Ladies in Waiting (34 page)

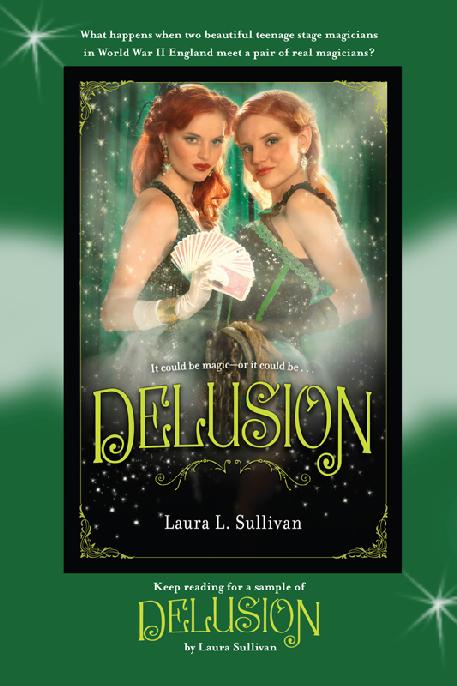

Authors: Laura L. Sullivan

She stood at Charles’s side and accepted the scalpel from his hand, hardly noticing when his fingers lingered on hers.

There’s a secret in there,

she thought, looking at Harry’s chest where lay the silent heart that once beat for her friend.

With Charles at her side, she made the first incision to delve within and ferret it out.

Chapter 1

Phil sprinted along the bank of the Thames, unbraiding her hair as she ran, so late she didn’t dare ask a passing stranger the time. Even that small delay might be disastrous. This was opening night.

She’d been doing clever bits of magic for a wounded soldier at the hospital as part of the Women’s Voluntary Service when she caught sight of his watch: six o’clock. With a hasty apology and a promise to return the next day to finish the trick, she dashed off to the Hall of Delusion. She didn’t know the soldier’s watch had stopped the moment the bombs first fell on his troop of the British Expeditionary Force in France, and that he kept it only as a memento.

Fee, dear Fee, was waiting for her when she slipped around the back of the theater. As always when they’d been apart any length of time, they embraced in their own peculiar way, forehead to forehead, leaning against each other, their long hair mingling in an alchemical blending. When they stood together like this—and they tended to linger, supporting and drawing support—they looked like a single creature. A magnificent portmanteau beast, said one of the old thespians who treated the Hall as his personal salon—a griffin, a chimera.

“I’m so sorry,” Phil whispered to her sister. “Do we have time to dress?”

“We have all the time in the world!” Fee said merrily, and revealed that it was only a little before five. “Time enough to draw a crowd.”

Phil groaned with the familial melodrama and separated herself from her sister. As always, they made a mutual soft murmur of regret that they must become their own unique selves again. With all that was going on in the world, they needed each other’s sisterly solace more than ever, but were so busy that they rarely had time simply to be together, as they had almost every moment in their earlier childhood.

Maybe there’ll be time tonight, when the show is over and everything is still,

Phil thought as she ran inside to change. There was so much for them to talk over.

When Phil came out, disguised, the sisters tossed a coin with Hector and Stan for who would be the busker and who would be the shill.

“I hate being the shill,” Phil said. “Anyway, by rights we shouldn’t have to do a thing but get in our costumes and gather our powers. It is

our

night, after all.”

“If we don’t have an audience, it won’t be much of a show,” Fee said, coaxing Phil down the steps and casting an angelic smile at the two orphan boys her family had informally adopted. “Besides,” she added, “they’re much better at close-up magic than we are.” They parted, going around opposite sides of the Hall of Delusion, the theater that had been in their family since the seventeenth century.

Phil might have preferred to sip tea (though not too much before going onstage, she’d learned the hard way) or, better yet, work out her nerves boxing with her brother, but she would never dream of shirking her duty—any duty. Her life, her calling, was the stage, but she had any number of lesser passions too, and she approached each of them with a single-minded dedication. Everything she did was, to her, the most important thing in the world, and she took herself, and her causes, very seriously.

She adjusted the severe lines of her dowdy wool suit.

Fancy, dressing like a spinster secretary at my age,

she thought. In addition to her inherited histrionics, she shared her family’s obsession with clothes and generally managed to wear something that sparkled, even in wartime. Phil was seventeen but was disguised that day as a forty-year-old, complete with faint painted crow’s-feet around her eyes. She came from a long line of performers and was ready to play anything from infant to sexpot to granny if it made the audience roar.

Now she looked respectable, practical, as ordinary as it was possible for her to look. A close observer might have noticed the lush curves that strained against the spare, rationed goods of her skirt, or the extravagance of flame-colored hair she’d tucked up under an efficient turban—she was most palpably made for the stage—but her family’s business relied on the public’s inability to closely observe anything, and Phil was, to the casual eye, just another pedestrian, one who would never believe in magic.

Which made it all the more impressive when this stodgy gray-clad secretary loudly exclaimed, “Merciful heavens, that fellow is flying!”

She let her mouth gape and her eyes bulge—an unattractive expression, but one she’d practiced at great length in front of a mirror. She looked like a codfish, but it got people to stop and share her amazement.

The instant she’d cried out, a young man in sprightly plus-fours who was apparently levitating a few inches in the air fell heavily to the ground with an apologetic grunt, as if to beg the public’s pardon for doing something as frivolous as floating when there was a war going on. No fewer than five people stopped and stared.

“It can’t be,” the disguised Phil said, shaking her head. “I must be seeing things.”

“What you are seeing, madam, is magic, pure and simple.”

“I don’t believe it,” she said, for there’s nothing more compelling than seeing a skeptic converted.

Another three people joined the gathering.

“Do it again,” Phil begged, then settled back to watch Hector work his magic.

“Take care, please,” he told a woman bending curiously to examine his shoes for wires or hydraulic lifts. He gave a self-deprecating little laugh. “I am only an apprentice, and sometimes I fall from the sky.”

A clever new touch,

Phil thought,

suggesting he could soar to the heavens if he trained a bit more.

If you lead someone to consider the impossible, they’re that much more likely to accept the merely improbable.

“And you, sir, with your fine watch, please step back a bit. The antigravitational forces are such as to occasionally disrupt timepieces.”

Phil nodded in approval. He had them positioned exactly right, clustered and facing traffic so the passing motors and pedestrians too single-minded to stop would create a blurring backdrop to the trick and add to the distraction. He turned so they looked at his heels from an angle, placed his feet just so, raised his hands with a flourish that brought all eyes but Phil’s briefly away from his feet, then, trembling with the mighty effort needed to control the forces of the universe, raised his entire body three inches off the ground.

Except, of course, for the toes of his right foot, which the astonished crowd couldn’t see.

Gravity pounced upon him again, and he landed with a stagger, out of breath and grinning. “Come back in a year and see how high I can go. Or you can see what a master magician can do this very afternoon.” He gestured to a brightly lit marquee that would be extinguished when blackout began at dusk.

“Experience the powers of the House of Albion, possessed of the secrets of the ages. This family of magicians has been at the royal command for four hundred years.” This was not strictly true. Legend had it that an Albion once cast Charles I’s horoscope, predicting a short life and a sore throat, and occasionally a prince and his entourage filled a box at the Hall, but they had no royal charter. “For mere pennies”—well, quite a few of them—“you too can see the wonders once reserved for kings and emperors. See the visible vanish and unseen spirits forced into flesh. See a man have his head sawed off, a woman drown and be reborn.” His voice had lapsed into a hawker’s dramatic wheedle, and he instantly lost half the crowd. They liked the show, but they didn’t want to be sold something.

That was careless of him, sounding like a carny at a fair. He knew his business better than that. Come to think of it, he was off his game in his levitation, too. He’d done the lazy version, not the more difficult—and much more impressive—variation that required clandestinely removing his shoe and picking it up between his heels while standing on his hidden bare foot. You could deceive a much larger crowd that way, and get better altitude.

She watched him awhile as he set up a little table and began card tricks. Again, he stuck to the most basic palmings and switches—and was so clumsy that Phil heard a little boy say, “Mummy, I see the queen in his pocket!”

Hector wasn’t an Albion, but he’d been training with the family for five years, since arriving as a scruffy twelve-year-old with a black-haired gypsy-looking boy in tow. He knew the business almost as well as those who had it in their blood, so it surprised Phil that he would put on such a ham-handed show.

Not that they needed to boost the audience that night. It was Phil and Fee’s debut, and their parents had called in every favor to fill the seats on their daughters’ most important night. It was a graduation of sorts—the first time they’d be performing an elaborate illusion entirely of their own device—and their parents were as nervous and proud as mother eagles watching their chicks’ maiden flight.

And now,

Phil thought,

I have something to distract me on the most important day of my life.

There was only one reason Hector would be dropping cards and losing his ace: he was planning to propose.

It was a logical match, and Phil was an eminently logical girl.

He’d been devoted to her since the day after showing up at the Albion doorstep, when she’d pulled a piece of chocolate from his ear and deigned to share it with him. At first she refused to teach him any magic tricks—they were family secrets, after all—but he managed to spy on them while earning his keep sweeping the aisles and scrubbing the loo, and one day he surprised them all with a quite passable transformation of a beetle into a flower. From that day on, he was allowed to sit in on magic lessons, and he attached himself particularly to Phil. He continued to spy on her, to ferret out the few spectacular illusions the family refused to teach him, but a year ago he let himself be caught, accepted Phil’s furious lecture, told her how lovely she was, and kissed her.

Hector’s courtship had progressed with increasing confidence, and Phil tolerated it with a good humor. At first, indeed, it was something of a joke, and when she curled up in bed with Fee every night, they’d giggle over his imbecilic love poetry and misguided attempts at gallantry. But—and maybe it was simply force of habit—she eventually stopped laughing and tentatively accepted his advances. They never progressed beyond kisses and a bit of pawing. Neither had time for much more than that, what with the theater and their studies under a tutor (who gave his services in exchange for the use of the venue every Tuesday to put on his avant-garde plays.)

As soon as he’d planted that first kiss, he began talking about their future together in such an assured manner that she didn’t quite have the heart to correct him. He was a dear friend—and she couldn’t kill a dear friend’s dreams. But when his dreams seemed to include her as his wife, she became uneasy.

Well, it’s only sensible,

she told herself.

I’m a magician, I mean to remain a magician, and I can’t see myself married to a greengrocer or publican. Magicians marry magicians, or at least entertainers.

Phil’s own heartrendingly beautiful mum had been an opera singer when she married Dad, but one stage is very like another, and she knew how to wear false eyelashes and take direction. Phil knew she would marry a magician and bear magician children, as her ancestors had for hundreds of years, and it was all very proper, very suitable, that she should marry Hector.

Then why does it put me off my game to even think of him proposing?

she wondered.

Because I don’t love him. I’m very fond of him. I always have a good time when I’m around him. We work well together. It would be an ideal marriage, without passion, perhaps, but who needs that? Leave that for Fee, who falls in love every ten days like very romantic clockwork.

So she told herself, but though she could generally convince anyone of anything when she set her mind to it (though it’s true they sometimes gave in from sheer weariness), Phil still had her doubts.

Hector was having difficulty holding the crowd’s interest, and he flashed her a subtle signal to help. But she was annoyed at his presumption to think of doing something so silly as proposing on her big night, so she abandoned him and drifted over to the cluster of people gathered around little Stan.

After all, Phil was a master of escape.

As if the buildings around the Hall of Delusion had been a pagan temple constructed to mark the passing of the seasons, there were a very few evenings of the year when the declining sun squeezed its molten light directly into the narrow crevice between the walls, casting the street in a buttery glow. The light seemed to seek out two objects: a haze of a girl in the softest red and gold, and a small dancing crystalline orb. The boy who manipulated the orb was himself in shadow. He carried the shadow with him, in his dark skin and hair, in his very being, as if he both cast his own darkness and hid in it. His opacity served as a foil for the brilliant glass ball he danced over and under his fingers, defying gravity as surely as Hector but without, as far as Phil could ever see, using any tricks. It was pure dexterity, the dint of countless hours of practice, and was in itself a kind of magic of concentration. The sun made opalescent fire flash in the clear glass as it floated over his knuckles, slipped between his fingers, and leaped up in the air, only to roll down his suddenly arched back and caper once more on his waiting fingertips.