Joyland (3 page)

“Oh man!”

“She doesn’t get it,” J.P. said with a mocking glance at Tammy.

“Of course not, she’s eleven!” Chris sucker-punched J.P. and J.P. doubled over. “Don’t talk that way around my sister.”

“Yeah, well, you laughed.” J.P. faked a jab.

“Tell me, Chris.”

“No way.”

J.P. leaned down, cupped fingers confidentially around Tammy’s ear. She arched into his hand.

“Tell me,” she said, this time to J.P.

J.P.’s voice was husky as he hissed, “It has to do with s-e-”

“Don’t!” Chris yelled, ineffectual as Tammy usually was. J.P. held him off with one elbow.

J.P. threw his head back and yelled: “S-E-X!” The whole arcade swivelled slowly, looked over with disinterest — the kind of gradual, obligatory head turn Tammy’s mother did whenever she yelled, “Mom, look! Look!”

“They say that incest is best,” the pinstripe girl called over.

“You would know!” someone yelled back at her.

“Yeah, your mother showed me.”

They all turned back to their games.

That night, as Tammy ran home, the concrete blurred beneath her running shoes. White flecks flashed like constellations embedded in the dark asphalt. A universe spun away under her footsteps. Spirograph pictures passed beyond her recognition. The starburst on the jukebox panel. Things she would never see again. She closed her eyes and imagined the air pushing past as J.P.’s breath when he whispered

“s-e-x.”

Closed, the world around her became bits. Its sounds and its smells. The cut grass of the Scotts’ lawn. The indent of the sewer that clanked when she ran over it. The lopsided lurching of running blind. Open, Tammy took in the world and stepped over the curb, across the grass clippings (which stayed on her shoes). She continued on the sidewalk — over squares that had been newly paved — a pancake paleness in comparison to the street. Her calves jolted with every step. An X mark had been made with a fingernail overtop of a mosquito bite to stop it from itching. Short thin hairs stuck out over the elastic of tube socks. All down the street, houses shimmered lit eyes, windows still open, only the hum of an air conditioner or two breaking the pinging that lingered in Tammy’s head.

She stood in her driveway, looking up at the Little Dipper. A line of crabs inched its way across the night sky. She locked her fingers into the shape of a pistol. Raising it above her head, she watched the streetlight throw her shadow into the silhouette of a Charlie’s Angel. Tammy angled her body away from the house, where her mother had just flipped on the porch lamp.

“Pow,”

Tammy whispered.

“Pow,”

and she shot at the stars before she heard the door open, and her mother calling her in.

LEVEL 2:

FROGGER

PLAYER 1

After Joyland closed, the youth of South Wakefield had nothing to do but concoct ways to kill each other.

Until that point, the world Christopher Lane had lived in held a faint glow, like a vending machine at the end of a dark hall, a neon sign blinking OPEN again and again. Fear was the size of a fist, and the town where Chris lived was little more than the smell of manure and gasoline, the sound of breaking glass and midnight factory whistles, a series of houses he had or hadn’t been inside. Permanent items disappeared in an afternoon, and Chris would later wonder if they had ever existed. A lost street-hockey ball, its lonely green fuzz languishing to grey in a thick lilac bush in some backyard beyond penetration. An incarcerated swingset whose legs had always kicked off the grass with their enthusiasm. The dog who couldn’t stop humping, though Chris didn’t even know what that was then, the mangy beast seeming only excitable and overly affectionate toward him until the older kids clued him in, pausing their whoops for a minimal parcelling of information. Chris shook his leg and the dog wrapped its paws Chinese-finger-trap tight. Chris shook, then kicked, the dog’s butt scuttling across the cement. These other kids moved out of the neighbourhood gradually, like cranberries falling off a nostalgic half-dried Christmas string — two and the thing was drooping, four and the neighbourhood seemed on the verge of decay. A set of sisters too old to bother about. A pair of grape-juice-lipped brothers, one with a motorized go-kart, the other with the unnatural ability to recite the entire alphabet while belching. Chris and Tammy stood on the curb and sang, “Na-na-na-na, Na-na-na-na, Hey Hey, Goodbye!”

But the Lane house didn’t change. Nothing changed except the television commercials, and the things Chris wanted. A bitty grey woman growled,

Where’s the Beef?

A long-eared cartoon bounced between two blond child actors, his shape stitched immaculately to the screen somehow, above or behind their blood-and-bone figures, the point nothing more than brightly coloured breakfast cereal:

Silly Rabbit, Trix Are for Kids!

The ongoing inanimate argument between solid, dependable Butter and the sneaky-lipped dish of

Parkay.

A bear knocked on the door, proferred a cereal bowl:

More Malt-O-Meal Please!

Meanwhile, in other corners of the household, a ten-year-old set of toenail scissors stood guard, in their usual station on the second shelf of the medicine cabinet. They donated their opaque moon-shaped testimony to the Lanes’ normalcy.

Like all children, Chris felt his parents mysterious — their joint and sudden chorusing into songs he had never heard on the radio, their individual smells, the way they would fuse occasionally at the lips or fingertips as if drawing power from one another, recharging. His father’s accent lifted around the other kids’ parents and eventually cologne-faded from dense to faint, American twang settling into something flatter, something Canadian. Mr. Lane’s brown brow hid a machine of knowledge. Mrs. Lane’s polyester pants had the miraculous ability to turn into a folding chair where Chris could sit for hours. Days smeared under his palm like eraser guts (Pink Pearls and Pink Pets, Rub-A-Ways and Arrowheads, Unions, a bright green Magic Rub, the Sanford Speederase made in Malaysia, the godly Staedtler Mars Plastic); they blew away leaving only a faint grit. Chris seemed to age in three-year increments, passing from three to six (before three was thumbsucky and didn’t count), six to nine, nine to twelve, and twelve to fourteen, an age that, fittingly, broke the cycle. Running Creek Road was the world, and the world was big and small simultaneously, easily forgotten.

Joyland opened in the midst of the third trimester. Chris underwent a delivery, in reverse, leaving the outside world behind as he clamoured into the dark.

He found a just-across-the-street understanding of the opportunity for pleasure. The constant presence of temptation smoothly transformed into something less like sin and more like human experience. Holy mechanics comprised a system that could be predictable and random simultaneously. This was the world of the video game. In this universe there was no guilt, no darkness to the daylight. With twenty-five cents Chris experienced explosions of colour, the graphics on the screen somehow representative of all the beautiful, violent things he did not yet know.

He crossed this street again and again. The candy-coloured cars flew by him and he proceeded with minimal caution toward his destination, as if drawn by a homing instinct.

Joyland was located three blocks down from the one-level house where he lived with the people who had emerged into reliable unmysterious figures: Mom, Dad, and Tammy. South Wakefield lay like a plain white dot on a large dark screen — population 9,000, situated in Southern Ontario. As minute and unremarkable as a fly on a lily pad. Beyond Running Creek Road, there were six factories, five churches, four elementary schools, three sports stores, two arcades, one strip mall, and a movie theatre that had been turned into a “gentleman’s club.” Chris was fourteen years old and Joyland was the only place where he felt himself shine.

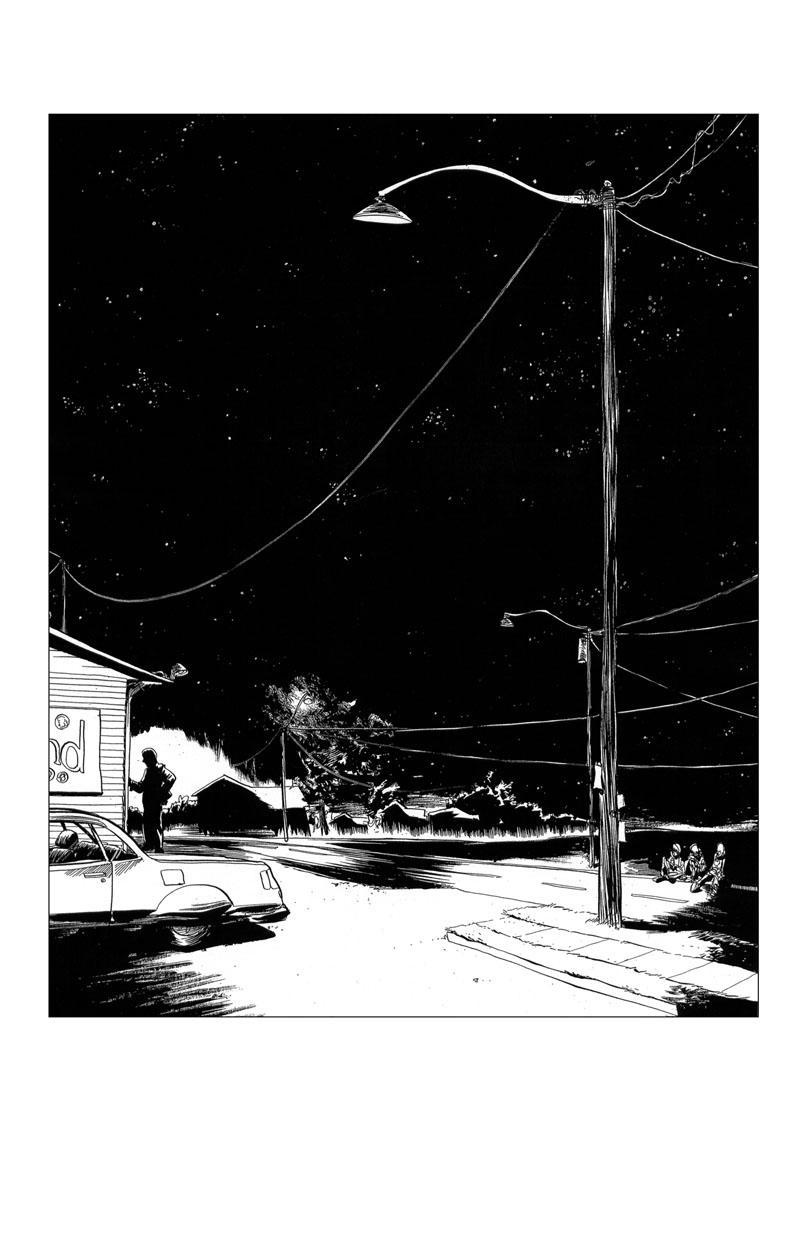

During the day, the road was like a fluorescent tube, sunlight thrown from it, blinding. A rumble of transports and supply trucks thrummed from one end to the other, heading on through, down into the States. At night, the hose of the highway lay silent, turned off. Only the occasional truck, trying to make some time, threw up grey dust in its wake. Joyland sat on the other side like a small black hole in the pocket of the night.

The stunt in the road hadn’t been Chris’s idea.

Tammy sent home long ago, J.P. and Chris sprawled on the curb opposite the arcade, leaning back on their hands, drinking grape pop. Over the course of the night, the misplaced patch of boys grew in the stretch of cement in front of the Twiss’s Gas ’n Go. In addition to Christopher Lane and John Paul Breton, gathered a standard post-Indian-Creek-Grammar-School group: David White, Kenny Keele, and Dean and Reuben Easter. Pinky Goodlowe had been too steamed to stay. He’d jumped on his BMX and ridden away, massive knees hitting the handlebars.

“Man! I dunno, we got this sort of, like, bottomless summer now. Eight whole weeks of nothin’. How many days of pure street hockey d’you think you can stand? In a row, I mean?” J.P. spoke specifically to Chris, the others oblivious to the gravity of the situation. Chuckling, David had pressed his crotch against a gas hose, pretending to pump the pump. Between his legs the nozzle hooked in — blank tin body and glass face — the machine reduced to the simplest notion of female, something entered.

Chris shook his head. “The crescent’s good for it, I guess.”

“Yeah, but my folks hate it. They’ll beat my ass.” J.P. stretched his legs out in front of him, bent slightly at the knees. “Straight days of hockey, draggin’ the freakin’ nets back and forth every time a car wants in or out. The neighbours’ll be over yellin’ at my mom before the week’s out. What else we got?”

“I don’t know.” Chris tilted his head back and let the last swig of pop ripple through his throat. “Swim, bike, TV, soccer, baseball, the usual . . .”

“Pffft. Boring, bo-ring.” J.P. squeezed his bicep, the muscle bulging up around a mosquito that had landed there. He watched its back end fill with blood. When it burst, J.P. wiped the residue off with two fingers and leaned over to rub them on Chris, who lurched up and away a few feet. J.P. reached round and rubbed them on the ass of his shorts.

“I don’t know why you do that. You still get the bite, ya know.” Chris scrambled back down, settled on the curb more upright.

“’Sfun,” J.P. shrugged.

David dropped to the curb beside them, followed by Kenny, Dean, and Reuben. Behind them, Johnny Davis had claimed a seat atop the mailbox in mute sixteen-year-old oblivion, with the exception of the odd fartish exhalation.

The side door to Joyland opened, rapping across the concrete night. They all stilled, watched Mrs. Rankin reach up to unhook the bells. In one hand she grasped the chip carousel from the counter, yellow plastic pouches still hanging from it. The other fist fumbled with the string of chimes, which warbled through the dusk with ecclesiastical melancholy, until Mr. Rankin appeared, a thick ring of keys hanging from his thumb. He reached up — the woman’s stubby white fingers still groping — and unjangled the bells with a click into his silent hand, the other closing the door and poking the lock.

They waddled to their truck to stash their things. She got in, sat staring out the windshield at the boys across St. Lawrence Street. She had trout-coloured eyes, visible even from that distance. Mr. Rankin returned to the door and fastened a heavy chain across its handle.

The boys sat with the final snap of the padlock clamping down on them. Mr. Rankin turned his back to the blotted black building and walked slowly to the vehicle, opened the door, and got in — no sudden movements — as if he could feel bullets in the boys’ gaze. The potato chip rack, shoved between them in the front seat, waved little cellophane wings, rotating when the truck reversed. A scatter of gravel. But before the headlights had disappeared down the highway, the boys had begun a eulogy, recounting their greatest Joyland moments.

Upon entering, there had always been a moment of disorientation. Although the arcade was at street level, it had small, raised windows like a basement, which gave it a watery underground aura. Walking out of daylight into the dim hull, the eyes always needed time to adjust. This second was a pure assault of sound. The noise of bells and bombs as they dropped. Of hearts beating and alien life forms detonated. Slowly, sight returned. A pulsing room came clear, streaking and glittering in the dark. Chris would begin scanning the place for the first available game.