Killing Patton The Strange Death of World War II's Most Audacious General (26 page)

Read Killing Patton The Strange Death of World War II's Most Audacious General Online

Authors: Bill O'Reilly

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Military, #World War II, #History, #Americas, #Professionals & Academics, #Military & Spies, #20th Century

So Helena had good reason to be scared that some sort of severe punishment awaited her.

Then, before the kapo could betray her, fate intervened. The date was March 21, 1944. Helena had been a prisoner in Auschwitz for two years. That day was also, coincidentally, the birthday of an SS guard named Franz Wunsch. Known to be an avowed “Jew hater,” the twenty-two-year-old Wunsch was in charge of the Canada work detail. That day, he took the liberty of stopping the sorting process for a short time, and asked if anyone would sing for him. Recognizing the opportunity for what it was, Helena volunteered. Her voice soon wafted through the detritus of the sorting house, a stunning contrast to the sadness of ransacking dead people’s clothing.

Wunsch was transfixed.

He immediately fell for the raven-haired Helena. Not long after, he took the bold risk of handing her a love note. Relations between guards and Jews were strictly forbidden, although they were a common occurrence. The guards took the risk for the sex. The prisoners took the gamble to save their lives.

But Helena was not interested—not at first. “He threw me a note,” she will later remember. “I destroyed it right there and then. But I could see the word ‘love’—‘I fell in love with you.’”

Helena was appalled. “I thought I’d rather be dead than be involved with an SS man. For a long time afterward, there was just hatred. I couldn’t even look at him.”

But the smitten Wunsch was persistent. Every day, he would seek her out among the women at work in Canada. He would sneak her cookies, and took special interest in her welfare: the SS guard was trying to buy his way into her heart.

Then an incredible thing happened. Helena’s sister, Rozinka, along with her two children, arrived at Auschwitz via a train from Slovakia. Wunsch noticed them.

“Tell me quickly what your sister’s name is before I’m too late,” he demanded of Helena.

“You won’t be able to,” she replied coolly. “She has two young children.”

Wunsch was taken aback. “Children can’t live here.”

Finally, Helena gave him her sister’s name. Wunsch then raced to the crematorium and, for show, beat Rozinka in front of her children, explaining to his fellow SS guards that she had disobeyed an order to work in Canada. The guards looked the other way as Wunsch dragged her off, leaving Rozinka’s young daughter and infant son to die. Harsh as it was, Wunsch saved the woman’s life.

Helena, however, now owed a debt to the SS guard.

“In the end, I loved him,” Helena will recall of the affair that began that day. “But it could not be.”

Franz Wunsch was sent to the Russian front as the war came to an end, along with many of his fellow guards. His last act of kindness was making sure that Helena and Rozinka each had a pair of warm fur-lined boots to help them survive the winter.

When the soldiers of the Soviet Sixtieth Army entered the camp on January 27, they were particularly taken with the plunder inside the building known as Canada. Almost a million articles of women’s clothing and half as many men’s garments still waited to be sorted.

But that job no longer fell to Helena and Rozinka. Their nightmare was over—at least for the moment. Working in Canada meant they had enjoyed better rations and regular access to water. They had not been beaten, and were extremely healthy compared to so many others in the camp. So they began walking home to Slovakia, eager to put as much distance between themselves and Auschwitz as possible.

But isolated country roads are never completely safe, even in peacetime. Now, as Helena and Rozinka sleep in the barn, their nightmares begin again. Soviet soldiers reeking of alcohol suddenly invade their small sanctuary. It is not one Red Army soldier, or even two, but an entire gang. They are thin from their long days of marching. Their clothes are threadbare. One by one, the women sleeping in the barn are wrestled to the ground if they try to run and then brutally raped, sometimes twice. “They were drunk—totally drunk,” Helena later remembers. “They were wild animals.”

As this goes on, Helena disguises her looks, messing her hair and covering her face in grime to make herself appear unattractive. The plain and matronly Rozinka helps shield her sister from the soldiers by pretending to be her mother. Some of those attacked show the Russian shoulders their camp tattoos, and cry out that they are Jewish, hoping it will make the Russians see them as undesirable. The soldiers’ reply, delivered in terse German from those who have picked up a smattering of the language, is coarse: “Frau ist Frau”—“A woman is a woman.”

Somehow Helena and Rozinka escape being raped. However, they must silently listen to the screams of those women being violated, and then the heart-wrenching silence when the act is completed.

The Russian soldiers are not satisfied with mere sexual conquest. They are animals, biting away chunks of women’s breasts and cheeks and savagely mauling their genitals. Many strangle their victims after the act, silencing them forever. Perhaps they prefer murder to the personal shame of their victims glaring at them in hatred.

“I didn’t want to see because I couldn’t help them,” Helena remembers. “I was afraid they would rape my sister and me. No matter where we hid, they found our hiding places and raped some of my girlfriends.”

Russian soldiers raped millions of women during the course of the war.

1

A large proportion of these women will contract venereal disease from their attackers. Some of them will commit suicide afterward. Others will become pregnant but refuse to carry a rapist’s baby to term and will find a way to abort the fetus. Many of those who give birth to these children of rape—

Russenbabies

, as they will be known—will abandon them. For some women, such as those in the barn, the liberation of Auschwitz was not the end of their suffering, but the beginning of a new kind of suffering.

“They did horrible things to them,” Helena will recount decades later, from her new home in the Jewish nation of Israel, the image of kicking, biting, and clawing at a young Soviet officer to prevent herself from becoming a victim of rape still clear in her head.

“Right up to the last minute we couldn’t believe that we were still meant to survive.”

* * *

Many Auschwitz survivors find there is no shelter, even when they make it back to their hometowns. All throughout Eastern Europe, Joseph Stalin and the Russian military machine have taken advantage of the mass Nazi deportations of Jews to steal homes and farms and give them to the Russian people. This is just the start of a massive forced migration that will see millions of non-Soviets in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Poland forced out of their homes. They will be left to resettle in the ruins of the Nazi occupation, in lands that will be without industry, farming, or infrastructure.

Like Helena and Rozinka Citrónóva, Linda Libusha is a Slovak who has survived Auschwitz. As she walks the streets of her beloved hometown of Stropkov, from where she was arrested and led away in March 1942, she believes the nightmare of the camps may be finally behind her.

But Linda doesn’t recognize anyone during her stroll down the main street. It’s as if everyone she ever knew has vanished. When she knocks at the door of the house in which she grew up, it is answered by someone she has never seen before, a heavyset man with a red Russian face. Over his shoulder she can see the same familiar rooms and hallways where she once played as a child—and where this foreigner now makes his home.

The Russian takes no pity on the death camp survivor.

“Go back where you came from,” he says, slamming the door in her face.

16

T

RIER,

G

ERMANY

M

ARCH

13, 1945

M

ORNING

George S. Patton is on the move.

Finally.

Sgt. John Mims drives Patton in his signature open-air jeep with its three-star flags over the wheel wells. The snows of the cruel subzero winter are melting at last. Patton and Mims pass the carcasses of cattle frozen legs-up as the road winds through Luxembourg and into Germany. Hulks of destroyed Sherman M-4s litter the countryside—so many tanks, in fact, that Patton makes a mental note to investigate which type of enemy round defeated each of them. This is Patton’s way of helping the U.S. Army build better armor for fighting the next inevitable war.

It is a conflict that Patton believes will be fought soon. The Russians are moving to forcibly spread communism throughout the world, and Patton knows it. “They are a scurvy race and simply savages,” he writes of the Russians in his journal. “We could beat the hell out of them.”

But that’s in the future, after Germany is defeated and the cruel task of dividing Europe among the victors takes center stage. For now, it is enough that the Third Army is advancing into Germany. Patton has sensed a weakness in the Wehrmacht lines and is eager to press his advantage.

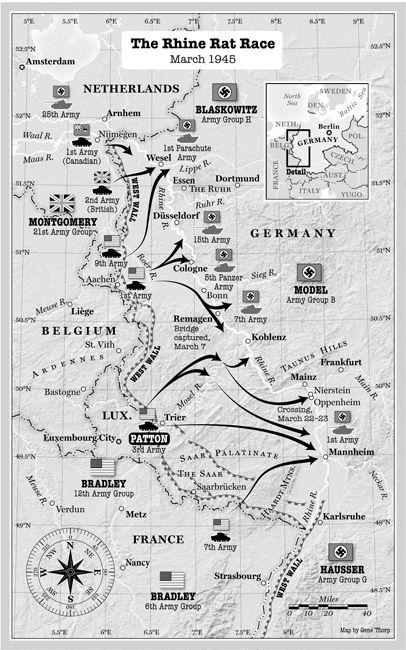

It was four weeks ago, on February 10, when Dwight Eisenhower once again ordered Patton and his Third Army to stop their drive east and go on the defensive and selected British field marshal Bernard Law Montgomery to lead the massive Allied invasion force that will cross the strategically vital Rhine River. It is a politically astute maneuver, because while Montgomery officially reports to Eisenhower, the British field marshal believes himself to be—and is often portrayed in the British press as—Eisenhower’s equal. Winston Churchill publicly fueled this portrayal by promoting Montgomery to field marshal months before Eisenhower received his fifth star, meaning that for a time Montgomery outranked the supreme commander of the Allied forces in Europe. Now Eisenhower’s decision to throw his support to Montgomery’s offensive neatly defuses any controversy that might have arisen over Eisenhower giving Patton the main thrust.

Stretching eight hundred miles down the length of Germany from the North Sea to Switzerland, the Rhine is the last great obstacle between the Allies and the German heartland. Whoever crosses it first might also soon know the glory of being the first Allied general to reach Berlin.

It is as if Patton’s monumental achievement at Bastogne never happened.

“It was rather amusing, though perhaps not flattering, to note that General Eisenhower never mentioned the Bastogne offensive,” he writes of his most recent discussions with Eisenhower. Then, referring to the emergency meeting in Verdun that turned the tide of the Battle of the Bulge, he adds, “Although this was the first time I had seen him since the nineteenth of December—when he seemed much pleased to have me at the critical point.”

Even more galling, not just to Patton but also to American soldiers, is that Montgomery has publicly taken credit for the Allied victory at the Battle of the Bulge. Monty insists that it is his British forces of the Twenty-First Army Group, not American GIs, who stopped the German advance.

“As soon as I saw what was happening,” Montgomery stated at a press conference, at which he wore an outlandish purple beret, “I took steps to ensure that the Germans would never get over the Meuse. I carried out certain movements to meet the threatened danger. I employed the whole power of the British group of armies.”

What Montgomery neglected to mention was that just three British divisions were made available for the battle. Of the 650,000 Allied soldiers who fought in the Battle of the Bulge, more than 600,000 were American. Once again, Bernard Law Montgomery used dishonest spin in an attempt to ensure his place in history.

Montgomery’s stunning January 7 press conference did considerable damage to Anglo-American relations.

1

To Patton, it seems outrageous that Montgomery should be rewarded for such deceptive behavior.

Yet despite the fact that four American soldiers now serve along the German border for every British Tommy, Eisenhower has caved in to pressure from Churchill and selected Monty to lead the charge across the Rhine. Still, the reasons for this decision are practical as well as political: the crucial Ruhr industrial region is in northern Germany, as are Montgomery’s troops. Theoretically, Monty is capable of quickly laying waste to the lifeblood of Germany’s war machine.

Nevertheless, the decision makes George S. Patton furious.

On this chilly Tuesday morning, the cautious and finicky Montgomery is still ten days away from launching Operation Plunder, as the Rhine offensive is known. So Patton, sensing an immediate weakness in the German lines, has convinced Eisenhower to let him attack, two hundred miles to the south. The plan to invade southern Germany’s Palatinate region came to Patton in a dream. It was fully formed, right down to the last logistical detail. “Whether ideas like this are inspiration or insomnia, I don’t know,” he writes in his journal. “I do things by sixth sense.”

Patton’s military ambitions for the assault are many, among them the devastation of all Wehrmacht forces guarding the heavily fortified Siegfried Line.

2

Privately, however, he admits that not all his goals are tactical. The war is now personal. Patton has endured countless slights and setbacks. Many are of his own doing, but just as many are clearly not. Patton, at heart, is a simple man who wears his emotions on his sleeve. This makes him extremely poor at the sort of political posturing at which rivals such as Montgomery excel.