Kate Berridge (39 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Paradoxically, the more homogenised culture became, the more the cult of admiration for specific individuals grew, and there was also a more effective network through which to share the communal abhorrence of and fascination with murderers. Marie harnessed these currents of change to her own advantage and, pandering to an emerging mass market, rose in old age to the heights of her renown.

The cult of admiration was a by-product of an increasingly self-conscious society in which preoccupation with how one appeared in public was accompanied by a new interest in the status achieved by others. People held in high regard began to play a role in consumerism. To start with, aristocrats and clergy were the unlikely promoters of products in the pages of periodicals. The long list of named patrons recommending Mr Cockle's Antibilious Pills included ten dukes, five marquises and an archbishop; the âmany persons of rank and fortune' who corroborated the benefits of the British Antisyphilis treatment understandably preferred to remain anonymous. Gradually, from the nobility and gentry being the principal endorsers, other notable people became a source of personal recommendations.

In 1845 Marie herself featured in a celebrity endorsement of a health-giving tonic, promoted as curing an impressive list of ailments, including Indigestion, Flatulence, Head Ache produced by Indigestion, Sickness, Dropsy, Fits and Spasms (a sure cure in three minutes): âMadame Tussaud of Baker Street, Portman Square, has much pleasure in giving testimony to the great benefit she has received by taking the Elixir Sans Pareil during the last seven years.' Elsewhere she endorsed a firm of dyers.

The greater use of famous people to sell a vast range of consumer goods is reflected in Marie's own catalogue, which by 1844 had a circulation of 8,000 copies a quarter, rising to 10,000 three years later.

Her âbiographical sketches' are flanked by advertisements. Amid the endless ads for Ventilating Hats and Invisible Hair are notices for Nelson's Gelatine, Royal Victoria Carpet Felting, Albert Cravats and the Wellington Surtout, a ânew, light, repellent overcoat for all seasons'. Elsewhere, Napoleon was being used to promote various products including shoe blacking and ink, and the showmanâstrongmanâexplorer Belzoni, endorsed hair dye (perhaps exploiting the link between Samson and hair). Less flattering product association was that posthumously foisted on William Cobbett: âIn his

Register

for June 1832 the late William Cobbett MP described the suffering he had endured for 22 years from the use of imperfect trusses.' Relief could have been supplied by Mr Cole's patented improved product. Technological advances in printing meant that for the first time celebrity likenesses were used on pre-packaged foods for the mass market, on pot lids for such products as relish, meat paste and sauces. The Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel were all used in this way, and even Prince Albert's face appeared on tubs of shaving cream.

One can see very clearly the scaffolding of celebrity culture in the midst of which Marie was proving herself a talented architect. The dissemination of information about public figures in print was the first step, followed by dissemination of their pictorial likenesses.

Carte de visite

mania, the craze for collecting small photographic portraits of the famous, happened after Marie's death, but in her lifetime photographyâor âdrawing by light'âwas in fits and starts attempting to close the gap between original and copy. In an 1842 trade magazine an advertisement for Madame Tussaud's exhibition appears beside one promoting photographyâat this time still being marketed as an aid for artists: âBy this process the artist will derive great advantage in having a perfectly accurate likeness, from which he can paint a portrait, saving much of his own time and trouble as well as the time of his sitter.' While the photographic process was much improved during her lifetime, it was not until the decade immediately after her death that the commercial scope of the genre was realized.

Last but not least in the nascent cult of celebrity was the impact of mass-produced figurines. From 1843 to 1850 the growing popularity of non-royal civilian likenesses at the waxworks was mirrored by figurines of people from all walks of lifeâentertainers, certain popular

clergymen, and statesmen such as Wellington and Peelâbecoming the must-have home accessory to place on the pianoforte, somewhere near the aspidistra. The Staffordshire potteries were but one producer which profited from this boom, and one of their best-sellers was Jenny Lind. Known as the âSwedish Nightingale', she was one of the first entertainers to experience a mob of fans. She made her London debut in 1847, and became a favourite with the Queen. She exemplifies the advent of the celebrity as a mass-market phenomenon crossing the class divide, and naturally her likeness was installed at Baker Street. As a magazine called

The Era

put it, âThe queen in her palace, the lady in her boudoir, the men at their clubs, the merchant on the change, the clerk in his office, and indeed all sorts of people from the most exalted to the lowest members of society spoke of Jenny Lind.' Naturally her name was used by opportunist advertisers to promote goodsâplausibly in the case of street ballads, but less so when it came to men's clothes. Lind hinted at a new star power that would eventually drive the aristocrats out of the ads.

One of many lessons learned at Curtius's knee was that crime paid, and the dividends for Marie and her family were particularly good in 1849 when two murder stories were national sensations. On 21 April James Blomfield Rush was executed at Norwich for the triple murder of his landlord and two members of his landlord's family. Public interest was so intense that special trains were laid on for visitors to the crime scene. Later that year, on 13 November, an estimated 50,000 people attended the public execution in London of Maria Manning and her husband, George, for the murder of her lover, Patrick O'Connor, a retired customs officer. The sexual frisson of a

ménage à trois

was enhanced by titillating reports of Maria Manning's tight-fitting black-satin dressâone paper said that the attention given to this ruined the satin industry for the next twenty years. But for Marie, watching from the wings, this was a boon. The wax figures took up their place in the Chamber of Horrors, which was permanently packed as a result of the voyeuristic interest.

Punch

once again launched a hostile attack on Madame Tussaud, who âdisplays the names of the Mannings and Rush as the manager of a theatre would parade the combination of two or three stars on the same evening'. The

Art Journal

also inveighed against the glamorization of crime: âShould such indecent additions continue

to be made to this exhibition, the horrors of the collection will assuredly preponderate. It is painful to reflect that although there are noble and worthy characters really deserving of being immortalised in wax, these would have no chance in the scale of attention with a thrice-dyed miscreant.' By way of defence, the Tussauds took to publishing the following apologia: âThey assure the public that so far from the exhibition of the likenesses of criminals creating a desire to imitate them, Experience teaches them that it has a direct tendency to the contrary.' They also decided on the back of the Mannings to expand their aversion therapy: âThe sensation created by the crimes of Rush and the Mannings was so great that thousands were unable to satisfy their curiosity.' The most telling aspect of the Victorian fascination with murder was the popularity of figurines of murderers and ceramic models of the crime scenes, at a time when Victoria's brood of rosy-cheeked princes and princesses inspired no Staffordshire portraits and comparatively few prints. Cheap accounts of murders also enjoyed a circulation of millions when national newspaper circulation was still hovering around a hundred thousand.

By questioning the status of kings as divine rulers, in the Paris of her early life the philosophers whom Marie described as family friends had set in train a process that would see the world transformed before she died. As kings and queens were demystified, they became more like the servants, not the rulers, of their subjects. Marie's wax exhibition documents a power shift from the subservience of the subject to the dominance of the fan. The last major tableau of the royal family that Marie herself lived to see installed was entitled âSweet Home', after âHome, Sweet Home', a song that had greatest-hit status in the nineteenth century, selling over 100,000 copies in sheet-music form in its first year alone. It was like a theme song for an era that celebrated domesticity. It was also a suitable caption for the wax group that represented Prince Albert and Victoria at home, âsitting on a magnificent sofa' and âcaressing their lovely children'. This image of family harmony was striking for its simple depiction of the royals as ordinary peopleââthe whole intended to convey an idea of that sweet home for which every Englishman feels that love and respect which can but end with their lives'. For visitors, it was as if they had just been announced and entered the royal drawing room.

This family group was a radical view of monarchy, for it played on ideas of the royals' similarity to those viewing them, not the distance which had been so forceful in, for example, that first crowd-pleasing wax tableau of the Grand Couvert of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. The ceremonial at Versailles had been intended to emphasize the distance between monarch and subjectâas Sénac de Meilhan had said in

Ancien Régime

France, âIt is good for the monarch to come close to his subject, but this needs to be through the exercise of sovereignty and not by the familiarity of social life. This familiarity allows too much to be seen of the man, and reduces respect for the monarch.'

It was as if very gradually the royal family were becoming an entertainment, like a family saga in one of the new mass-market inexpensive novels, of interest for their private life and personalities, and access to them in the private realm was increasingly regarded as a right. There was also a sense in which, as the royals became less regal, the middle classes subscribed with gusto to delusions of grandeur. While Victoria displayed her bourgeois taste in the style of her royal residences and convinced the public that her castles and palaces were primarily homes, the newly affluent sector of her subjects went on a frenzied buying spree to assert that the Englishman's home was his castle.

The âSweet Home' tableau of the Royal Family was in sharp contrast to the other major installation that people continued to flock to see, which was the shrine of Napoleon. This juxtaposition highlights the forces of change that had coursed through Marie's long life. For as the royal family seemed to become more ordinary, and were seen as similar to the public who were their subjects, individual achievers were increasingly seen as superior and different from the public who were their fans. This elevation of ordinary men into almost superhuman beings was exemplified by the cult of Napoleon. If deference for the royals was diminished, then there were quasi-religious connotations to the reverence with which the public filed past Napoleon's toothbrush and blood-stained counterpane, and stood before one of his teeth (the catalogue said that during the extraction âthe Emperor suffered much'). For Marie, Napoleon was one man who never let her down, and with whom she had a blissfully happy partnership that saw her through good times and bad, for richer and richer and richer until death did them part.

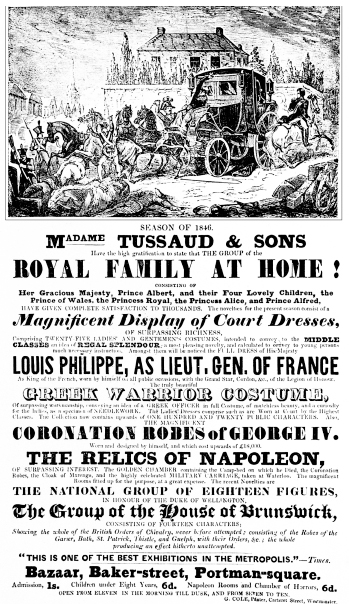

Napoleon's carriage illustrates poster describing the collection in its prime, 1846

Napoleon was resurrected from death by the sheer volume of commercial entertainments that he featured in. Even his cancerous stomach, preserved like a saint's relic and labelled as historical evidence of the cause of the great man's death, could be seen at the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, until a French visitor's protest restored it to anonymity when the card identifying the controversial specimen was removed. Dickens reported the fracas when the imperial relic was spotted: â“Perfide Albion!” shrieked a wild Gaul whose enthusiasm seemed as though it had been fed on Cognac. “Perfide Albion!” again and more loudly rang through the usually quiet hall. “Not sufficient to have your Vaterloo Bridge, your Vaterloo Place, your Vaterloo boots, but you put violent hands on the grand Emperor himself.”â¦From that time the pathological record of Napoleon's fatal malady has been unnumbered andâto the millionsâunrecognisable.' Doing the rounds elsewhere was a wax likeness of the emperor with mechanical lungs. The publicity posters

screamed, âNapoleon is not Dead! You may see and hear the phenomenon of respiration, feel the softness of the skin and the elasticity of the flesh, the existence of the bones, and the entire structure of the body.'