Las Christmas (19 page)

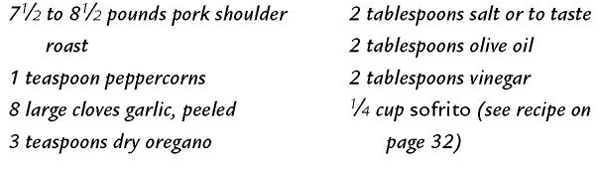

Pernil

ROASTED PORK

The

pernil

is the

lechón

you can't make. Rather than cooking a whole pig (the

lechón

), we cook only the meatiest part, the shoulder roast

(pernil)

, which can be easily divided into nice-size portions.

Wash and dry pork roast. Score meat all around with a sharp knife. Set aside.

Grind peppercorns, garlic, oregano, and salt in mortar and pestle until they form a paste. Add olive oil, vinegar, and

sofrito,

and mash until paste is smooth.

Rub

adobo

over the pork roast, making sure paste goes deep into slits. Place in shallow baking pan, cover tightly, and allow to marinate overnight.

Remove the pork from the refrigerator 30 minutes before cooking. Drain any liquid that may have formed overnight and pour over the pork.

Preheat oven to 300 degrees. Cook for 1 hour. Raise oven temperature to 350 degrees. Cook for another 2 hours or until internal temperature reaches 185 degrees.

Ilan Stavans

Ilan Stavans grew up in Mexico City. A nominee for the National Book Critics

Circle Award and the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Latino

Literature Prize, he teaches at Amherst College. His many books include

The Hispanic Condition (HarperPerennial), Art and Anger and The Riddle of Cantinflas

(both University of New Mexico Press),

Bandido: Oscar “Zeta” Acosta and the Chicano Experience (HarperCollins), and The Oxford Book of Latin American Essays.

OY! WHAT A HOLIDAY!

HANUKKAH IN DISTRITO FEDERAL was a season of joy. The weeklong festival of light was celebrated at home and in school and, indirectly, in our Gentile neighborhood where it was part of the season of

posadas.

Hanukkah almost always fell near Christmas, so many of my holiday memories blend Judas Maccabee with colorful piñatas filled with oranges,

colación,

and bite-sized pieces of sugar cane. In our Yiddish school, we performed humorous

schpiels,

re-enacting the plight of the Hasmoneans who waged a guerrilla war in Palestine in 165 B.C. when the Syrian ruler Antiochus IV desecrated Jerusalem's Holy Temple.

In my young mind, the Jewish resistance became confused with the sorts of uprisings orchestrated by South American left-wing

comandantes.

I pictured the Hasmoneans as Uzi-wielding freedom-fighters in army fatigues.

In one Yiddish-school Hanukkah

schpiel,

I played Judas's father, Mattathias of Modin, sporting a mock beard in the style of Fidel Castro. Another year, in the role of Antiochus, I wore a costume more Spanish conquistador than Old Testament warrior and tried to simulate the voice of Presidente Luis EcheverrÃa Alvarez as I pretended to conquer the Hebrew temple, which in our

schpiel

resembled the pyramid of the sun at Teotihuacán.

During Hanukkah, my parents would give my siblings and me a present each evening. I remember how thrilled I was to receive a beautiful

tÃtere,

a puppet of a humble campesino with a huge mustache, a bottle in one hand, and a pistol in the other. After we opened our gifts, my mother would light another candle in the menorah, placing the candelabra in the dining room window sill.

Our extended family sometimes gathered at my grandmother's house in Colonia Hipódromo for a Hanukkah feast. The cousins sat in circles playing dreidl, spinning the little top, and gambling on how it would fall. No matter how much I prayed for a miracle like the one that swept the Maccabees to redemption, I never managed to win, so that at the end of the evening I was left with no remaining assets to speak of and a bad temper.

After the game, my grandmother served her traditional Jewish-Mexican holiday menu:

pescado a la veracruzana,

chicken soup with

kneidlach,

oven-fried potato latkes topped with

mole poblano

and applesauce. Dessert attempted to evoke the baking style of Eastern European Jewry but were really closer to

tÃpico

Mexican

bizcochos.

Bellies already overloaded, we ended the evening by joining our neighbors in their

posadas.

Numerousâoften awkwardâtheological questions about the meaning of Judaism would arise.

“Why eight candles?” someone would ask.

“Well, it is because of a

milagro,

a miracle thatâ”

“Gosh, you guys believe in miracles? The only miracle that ever happened was the one that gave life to our Lord Jesus.”

Silence.

“Did you guys really kill Jesus Christ?”

Suddenly, my mind goes blank. “You mean us, personally?”

“Do you Jews consider Him the Messiah?”

“Do you know what the Immaculate Conception is?”

Searching for replies left me with a bizarre, uncomfortable aftertaste. Our Gentile friends never took our answers at face value. Their faces betrayed their puzzlement. No, we had not killed Jesus, nor did we consider him a Messiah but a prophet of biblical dimensions and a nationalistic one at that. Our neighbors accepted us; perhaps a few even loved usâbut clearly, they regarded us as creatures from another planet.

I only began to think of my Hanukkah celebrations as “exotic” when I emigrated to Manhattan and described these fiestas to my new American-Jewish friends, whose knowledge of the Hispanic world was limited to a couple of Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez novels and a weekend in Acapulco. While I was still a child, the thing that struck me most about our Jewish holidays was that they belonged not only to me, a Mexican Jew, but to an endless chain of generations. My parents and teachers had made me an integral part of a small, but transnational and multilingual cultureâabstract, marginal, dispersed in corners all over the globe. Millions of kids before me had spun the Hanukkah dreidl and millions more would do so in the centuries to come. I understood that I was just a bridge across an infinite stream. Like all Jewish children, I was a time-traveling Maccabee, re-enacting a cosmic festival of self-definition.

Pescado a la

Veracruzana

FILLET OF FISH IN A TOMATO AND ONION SAUCE

This recipe is a family heirloom, graciously sent to us from Mexico City by Ilan Stavan's family, in memory of his grandmother, Miriam Slominski (1912â1991), who prepared it. The dish, a classic of Mexican cuisine, gets its name from the Gulf Coast port city of Veracruz. The term

chile güero

is used for a variety of yellow peppers. Some are hotter than others. The pickled version, found in jars, is usually very mild. Two small fresh chiles give the sauce just a gentle kick. Taste it as it simmers and add more if you like a spicier dish. Simmer the sauce a bit longer if you have the time. After 30 or 40 minutes on the stove, the flavors merge delectably.

The fish

Lightly beat the eggs in a bowl with a fork. Dredge the fish fillets in the eggs, and then in the flour. Heat the oil in a sauté pan. Finely slice 2 of the onions and 4 of the garlic cloves, and sauté until they just begin to brown. Add the fish, and fry until it turns golden. Drain on paper towels until most of the oil has been absorbed.

The sauce

Slice the remaining onions and garlic cloves, the parsley, and the tomatoes. Chop in a blender or food processor briefly so that the mixture becomes a thick juice. Strain. Heat the strained juice in a saucepan, stirring. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat, add bay leaf, and simmer for 10 minutes. If the mixture becomes too thick, add a little water. Add the olives and sliced chiles. Cook 5 minutes more.

Add the fish to the sauce. Add salt and pepper to taste.

Allow the dish to sit for 5 minutes before serving.

Makes

6

servings

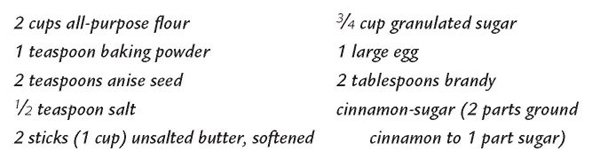

Bizcochitos

MEXICAN ANISE COOKIES

These traditional Mexican pastries are almost identical to an Eastern European Jewish cookie. The Jewish version substitutes poppy seeds for the anise. If you don't like the crunch of seeds in your cookies, you can flavor the sugar by mixing it with the anise. Let it stand overnight, then strain out the seeds before proceeding with the recipe.

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Mix the flour, baking powder, anise seed, and salt together in a bowl. Cream the butter and sugar together, add the egg, then the brandy, beating well. Gradually add the dry ingredients and mix well.

Form the dough into a large ball, wrap in plastic wrap, and refrigerate until coldâabout 2 hours. (Dough can be made ahead and kept refrigerated.)

Roll the dough out to about ¼ inch thick, and cut into shapes with a knife or cookie cutter. Bake until cookies begin to turn slightly goldenâabout 20 minutes. Allow to cool just until they can be removed easily from the cookie sheets, then remove onto a platter and sprinkle with cinnamon sugar.

Makes

about

2

dozen cookies