidation with all that exposed surface.

I’ve never used a plastic secondary fermenter, though I know collapsible plastic jugs are sold. In my humble opinion there is too much risk of strange flavors from the plastic, and contamination from an unseen scratch or imperfection.

Everything I have read has advised against using plastic as a secondary fermenter.

You are going to want to invest in a few five-gallon glass carboys almost immediately. Wine shops carry them new and used. Used, they run about twelve to fifteen dollars; new, they can cost up to twenty dollars. Sometimes you can luck out and find a used one at a thrift shop, or buy one from someone who is moving. Always clean a new or used carboy before you use it. Check for nicks around the top, and check the bottom for chips. Don’t buy a carboy that has chips, nicks, or cracks. It isn’t worth it.

Occasionally you will find a three-gallon, or even a two-gallon, carboy. Buy it. These are nice for smaller batches. The more sizes you have, the better off you are. Some shops sell special handles for carboys, to make it easier to haul them around when they are full.

A full carboy weighs a LOT! Fifty pounds or more of dead weight! Always handle them with care and respect. My partner and I were lifting one to empty out the sanitizing water one day and forgot to pad the edge of the laundry tub. The vessel shattered. Luckily we were not hurt, but the shards of glass were everywhere.

Many carboys fit snugly into some common sizes of plastic milk crates. These make handling the heavy carboys easier and safer. You can buy them in department stores and stores that specialize in closets and storage. Make sure that you buy sturdy ones, not the flimsy kind one finds at dollar stores. They have to hold more than fifty pounds of dead weight without the bottom falling out.

C

ARBOY AND

B

OTTLE

B

RUSHES

The carboy brush is curved and has a long handle. Get one, they’re cheap. Ditto for bottle brushes.

A

IR

L

OCKS

Air locks are inexpensive little gadgets with a stem that fits into a hole in the rubber bung, with which you will be sealing your primary and secondary fermenters. You fill the air locks about halfway with metabisulphate and water or some other sterile solution, drop the little cap over the hollow central stem, and put a little pill bottle cap over that. The pill bottle cap has a tiny hole that lets out the carbon dioxide that filters up from the fermenting yeast through the water in the lock but prevents the water in the lock from evaporating too quickly. As long as they have water in them, air locks will also keep out air, flies, and dust. Very simple; very effective. Long after the really active fermentation the wine needs to be protected until the final racking and bottling.

Some people fill the air lock with vodka, though I should think this would evaporate at a much higher rate than water. I use a metabisulfite/water solution. Sometimes plain water will develop

mold, and you don’t want that! You can keep a jug safe from harm for well over a year if you use an air lock and keep the solution at the proper level.

Get lots of air locks. I prefer the plastic multipart kind, which are easier to keep clean and harder to break. Get bungs to go with them to fit your various gallon jugs and your carboys, including a few small ones to go on your primary fermenter top and the occasional single bottle of “topping up” wine left over from a bigger batch.

When you finish bottling a batch of wine, check your air locks for mold and cracks. Sanitize the air locks by soaking them in our standard solution of water and bleach. Don’t boil them; they melt. Leave them on a towel to dry, and sanitize them again before you use them.

It is false economy to use damaged air locks. In a pinch you can use the old plastic wrap and rubber band method, but I wouldn’t for the long run, unless you are going away from your winery for an extended period and can’t find someone to check your air locks for water once a month.

Replace your air locks when damaged, or every two or three years on general principle. There isn’t that much plastic to them. Children who are old enough not to put them in their mouths like to play with them, using them for everything from rockets to doll cups.

B

UNGS

Bungs are cylindrical rubber plugs that fit snuggly into the openings of jugs, carboys, and barrels. They come in many sizes, from barely half an inch across which fits the average hole in the lid of a primary fermenter to huge ones for barrels. Most come with a hole drilled through the middle to accommodate the stem of an air lock, though you can obtain solid ones. Bungs are an inexpensive but important partner to the air lock.

When you are fitting a bung to a jug, remember that putting the stem of the air lock in it will firm up the bung a bit. I have a lot of jugs that fit the 7.5 and the 8 bung size; can I tell by eye which is which? Surely you jest. Some carboys have smaller openings than one-gallon jugs. Keep a variety of sizes around, as well as the tiny size for primary fermenters and individual wine bottles.

You might want to get some bungs without holes to fit gallon jugs. This way you can store a finished wine that you will be using in large quantities (for parties, etc.) without having to bottle so much. Wines can keep for two or more years this way.

Check the rubber bungs periodically. Keep them clean. Bleach isn’t good for rubber, and metabisulphite isn’t either, so don’t soak them, though you can rinse them off in hot, hot water (not boiling!) and dunk them in and out of a sanitizing solution. Then let them dry and keep them in a plastic bag until you need them again.

Just before you are going to use your bungs, rinse them off in hot water, and then in sanitizer again, and keep them there for a few minutes until you fit them with an air lock and the whole thing goes into the neck or opening of the fermenter. Don’t absent-mindedly set them down on a dirty counter, on the edge of the washer, or on the garbage pail lid.

Remember, when the bung goes into the neck of the jug, its

bare little bottom will be hovering above your precious wine; if you slop the wine while carrying it, or the wine froths up in an excess of enthusiasm (which happens during primary fermentation, mostly), nasty things could get into your wine and ruin it. So keep the bungs clean!

When a rubber bung starts looking tatty, or loses its elasticity, get rid of it. They are very cheap, and they biodegrade. They make a fine hockey puck if you know some kids who could use a few.

N

YLON

S

TRAINING

B

AGS

In the old days, fruit was cut up or crushed and tossed into the primary fermenter and had to be strained out later, which was a very messy process. Today most home winemakers use a nylon straining bag to contain the fruit during the primary fermentation. They look like the laundry bags you can buy for washing delicate items in a washing machine, but with a much finer mesh.

Nylon straining bags come in small and large sizes. They are strong, inexpensive, easy to sanitize, and they last a long time. You can buy them at your wine supply store or by mail order. If you have a sewing machine or serger, you can make your own. Be sure you use fine, flexible nylon cloth if you make your own. Do not use stiff nylon netting or polyester.

Not only do nylon straining bags make removing the fruit or vegetables easier, but they also prevent clogs later on when racking. There’s nothing like a stuck cherry pit or apple chunk to ruin a racking tube.

To sanitize, either boil or soak in sulphite or bleach solution.

To use, tie the bags closed with kitchen string that has been boiled along with the bag or soaked in sulphite solution. After the fruit has fermented in the primary container, merely lift the bag out of the fermenting wine and let it drip a bit, then get it to the sink without dripping everything all over the floor. I use a big pot lid or tray to accomplish this.

Fermented fruit is not a pretty sight when emerging from the bag, nor does it have a pleasant smell. Carefully cut the string (be sure you don’t nick the bag) and dump the fruit dregs into the compost bucket or into a strong discardable plastic bag. As soon as you can, rinse the nylon bag out with hot water, get rid of all

the fruit bits, and turn it inside out and back again to get rid of the crud. Wash in hot soapy water, and bleach to whiten it. Rinse the bag in hot water and hang it up to dry to be ready for the next time you need it.

S

IPHON AND

R

ACKING

T

UBE

A siphon is merely a long tube made of transparent flexible plastic. A racking tube is a piece of rigid transparent plastic that attaches to the siphoning tube. One kind of racking tube is open on one end and closed on the other, with a couple of holes drilled through about an inch above the closure. Another kind has a small foot of plastic, which fits over the bottom end to let the wine be drawn in when you rack but keeps the tube out of the sediment.

The racking tube is usually two to three feet long, for either one-gallon jugs or five-gallon carboys.

When you gently introduce the racking tube into the wine you want to rack, keeping the bottom of the rigid tube on the bottom of the jug, it sucks in the mostly clear wine through the little holes above the

lees

, or sediment at the bottom, leaving the gunk at the bottom of the vessel.

Of course, if you stick it in there and swish it around, the lees get stirred up and you’ve lost the advantage and will have to wait for the wine to settle down again. Toward the end, you can gently tip the jug to keep getting clear wine, before the sediment slips down all the way and starts to cloud.

Having two tubes around is a good idea, in case one cracks. You can get them in different sizes, as well.

Keeping the tubes clean can be tricky, but if you are consistent about it, you’ll be OK. Always rinse your siphoning tube right after using it, letting LOTS of fresh hot water flow through every part of it. Then carefully let some sanitizing solution run through it, let that run out, and hang it up to dry.

Store your tube in a clean plastic bag to keep it from getting dusty or from having flies play in it like a hamster habitat.

Before using it to rack, soak it in a dishpan of sanitizing solution, making sure that no air is in it and that it soaks in the solution on every surface INSIDE and OUT. Take the tube out and rinse it briefly with fresh hot water just before you use it. Never let it touch a dirty surface while you are using it. This can

seem complicated and it can get tricky, but with practice it is easily done.

If I am bottling several batches, I carefully insert both ends of the tube into the jug I’ve just siphoned off while I get the next jug ready, because I know the inside of the bottle is pretty clean, except for leftover wine and lees. It isn’t necessary to clean the siphon tube between wines as long as the wines themselves are sound and you are moving quickly. Nothing awful is likely to happen in those five or ten minutes.