Last Night at the Circle Cinema (18 page)

Read Last Night at the Circle Cinema Online

Authors: Emily Franklin

The main theater was the original stage, back when the whole building was a single theater with movies accompanied by a live organist, the seats antiqued and not particularly comfortable. The management had tried for a retro-cool look, preserving the thick velvet curtain and the ornate metal wall decor, but had only succeeded in making the room look like a decrepit mental asylum.

As I approached the main door, I had to do a double take. I got to where I thought the entrance was, and there was a wall. Around the corner was another door, but when I got there, feeling along like I was trying to read braille, there was only more wall, more obsolete movie posters.

I remembered going to the anti-Oscars film fest the year before with Livvy and her friend, Marta. Bertucci had arrived halfway through, slipped into our row, and reached for popcorn like he'd been there all along. The Circle played the World's Worst Movies on Oscar day, colossal flops and laughable attempts that made the audience recite bad lines or howl with laughter.

“Let's move to the balcony,” Bertucci had suggested.

“No way,” Marta had said. She was Olivia's oldest friend, a fellow tennis player, very type A. “It's off-limits.”

“Nothing's off-limits,” Bertucci told her.

Olivia defended her friend. “Marta's rightâwe have good seats here.”

Bertucci tried again but we didn't end up moving. “I'm always afraid I'll fall off,” Marta whispered as the next movie started.

“Fair enough,” Bertucci had said.

Now I paced the theater wondering what was wrong with me until it hit me. “Senior Doorway!” I said and began pounding the walls for space or for a hollow sound, anything that would suggest that the doorway was underneath and merely hidden. “You're repeating yourself, Bertucci! Sloppy.”

But it wasn't sloppy. It took me a long time to find the seam, to wrestle the plywood piece from the wall in order to gain access to the theater. Inside, the theater's emergency lights were on but almost entirely faded, causing the already dilapidated room to look haunted.

Had we really sat there, laughing and eating popcorn at the anti-Oscars? Had we really worn costumes and done the

Princess Bride

Quote-Along, holding inflatable swords and chucking peanuts at the screen when the line called for it?

It was like everything that had come before was a different life that had happened to another person, only I was also aware that I was that person. Somewhere there was something that would connect that past and the present. My fingers squeezed the plastic CD cover hard enough that it snapped, creating a shard that sliced my hand. I winced and sucked the blood off, trying to muster the courage to take the hidden stairwell at the side of the theater.

I stepped onto the stairs, trying to ignore my anxiety. The sheer terror of being anywhere in the dark, not to mention in the dark alone, pulsed around me.

Why had I stepped away from Livvy again? What kept me from from holding her hand and pulling her up the dark stairwell with me? I stopped.

My palm stung. My legs felt both hollow and filled with concreteâunsteady but horribly weighted. I forced myself to go farther and opened the door. The first thing I saw was a stereo, all wired and, in case I was too blind to make it out in the half-light or too freaked out to function, there was an arrow and a note slapped on it. “CD goes here.”

I did as I was instructed and pressed play, listening to the first few songs, which Bertucci had deftly edited into 30-second samples. They brought back memories of flinging the Frisbee back and forth across Bertucci's scrubby backyard. Rap in German, pop in French, Sinéad O'Connor (“Hottest bald chick ever,” Bertucci had explained when he'd played her album

I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got

in full for us). Olivia had been into Elvis Costello; I could see her in the upstairs window looking adorable in a sundress, dancing, no doubt putting on an English accent.

Murder, pretending?

Now those lyrics weren't pop music but scary.

I skipped forwardâbreaking the rules of a mix as far as Bertucci was concernedâand found the Beatles. Good old reliable Beatles. I sat there, finding comfort in singing songs that I'd known forever, that my parents had played on Sundays while they read the paper. A song asked where did you go, and I tried to picture sitting at graduation, my butt on the hard folding chairs as they made speeches and handed out diplomas and people in the audience clutched their Kleenex. My mom would want to frame my diploma, and I'd probably let her, but it didn't mean that much. It was just paper. It couldn't possibly be the sum total of everything I'd done and experienced over the past four years. In fact, at this point, it seemed like a stupid marker.

I looked up and, with a start, saw Bertucci leaning against the projector wall, hand on top of it.

“Stop doing that,” I said, my voice wobbly and light. “Stop freaking showing up and scaring the crap out of me.”

He grinned and lip-synched, like a nonchalant, affable Nick Drake, all loose-limbed and graceful. Bertucci had perfect timing and terrible pitch and rarely sang out loud except in the shower. Livvy and I would sit there waiting for him sometimes, laughing at his tone-deaf version of “I'll Follow the Sun” or “Harvester of Sorrow” or whatever randomness appeared in his brain.

“Any thoughts about what I should say at graduation?” I asked him, though I knew Bertucci would give me nothing.

A couple of years before, I'd been stuck on my sophomore speech, the required five-minute talk each Brookville student had to give, and I'd begged him to help. He was the kind of guy who didn't write it, just ad-libbed a perfect five minutes on Simon and Garfunkel's song “The 59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin' Groovy)” as a philosophical statement. But he wouldn't give me ideas for topics or, once I'd chosen the Art of Contradiction (my Art of Contraception idea had been negged by my teacher), he didn't offer suggestions either.

Reductio ad absurdum

. Reduction to the absurd. I'd spoken of my own experience with it, the old parent-child convo: Why'd you cheat? All my friends were cheating. So if all your friends jumped off a bridge you'd do that?

Bertucci kept staring at me, miming the song.

“My sophomore speech sucked,” I said. “Everyone loved yoursâyou and your soundtrack.” I paused. “Oh my God. I am so thick. That's what this is, right?” I pointed to the CD. “This is the soundtrack of tonight?”

I thought I could see Bertucci nod in the darkness, the way he always had, not a full nod, more of a head flick. “What am I supposed to say tomorrow?” I asked again and sighed.

I thought of Olivia, of asking her. Why was I so afraid of it? In that balcony, I became aware that telling Olivia meant telling myself. That's what made it so hard.

I was expected to make a speech at graduation, and I wondered if maybe I should talk about “Feelin' Groovy,” the song that played right then. Probably not. Perhaps about how diplomas themselves are not eco-friendly. How probably tattoos are more appropriate. Not that I had any or wanted to get ink injected into my skin. But they were permanent and perhaps a better indicator of everything, a scar of some kind that would fade but never disappear.

26

Livvy

The music blasted so loud I figured the cops would show up any minute. I lived my life in constant fear I was doing something wrong, always second-guessing myself and my actions. That's how I felt about Codman and Bertucci. If I'd said something different to them, or opened up more, if I'd flung open some doors and closed others, would things be different?

The music kept coming, rolling over me in waves, and I could almost see Bertucci kneeling on the floor of Codman's room, flipping through the albums that Codman stored in old milk crates. There was an order to them, but I didn't know what it was. I was content to sit there not knowing, letting the guys pick songs or have them find the ones I wanted to hear. They both had an appreciation for vinyl. One I didn't share but didn't mind.

Bertucci, I realized, must have rigged up the entire sound system, coming to the Circle Lord knows how many times to set this up. Such preparation. Or maybe it was easier than I thought and Bertucci had connected a few wires, flipped a few switches, and prestoâinstant soundtrack.

I knew that's what it was from the second the notes piped out of the oversized white speakers that perched atop the metal beams near the ceiling.

This didn't mean I knew what to do.

In fact, I became convinced that leaving was the best option. Certainly I wasn't going to be able to talk to Bertucci about everything or tell Codman my real feelings in this context, so why stay?

Because I had showed up.

Because I could.

I felt rooted to the lobby, the cat coiled up on my belly as I sat on the floor eating my grainy bruised apple, waiting for a sign. How long had the cat lived here in the decrepit building? I pictured Bertucci bringing food. Had he checked on the cat regularly or left it to fend for itself? Cats could do that, I had heard, survive for long periods of time with very little to sustain them.

Not that I was big into signs, but I wanted somethingâanything that would give me direction.

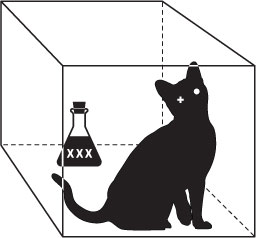

The cat purred. “What's the matter? You don't like French pop music?” I asked as I hummed. I half-expected the cat to answer. Maybe Bertucci had rigged that too. But Schrödinger didn't answer. I looked at the tag. Schrödinger.

“Oh, Schrödinger! I get it! You're the cat!”

I had sat that night on my bedroom floor, trying to wrap my head around the complexities that spewed from Bertucci's mouth. He pointed to his physics textbook and his handwritten notes that I teased him about but secretly found charming.

Codman and I had planned to go to my parents' beach house the next morning, cutting class for my first time ever to beat the Memorial Day weekend traffic.

“Are you sure you don't want to come?” I'd asked Bertucci. Codman wasn't there, and I worried that he was having second thoughts about coming with me; that, like me, he could easily picture the two of us, hand in hand on the beach, sharing a room at night, the triangle broken.

There were so many reasons for loving Codman: the way my gut ached after he'd make me laugh; how he told me stuff he never told anyone else; how nice he was to his parents even though they drove him crazy with their need to talk, talk, talk about feelings and drive and motivation; and how kind they were to him even though he fundamentally let them down on a regular basis. How he looked when the sun caught the tips of his hair as he played Frisbee. How he knew I was watching but didn't make fun of me for that, he just gave a wink I could see even from far away. How he'd cut soccer practiceâgetting benched for that week's gameâto bring me homemade banana bread when I was sick. Were there eggshells in a few bites? Yes, but still. Codman had a way of telling stories and putting his hand on my arm so firmly it felt like I was actually anchored to something. He was aware of his own faults, too, which was something else to love him for.

And yet I hated him for not showing that night, for that space on the floor beside me that should have contained Codman's jean-clad legs, his navy blue long-sleeved T-shirt pushed up to the elbows as he did when he was concentrating. But he wasn't there. It was me and Bertucci.

“Don't you want to join us?” I asked. “Road trip? Lobsters? Cookout? Beach?”

“Those are all good words,” Bertucci said, though his face was stony. “But no. You young folks cut class and head out. I appreciate the inviteâ”

“You don't have to be invited,” I said. Did he feel left out? Had I made it seem like a thing? Like it was a setup for me and Codman? Was it?

“I have plans of my own,” Bertucci had said, and he didn't sound wounded at all. Just matter-of-fact and monotone, the way he often did when he was in one of his depressive moods. He tapped the textbook in front of him.

Bertucci had gone through various equations, which made some sense though in a hazy way. Was I super interested in it all? Not really. A little, I guess. But he seemed so determined to have me get it, to know what he was explaining. His hands shook as he flipped the pages so I began doing it instead, which he interpreted as more interest on my part. Did I ask him why he was so nervous? No. And maybe I hated myself for that too.

“Erwin Schrödinger.”

“Oh, you know I love an umlaut,” I said, and Bertucci gave a smile that betrayed effort.

“So he's trying to demonstrate a sort of conflict between everything that quantum theory tells usâ”

“Which is?” I tried to get Bertucci to look at me or to take a chip from the bowl of sour cream and onion triangles I'd dumped in there, but he refused. He hadn't been eating much of anything lately, and even though the organic baked potato snacks were hardly appetizing, I hoped he would at least feign interest in them. He'd hardly touched the dinner I'd worked hard to make. It had occurred to me that maybe I had roasted the vegetables and made extra potatoes and greens in the hopes that Codman would show up in time to eat them, being instantly won over by my incredible cooking skills.

“Quantum theory is the theoretical basis of modern physics that explains the nature and behavior of matter and energy on the atomic and subatomic level.” Bertucci's gaze stayed on the text, but he seemed to slip away from me, from my room, from our conversation. I tapped his shoulder to bring him back. “What we are told about nature and behavior versus what we observe.”

“So, what we see might be different than what we think we know?” I asked. The textbook had a silly sketch of a cat inside a three-dimensional box.