Kiss and Make-Up (11 page)

Authors: Gene Simmons

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #Musicians, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Rock Stars

As the months dragged on, Paul and I realized that Wicked Lester was unraveling. At one point we looked at each other and said, “You know what? This is not it. Whether we get a contract or not, this isn’t what we want.” In Wicked Lester there were all these three-part harmonies that sounded like the Doobie Brothers, and there wasn’t nearly enough guitar. Paul and I had started writing other material, songs like “Deuce” and “Strutter,” and we decided to put together the band we had always dreamed about. It’s not that our tastes had changed, really; rather, we became braver about making the band reflect our tastes. I remember going to see the New York Dolls early on. We knew that they looked like stars, and that’s what we wanted to be: stars. We were in awe of them. But when they started playing, we looked at each other and said, “We’ll kill them.”

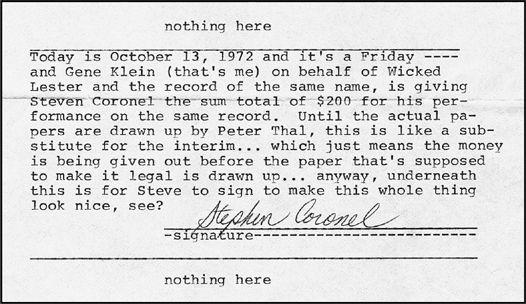

This is a letter to my best friend, Stephen Coronel, asking him to leave Wicked Lester. In the early days I negotiated, wrote, and typed all our documents.

Initially, our idea was to fire Tony and Brooke and remake Wicked Lester in our image. But when we announced this to the other guys, they weren’t happy about it. Our drummer, in particular, said that he was not leaving the band and would honor the contract. So we had no choice but to quit ourselves. We had a contract with Wicked Lester, but we didn’t have a contract with each other, so Paul and I just left.

At just around the same time, we suffered another major blow to our fledgling recording career. We had a loft on Canal and Mott Streets that we used as a practice space and a crash pad. One day we came in to practice, and it was like we had stumbled into the wrong room. The place was empty. Picked clean to the bone. We couldn’t believe it—our equipment had been stolen, down to the last little piece. We had only the guitars we were carrying, so Paul and I went down to the sidewalk and played like street performers.

I wasn’t optimistic about the band that might or might not rise from the ashes of Wicked Lester. Paul wanted to start another band with me, but I told him that I was going to go upstate, back to Sullivan County. I planned to look for a guitar player and start another band, and I promised to call Paul when I got back. He said, “No, no. I’ll come along.” So we went hitchhiking up there. We had a mission, as I remember: we were looking for this hot guitarist who was the big guy on the local Sullivan County scene. Right at the beginning of the trip, we got picked up by these two black guys. We were dressed in fur and leather, the whole aspiring-rock-star deal. We thought they would kill us. But they were nice guys, as it turned out. We started talking, and they weren’t going as far as we were. So we got out and flagged down the next car we saw, and it happened to be a VW bus with these two girls in it. They weren’t attractive. They were unattractive. But they were nice, and they invited us back to their place. It was a farmhouse, and it was filthy, one of those hippie crash pads. Not only was it filthy, with dogs everywhere,

but it was stifling hot. It was like a furnace in there, because the heat wasn’t regulated, and it was the middle of winter.

Paul and I went to sleep in one room, and the two girls were in the other room. In the middle of the night one of the girls got up and went to feed the dogs, and I woke up and saw her naked silhouette. I was going to go up to her and see if I could transact a little business, and Paul elbowed me. He was always more cautious in these situations than I was. “Cut it out,” he said. “You’re going to get us kicked out into the cold.” So I went back to sleep. But then in the morning she came into the room and opened the front door. The blast of cold air was so invigorating. I went to stand by the door, and I took the occasion to tell her about what had happened the night before. I said, “You know, last night there was a moment when I woke up and saw you, and I was aroused, and I thought about making an advance, because you were quite beautiful.” I made a long speech, and at the end of the speech, she said, “I’m sorry. Hold on a second.” She reached into her bag and pulled out a hearing aid and put it in her ear. I had to repeat this whole long speech a second time, just as flowery as the first one. At the end of it she looked at me, and I was afraid that she was going to tell me that she hadn’t turned the hearing aid on. But instead she said, “Oh, you wanna fuck?” I did, so we went out to the barn, and we lay down on some blankets, and we began to get acquainted. But her hearing aid was on, and every time my head came near hers, I heard feedback noise from the hearing aid. It scared the pants off me at first—actually, they were already off, but it was incredibly disconcerting. Eventually I got used to it.

We never found the hot guitarist in Sullivan County. It didn’t really matter. The trip was like a rite of passage, a way for Paul and me to bond and to reassert our devotion to creating the best band imaginable. What began to rise to the top, ironically, wasn’t the musical aspect of the band but the entire package: the showmanship, the costumes, the hair, and so on. We weren’t wearing makeup yet, but we were heading in that direction, thanks in part to this unshakable faith, on both our parts, that this was the right way to get noticed in the rock world. Glam rock hadn’t hit yet and rock

music was still mostly the province of hippies, guys in jeans and girls with long hair. How you looked wasn’t as important as the music you made and the way you felt about each other. We didn’t buy into that. I still remembered the first thing that struck me about the Beatles when I saw them on

Ed Sullivan

, and it wasn’t their music. It was the way they looked: perfectly coordinated, cooler than cool. They looked like a band.

Even in Wicked Lester, the entire band toyed around with more theatrical models of rock and roll. Steven drew some sketches of the different personalities that we imagined for ourselves. Brooke was going to wear an undertaker’s hat. Paul was going to dress up as a gambler, with a cowboy hat and twin guns and so on. I was going to dress up like a caveman and drag my bass behind me. Steven was going to be an angel with wings. After he sketched out the plan, he actually went ahead and built his costume; he made an angel rig with movable wings in back. Clearly the plan needed to have some of the wrinkles ironed out. But we were on the same wavelength, which was that we needed to keep pushing the visual appeal of the band. We weren’t content to just stand there and strum our guitars. That wasn’t enough. We wanted to make a big splash.

A band is

like a puzzle. Some of the pieces get filled in right away, and some of them take a little longer. At first Paul and I had a vague idea of what we wanted our band to be like, but as time went on we began to home in on what we were trying to achieve. We saw plenty of bands doing things we didn’t like, and every time we saw them, we were able to refine our vision. Paul and I were primarily songwriters and singers. We could play instruments, but at demo level. We needed the rest of the band to fully realize our vision.

After the Mott Street disaster, we got ourselves a loft at 10 East Twenty-third Street. It was the same kind of thing, half practice space, half crash pad. What we mainly did, when we weren’t sneaking girls up there, was sit around and brainstorm about the kind of musicians we needed. First on the list was a drummer. One afternoon I ran across an ad in

Rolling Stone

that said, “Drummer available—will do anything.” I called the guy on the telephone, and even though he was in the middle of a party, he took my call. I introduced myself and said we were starting a band and that the band was looking for a drummer, and was he willing to do anything to make it? He said that he was, right away.

He answered almost too quickly. So I slowed him down. “Look,” I said. “This is a specific kind of band. We have very particular ideas about how we’re going to make it. What happens if I ask you to wear a woman’s dress while you play?” He covered up the phone and repeated my question to a guy in the background, who laughed. I went on: “What happens if I ask you to wear red lipstick or women’s makeup?” By now, the people in the background were beside themselves. But the drummer answered my question. “No problem,” he said. “Are you fat?” I said. “Do you have facial hair?” Because if he did, I explained, he would have to shave it. We didn’t want to be like a San Francisco hippie band. We wanted to be big stars, not medium stars who looked like hippies. We were going to put together a band that the world had never seen before. We were going to grab the world by the scruff of its neck and …

One of our first shows—in the early days we would play eight shows a week. This was the original leather outfit I wore with a skull and crossbones on the chest. My sweat would eat through the leather, so I cut out a hole in the chest to get some air.

I guess I went on too long, because at some point the drummer stopped me. “Why don’t you just come and see me?” he said. “I’m playing at a club in Brooklyn Saturday.”

Saturday came, and Paul and I took the subway all the way down to the end of Brooklyn, to this small Italian club—whose clientele could easily have been actors on

The Sopranos.

There were maybe twenty people there, all of them milling around, drinking beer, and watching this trio on stage. The bass player and guitar player looked like soldiers in the Genovese family. The drummer was

something else entirely. He had a shag haircut that looked like Rod Stewart’s on a good day, and he had a big gray scarf. He outdressed everybody in that club, and he looked like a star.

They were playing mostly soul covers, and when they did “In the Midnight Hour,” the drummer started to sing, and this Wilson Pickett—style voice came out of him. Paul and I said, “That’s it, that’s our drummer.” His name was Peter Criscuola, and we shortened it to Peter Criss. We brought Peter into our loft on Twenty-third Street, and we began to play as a trio. It was 1972 and things were moving more quickly now: we had songs we were happy with, and our look was starting to crystallize—we were even starting to wear makeup, although it was far cruder than it eventually became.

This new version of the band still needed to go before Epic to see if they were interested. The record label sent down the vice president of A&R. He came to the loft, where we had set up a little theater—ten rows of four seats—to simulate the feeling of playing in front of a live audience. He sat down, and we played the three songs that we were most confident about: “Deuce,” written by me, “Strutter,” written by Paul and me, and “Firehouse,” written by Paul. The set went well, although we weren’t sure that the A&R guy exactly understood what we were about. I was wearing a sailor’s uniform, and I had my hair puffed out and painted silver. At the end of “Firehouse,” there’s a stage move we had worked out where Paul grabbed a fire pail filled with confetti and tossed the contents over the audience. He went for the pail, and as he flung it toward the seats, I saw a look of terror on the A&R guy’s face. Clearly, he thought the pail was filled with water. He leaped to his feet and headed for the door. To get there, he had to get past Peter Criss’s brother, who was hanging out at the loft. He was a navy guy who was spending the afternoon with us, and he had been drinking hard. As the A&R guy went past him, the brother made a kind of gurgling noise, then threw up on the A&R guy’s shoes. “Okay,” the A&R guy said on his way out, “I’ll call you.”