Kiss and Make-Up (39 page)

Authors: Gene Simmons

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #Musicians, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Rock Stars

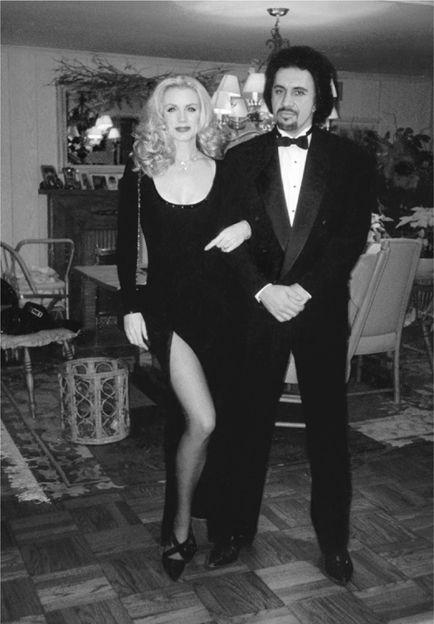

Shannon and me on New Year’s Eve in the mid-1990s.

Tupac announced to the audience that he had a surprise, and we walked out onto the stage. The first guy who jumped up was Eddie Vedder. Then the whole crowd jumped to its feet. We were back.

The Grammy Awards

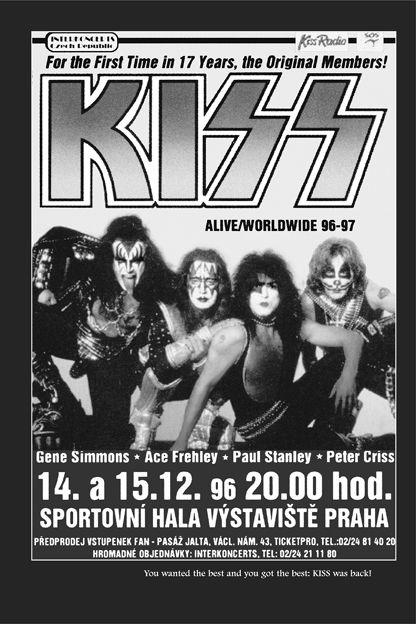

ceremony was the beginning of our comeback trail. Within about a month Doc decided to book Detroit’s Tiger Stadium as the first show. It sounded like the height of lunacy to us. The safe way would have been to test our act in a smaller market, someplace like Dothan, Alabama, where we could sharpen our act and the problems in the show wouldn’t be scrutinized quite so intensely. But Doc booked a baseball stadium in Detroit. To be honest, we weren’t even sure we would sell out the show. Tickets went on sale one Friday night. At six in the morning on Saturday, Doc called me at home to tell me that he had some good news and some bad news. I asked for the bad news first. “Well,” he said, “we don’t have any more tickets to sell.” We had sold out the whole stadium—about fifty thousand seats—out in under an hour.

I immediately called Peter and told him. He said, “Yeah, yeah,” in a voice that made me believe he was still half-asleep or didn’t understand what I was telling him. But by the end of the conversation, he was hooting and hollering.

Peter was so jubilant that for a minute I thought this tour might go smoothly. But it wasn’t to be. We had a photo session with Barry Levine, who had worked with us back in 1976, and Ace complained that it was taking too long. Though we had intense personal training sessions with weights and aerobics to prepare us for the concerts, halfway through his sessions Ace would stop. Peter didn’t stop, but every step of the way he complained that the guy who was working him out was too demanding. Once Ace walked up to me in the parking lot of the rehearsal hall and said, “I still don’t have my weekly check, and if I don’t get it by five o’clock today, I’m quitting the band.” He always thought, and still does, that people are trying to cheat him. To Ace it was always a conspiracy to do him in.

Ace Frehley, more than anyone else in the band, seems to have a dark cloud over his head. He was and continues to be fearless in almost everything he does. In some ways, it is a quality I have always found fascinating, because I don’t have it myself. Where I am overly cautious about my health, Ace is the extreme opposite. He would drink until he passed out. He has used enough drugs to kill a lesser man. He has always been and continues to be unrepentant about all of that. He never cared about the effect his behavior had on anything or anyone: on the band, his personal relationships, or his health.

I have to admit to being completely stumped. If someone were to jump off a building to commit suicide, at least he or she would have an audience. Ace prefers privacy, though—he never minded numbing himself alone. In fact, he seemed to relish the idea of going back to his room and knocking himself out. He would spend off days in his room and never come up for air. But despite all the self-destructive behavior, Ace is bright. He would tinker with little gadgets; he actually designed and built his own rocket shooting device for his guitar in the early days when the band was first touring. I was in the dressing room watching Ace solder wiring on his guitar for this effect, and as he turned to face me I saw him solder his thumb to the guitar. When he felt the pain, he screamed and yanked his hand away, but part of the skin of his thumb remained soldered to his guitar.

Ace and Peter both have managed to cheat death more times than I can count. When KISS opened up one of our early tours in Florida in the days when guitars were still connected to amplifiers by jacks (electric wire connectors), Ace was electrocuted onstage in front of the audience but rejoined us within a few minutes to finish the show. Peter was once hit with an M-80 firework that was thrown onstage and was knocked off his drum riser. He had to be taken to

the hospital. After he returned, the show went on. Ace has been chased by the police at speeds of 100 mph and has walked away from crashes reasonably intact. He and Peter have both been in a number of terrible accidents and should have been killed. But Paul and I had put up with much of that throughout the years, and we were prepared to deal with it again.

Before the Tiger Stadium tickets went up on sale in 1996, Doc McGee wanted to do a press conference in New York. And he had this idea doing it at the New York Public Library, on Forty-second Street and Fifth Avenue. I understood his rationale—he wanted a place that was easily accessible to all the national press—but I didn’t want that locale. Libraries had nothing to do with KISS. Instead I suggested that we go to the United Nations, which could represent KISS’s global reach. Doc liked that, but he couldn’t get the right permits. Then I remembered that in 1981 Diana Ross had gone onto the USS

Intrepid

aircraft carrier for a small press conference. I suggested to Doc that we do a KISS press conference on the

Intrepid

, which is permanently moored in the Hudson River, on Manhattan’s West Side. Even though it was raining, the event was a huge success—Conan O’Brien introduced us, and we managed to attract television and press from fifty-two countries. When we took questions, I made sure that we had big signs in front of us with our names. Ace thought I was crazy. He thought everyone knew who he was. I had to explain to him that some countries didn’t have any idea who KISS was anymore. Amazingly, at the press conference itself, Ace came off fine. Better than fine, in fact—he was very charming, very self-effacing.

Those moments of good behavior were rare, though. We took over Cobo Hall in Detroit, where we had recorded

Alive!

, to rehearse for the Tiger Stadium show. Peter, Paul, and I, plus the road crew and everybody else, got there and got settled. While we were unpacking, someone came up and told me that Ace had not yet made it to Detroit. This was to be the first day of rehearsal for our biggest tour in almost two decades, and he couldn’t get there on time. We booked him another flight, and he missed that one too. Then we booked a third one, which he also missed. When Ace finally walked

into rehearsal and said something about how hard it was to pack, I basically tore him a new asshole. I told him he was a loser, that this was his last chance to get on his feet. I told him that he should be ashamed of himself, keeping the entire band and crew waiting. “If you can’t do the job,” I said, “get the fuck out.”

Ace exploded right back at me and told me to go fuck myself. Then he left. When he was gone, Paul turned to me and asked me to smooth things over. “He’ll listen to you,” he said. So I had to swallow my pride and go out there and say in a gentle tone, “Look, Ace, whatever else is going on in your life, you owe it to your fans to show them that you can still be a great guitar god.” This appealed to him, and he came back and started rehearsing. It didn’t stop him from showing up late at other times, though.

At around this same time, I wanted a band biography to be written for the reunion tour, and I wanted someone famous to do it. I tried to get Stephen King, but he was unavailable. Then I tried Steven Spielberg, but he was also unavailable. Then I thought about Bob Guccione, the editor of

Spin.

At that point,

Spin

was every bit as big as

Rolling Stone.

So even though we had once sued Guccione for printing and distributing an illegal and unauthorized KISS magazine in the 1970s, he took my call and we chatted. He agreed to write the bio, which would be a short thing, like a press release. Along the way I told Guccione about our reunion tour and the fact that we were getting back together. I wanted him to put us on the cover of

Spin.

He thought it was a good idea, although he wasn’t sure it should be the whole band. He wanted a cover picture of me alone. While talking to him, I saw a larger opportunity, and the ideas just started flying out of my mouth. I ended up pitching him on a collectors’ edition set of four identical KISS covers, one for each of us. “The KISS fans will want to buy all four of them,” I said.

When the four solo covers of

Spin

came out, I brought them into rehearsals at Cobo Hall in Detroit, before our first performance, to show Ace and Peter that I was pushing the band, not myself. As long as I live, I’ll never forget Ace’s reaction. He picked up his solo

cover and said, “I fucking hate this. This sucks. I’m leaving the band.” And he walked out. He later came back calmer and explained that he didn’t like his photograph. By the end of the day, he was looking around and asking us if we really thought his picture looked okay. Subsequently I learned that Guccione had printed 60 percent Gene Simmons covers and 25 percent Paul Stanley covers. The remaining 15 percent was divided between Ace and Peter covers. It was not the equal printing everyone thought it was.

The first leg of our reunion tour lasted 193 shows and ran over two years. It was a triumph in every way. At the end of 1997, we were playing in New Jersey, and Dick Clark, ever the gentleman, asked us if we would ring in the new year. We had become the number one touring band. (Number two was our good friend Garth Brooks.) The reaction was so tremendous that for the millennium New Year’s Eve, Dick Clark decided to rebroadcast the footage.