Joyland (5 page)

“Did you come here to meet Dad?”

“I met him later.”

“So you came here to go to school?”

“No, I just came. Because.”

“You came and you lived here all by yourself?”

“Go play with your sister.”

Chris had seen the farmhouse, once, though it wasn’t more than forty kilometres away. However ambiguous the “couldn’t stand to stay” answer, it was, in itself, an admission of passion. His mother fled grave sadness, suitably outfitted with a Samsonite makeup case, and a Jackie O. coat with big buttons, clomping down the stairs of the bus like Marianne Faithfull off an airplane, desperately searching for something

far out

— desperate enough to drop out of school at seventeen and work in a factory for it. But neither Mrs. Lane nor Mr. Lane would admit to ever having used the phrase “far out.” They claimed to be too old by the time the ’60s hit though, using proper math, the answer did not compute.

Chris backtracked and dropped his parents into more traditional settings, occasionally Al’s Diner or the Bunkers’ living room. Once, when Chris had shown a brief interest in motorcycles, Mr. Lane had explained the row of old-fashioned bikes and scooters pictured in Chris’s library book. He casually tapped the ones different friends or acquaintances had owned.

“Gas tank in this model’s right here . . .”

tap, tap

“. . . meant guys were riding around with a hot tank of gas right between their legs.”

In the boy’s mind, Dad was soon outfitted

Sha-na-na

style and had owned each of the vehicles consecutively. When Vietnam hit, Chris’s father had crawled belly-down through mud in the middle of the night to get across the border to safety in Canada, the sky glowing eerily behind him as if the war were actually occurring within the U.S. instead of far overseas. In truth, Mr. Lane had arrived with a machinist’s qualifications. Canada needed cheap labour — non-union — and Nam had absolutely nothing to do with it.

In the lives of Chris’s parents, there were two things of utmost importance, so far as Chris could see: 1) which of them would drop the kids off; and 2) what they were going to eat for supper. There was also 3) money, but that was not discussed openly. In this way, Chris’s parents functioned as a distinct force, sharing the same concerns, their actions made with deliberate unity. Kentucky Fried versus the local fish & chips. It was a decision of enormous gravity.

At fourteen, this is what Chris knew of his mother and father: on Sundays his mother wore tan sweater vests and white blouses with big bows at the throat; his dad wore wide-collared shirts that had gone out years ago, stiff brown polyester slacks, and brown shoes; Mom smoked menthols; Dad, duMaurier; they sat in the same chairs every evening in front of the television; Mom preferred Dad to drive on any trip beyond town limits, or at night, but she was otherwise quite happy to run Tammy and Chris here or there; Dad was obsessed with weight, and Mrs. Lane had dwindled over the years; Chris’s father was, in most matters of consumption, frugal, yet every day, even in winter, ate a single scoop of chocolate ice cream after supper.

At age ten, Chris and Kenny Keele had finished off the carton one afternoon, promising Mrs. Lane they’d go to the store to buy more. They promptly forgot. After supper, Mr. Lane had gone to the freezer. He rummaged behind steam breath, face hidden by the open door. Clearing plates, Mrs. Lane didn’t say anything. Shut-door, Mr. Lane walked from the room without glancing at any of them. In the mudroom, he put on shoes (he never wore them in the house, though Mrs. Lane did). He removed coat from hook. The zipper toothed out a

pffft

that could be heard from the table. Leather gloves snapped softly over wrists. Tammy gaped all fish-eyed.

Mrs. Lane did not look at Chris at all. She turned a blast of water into the kitchen sink. Dad went out. The door closed with a civilized

foooom

behind him. Chris sat gazing down at the plastic lace cloth on the table. He traced taupe eyes on white plastic with his finger — no hole or height difference between the eyelet pattern and the rest of the cloth. His mother turned off the taps, and Chris knew there were wide, white letters ringed with blue, ringed with red, tight beneath her palms — faucets fashioned at the factory there in town. Sometimes, Chris imagined them, shipped all over the continent, ringing under the dirty hands of strangers, the steel name of his hometown brand emblazoned under their palms, as close as he could get to being somewhere else.

Tammy continued to stare at Chris. He stood up and pushed his chair in hard so that its back slat landed a wooden slap against the table edge.

“So?” he railed, arm shooting out vaguely at Tammy as if it weren’t attached to his body. He swaggered out of the room. By the time he’d reached the hallway to their rooms, that swagger was a half-sprint. He chunk-clunk-slammed his door, threw himself down on the bed. A bubble stretched across the back of his throat and he pushed his head down into the crook of his arm, as if the suture between mouth and stomach would disappear if only he thrust his body into the bed further. Chris cried. Through his skull, the house was silent. He willed the tears down, until they too were completely inaudible, even if someone were to enter the room. Guilt: a silent song of stitches sung into himself. Three hours later, the front door opened. Dad sang “The Gambler” at the top of his lungs.

By fourteen, Chris knew all he could know. He did not know, for instance, whether his father owned any pornography. Certainly Chris had looked for it, in all of the usual places (sock drawer, underwear drawer, under mattress, in closet, in garage). A decrepit shed decked the backyard — “Dad’s space” — but was bolted padlock-stiff at all times. One afternoon, both parents at work, Chris had jimmied the lock with the help of Pinky Goodlowe. The red semi-rotten door yawned, boards scraping their teeth across the concrete floor as Pinky pushed inwards. Fingernails combing blackboard, the little hairs raised on the back of Chris’s neck as they broke the November-thin musk of the shed. Inside, they found an exercise bench and some free weights, a hundred odd pin-ups of men from the ’40s and even as early as the ’20s. In outdated gym clothes, they stretched from the darkness, bent in low leg lunges, squats, weight training. Abrupt veins erupted from their forearms and foreheads. Displaying double-pipe flexes, nineteen-year-old knuckleheads grinned Eddie-Haskell-ish. Charts of old wrestling techniques wallpapered the damp, knotty walls. Yellowed smiles stretched across faces that evoked another era so completely, it was as if their genetics had died out with them. Now they were locked up in the place Chris’s father came to be outside his life — to be with them, one of them.

“Can I have this?” Pinky asked. He held up what appeared to be one of several extra sets of handgrips. Chris tried, but couldn’t wrap his fingers around them. He shrugged. The grips disappeared into the back pocket beneath Pinky’s plaid shirttail.

Chris did not know if his father had other obsessions, did not know if his father might have been

his

age, for instance, the first time he consumed liquor, the first time he thought of girls. Chris did not know if Mr. Lane, in his youth, had been the sort of person who picked on others, or the sort who was picked on. In short, Chris could not imagine his dad being any different at any point in his life than he was now — at this very moment — stalking from the room, his ice cream spoon left in the bowl on the coffee table rather than taken to the kitchen, where a small blast of water would have saved the milk from hardening in thick muddy streaks.

Flicking through the stations, decisions were made: the best news, the best game show. But after nine, stillness stretched, reflected in the murky face of the unemployed TV (26 inches, wooden frame,

RCA, Made in U.S.A.

), the couch with its brown-and-orange afghan, the two armchairs, and one pair of his father’s shoes placed always to the left of the doorway. Chris did not know what bearing any of these items had on his father’s personality or the lives of his parents as a couple. Did not know if his mother was flirting with the jeweller when her voice rose at the end of a sentence like that. Did not know if Mrs. Lane enjoyed her job at the cannery, or if she wanted more out of life. If there was more, Chris hadn’t the slightest idea what it might be.

His parents were without history, without future. Chris imagined the farmhouse down the dirt road with the invisible old woman inside it, the past like a three-dimensional postcard. A snapshot of something still in existence but slightly out of reach. Like a picture on a faulty television, perpetually rolling, a zigzag of colour and a black line seemed to prevent Mr. and Mrs. Lane from interacting. Their conversations swept through the room, yet their faces were always bent out of shape, so that Chris could not see the expressions that went with the words.

Had it always been this way? It hadn’t. They had been exciting, funny, fusing arms around one anothers’ waists, making big productions of little things like Yahtzee shakes and throws.

His father’s shoulders tensed as he turned at the end of the hall with a backward glance.

By way of answer, Chris sniffed back. He didn’t bend to undo his laces as he toed off his shoes.

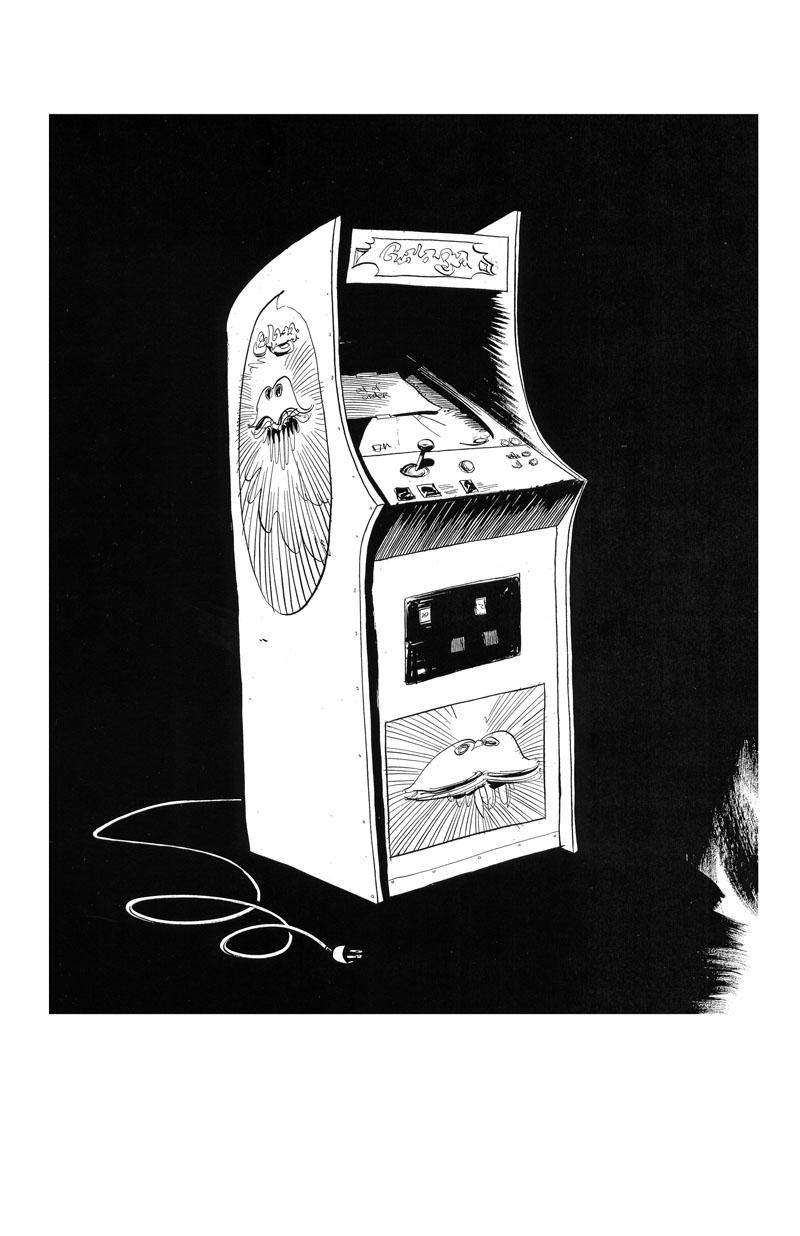

LEVEL 3:

GALAXIAN

PLAYER 1

“Get outside with your sister.” Mr. Lane poured milk over his Corn Flakes (Kellogg’s, packaged in London, Ontario) and left the carton on the table, lumbered into the living room. Mrs. Lane crossed the room and picked up the container of milk, flicked the triangular lip shut with her index finger.

Neilson

, the carton declared in red script.

44% Vitamin D. Pasteurized. Since 1893. Halton Hills, Ontario. Ottawa, Ontario. St. Laurent, Quebec. Meets and/or exceeds all Canadian Dairy Standards — guaranteed!

Its contents were boring, but its birthplace exotic. Halton Hills. Chris rolled the words around his mouth without opening it. His mother left the table with them.

Chris pushed the Sunday comics page aside. Beneath it, Minnesota’s Mondale was winning the battle of words against the Gipper. An arms race put on pause for a flag-waving race across America, while outside, down St. Lawrence Street, the high school band was beginning to assemble — among a series of half-decorated flatbed trucks and a tub of McDonald’s orange drink — to squawk out “O Canada!” on dinged French horns and barely sucked clarinet reeds. Born in Illinois, February 6, 1911 — the same month and same state as Chris’s grandfather — Ronald Wilson Reagan certainly wasn’t being billed as a Hollywood informer to the FBI during the Communist bedlam of the ’50s. Read here: champion of the Iran hostage crisis, Reaganomics, a system of strategic defense, “Peace Through Strength,” and on and on. But the American smudge of politics, thick as Charmin, went unread under Chris’s elbow. In a border-town rag, what was Mulroney but a big chin? The fourteen-year-old’s view of the world was in cartoon. Better yet, pixelation.

“Don’t you want to watch the parade?” Mrs. Lane asked, but she wasn’t looking at Chris. He shrugged, but her back was to him as she opened the refrigerator.

“I don’t understand how you could spend all that money there,” she said, but when she came over to the table again she lay a folded purple bill next to Chris’s elbow. The bulbous chemical tanks of Sarnia, Ontario stared up at him. He examined the industrial wasteland on the back of the ten-dollar bill.

Outside, kitty-corner to their house, came an onslaught of shattering glass. The VanDoorens were at it again. They scoured the town with a pickup truck, nimbly picked up broken glass, later transferred the toothy sea to a flatbed trailer, and — when they had accumulated a sufficient amount of it — sold it back to the factory to be melted down and reformed. Sometimes the crunch of it came as early as 5 a.m. By comparison, the Lanes were lucky today.

Chris’s mother cringed. “I don’t like this borrowing money from your friends. You pay John Paul back. But don’t ask for anything more for fireworks tonight.”

Chris folded the bill carefully in half lengthwise. He folded it in half the other way, then in half again.

“Thanks,” he mumbled, looking up for just a second before he bent beneath the table and shoved it into the top of one of his tube socks.

J.P. called less than a minute later. Mrs. Lane picked up, handed off the phone. She hovered, like she was waiting for something. Chris shuffled sideways, away from the china cabinet, but Mrs. Lane made no move toward its drawers, and instead stayed, suspended over him. He coiled the cord around his body and faced the wall so that the line wrapped all the way around him.