Leonardo and the Last Supper (12 page)

Read Leonardo and the Last Supper Online

Authors: Ross King

There was a good reason why Castagno and Ghirlandaio, among others, interpreted the Last Supper—which the Gospels reveal to have been a mise-en-scène of agitation and puzzled astonishment—as a scene of tranquil reflection. Convents and monasteries were places of silence. The importance of silence was stressed in the cloister of San Marco, where the first image that greeted friars and visitors alike was Fra Angelico’s fresco of Peter of Verona with his finger to his lips. Silence was preserved in the cloisters, the church, and the dormitory. To keep the friars on their toes, each convent had an officer, the

circator

, whose job was to move quietly among the brothers “at odd and unexpected moments” to see if they were growing slack.

5

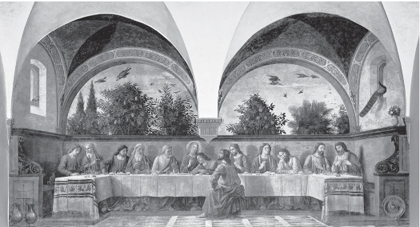

The Last Supper

by Domenico Ghirlandaio

The nuns enclosed in Sant’Apollonia inhabited this same world of silence and meditation, and the refectory where Castagno did his work was meant to be a still and quiet room. The rules observed by Benedictines stressed that meals in the refectory were to be taken in silence but for the voice of the person reading the sacred text: “During meals,” wrote Saint Benedict, “there should be complete silence disturbed by no whispering, nor should anyone’s voice be heard except the reader’s.”

6

Castagno probably showed a book-reading apostle (who wears a notably cross expression) as a reflection of the nun who would have been reading aloud to the other sisters. His quiet and pensive dinner table promoted the way the enclosed nuns of Sant’Apollonia were expected to behave both in the refectory and in their strictly cloistered lives more generally.

A Last Supper was never an easy proposition, even on spacious refectory walls. The artist had somehow to fit around a table thirteen separate figures through whom he would illustrate either the moment when Christ instituted the Eucharist or announced, to general incomprehension, that one of the number would betray him. Painters like Castagno and Ghirlandaio had created compelling scenes through a subtle choreography of hands and expressions, ones that duplicated the hushed and reflective mood prevailing in the refectories.

Leonardo, however, probably saw in these delicate gestures and gently furrowed brows few tokens of the exuberant life that he himself hoped to capture in his own art. He also would have glimpsed little of the drama that he would have read about in the Bible’s version of these events. The story is, after all, extraordinarily emotive. Thirteen men sit down to dinner to observe a solemn feast: a charismatic leader and his band of brothers, carefully selected and endowed with special powers. They are gathered in the middle of an occupied city whose authorities are plotting against them, waiting for their moment to strike. And in their midst, breaking bread with them, sits a traitor.

This was not a scene to which tapestries or stained-glass windows could do justice, or one that might provoke quiet and unruffled contemplation. Something else was called for.

Perhaps no one in history ever drew so much as Leonardo, or felt such a compelling need to record on paper everything he saw. His unrelenting activity was described by one source who claimed that whenever Leonardo went for a walk he tucked into his belt a little sketchbook in whose pages he could register “the faces, manners, clothes and bodily movement” of the people he saw around him.

7

Close observation of people going about their daily business—and then capturing their features and postures as accurately and realistically as possible—was essential to Leonardo’s art. In one of his notes he urged would-be painters to “go about, and constantly, as you go, observe, note and consider the circumstances and behaviour of men in talking, quarrelling or laughing or fighting together.”

8

The sight of an artist studying and sketching his fellow citizens in the marketplace or public square would have been quite unusual. Artists normally found models for their paintings in their own workshops, simply arranging their apprentices in the desired poses. Alternatively, they took postures and facial expressions from sculptures, from previous paintings, or from model books that helpfully provided details of how the body moved and looked in various poses. Leonardo, however, considered it an “extreme defect” for a painter to copy the poses or faces used by another artist.

9

He therefore took his studies out of doors and into the open air, where he could observe how real people moved and interacted.

For many years Leonardo had lived in a city—Florence—whose exuberant street life allowed him ample opportunity to witness this kind of stimulating activity. One of his contemporaries called Florence the “theatre of the world.”

10

Florentines gathered to socialize in the streets and piazzas, and on bridges such as the Ponte Vecchio. Songs and skits were performed in the open air during the Carnival, and in the piazzas teams of men, twenty-seven per side, played games of

calcio

, a violent and primitive version of football. Florence’s marketplace was a hive of activity. The poet Antonio Pucci described it as a world in itself, a place of spice merchants, butchers, moneylenders, ragmen, gamblers, and beggars. Also on the scene were female

vendors “who quarrel all day long...swearing badly / and calling one another whores.”

11

The other women to be seen in Florence’s streets were the whores themselves, who were required by law to wear long gloves, high-heeled slippers, bells on their heads, and a yellow ribbon.

One particular aspect of Florentine city life that seems to have intrigued Leonardo was the phenomenon known as the

sersaccenti delle pancacce

(know-it-alls of the benches).

12

These were the men from all walks of life who sat and gossiped on the many stone benches lining Florence’s streets, piazzas, and even the base of Giotto’s campanile and the facades of the great palazzos. One of the most prominent locations was the

ringhiera

, a stone platform (from which we get the word “harangue”) that was added to the Palazzo Vecchio in 1323 so the city fathers could address the populace. The discussions by the know-it-alls occupying these benches were sometimes impressively learned. The scholar and diplomat Giannozzo Manetti supposedly learned to speak Latin merely by eavesdropping on particularly erudite conversations, while men sitting on the benches in front of the Palazzo Spini once appealed to Leonardo for help explicating a passage of Dante. For the most part, though, the conversation was less edifying. A song from 1433 began: “Who wants to hear lies or little stories, come to listen to those who stay all day long on the benches.” Another writer lamented that the people on the benches were repositories of “envy and suspicion, enemies of all good.”

13

Leonardo was intrigued by the pictorial possibilities of Florence’s gossiping bench sitters. He must have walked through the streets, notebook in hand, watching the gestures and expressions of these men as they went about their “talking, quarrelling or laughing or fighting together.” He was fascinated with the interplay between and among people, such as when one person spoke and others listened: something he could have witnessed whenever speeches or announcements were made from the

ringhiera

. One of his memoranda considered how to depict a scene where one man addresses a group. “If the matter in hand be to set forth an argument,” he wrote, “let the speaker, with the fingers of the right hand hold one finger of the left hand, having the two smaller ones closed; and his face alert, and turned towards the people with mouth a little open, to look as though he spoke.” As for the audience, they should be “silent and attentive, all looking at the orator’s face with gestures of admiration,” with the older men depicted “sitting with their fingers clasped holding their weary knees” or else, with legs crossed, supporting their chins in their hands.

14

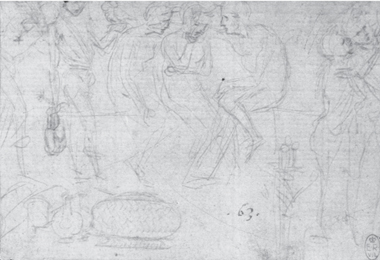

Leonardo’s sketches of men in public conversation in Florence

Leonardo reproduced these dynamics of speaking and listening in some of his sketches. In about 1480, around the time he began his

The Adoration of the Magi

, he made a small sketch of three figures seated on a bench. The trio’s postures are interesting. The man in the center, a

penseroso

, cups his chin in his right hand and his right elbow in his left hand, while two seated figures on either side lean close as if in commiseration; the man on the right puts a comforting arm around his downcast friend.

15

Similar drawings followed as he produced a series showing seated men in animated conversation striking casual and artless poses. Some of these might have been done as studies for his

Adoration of the Magi

, since all date from the early 1480s. Leonardo certainly planned a hubbub of movement and incident for his painting. His unfinished work shows an energetic jumble of figures tightly grouped in a horseshoe around the Virgin and Child: kneeling, clutching, contorting, and gesticulating as they press forward for a view.

As Leonardo made one of his sketches, another scene took shape in his mind. On the reverse of one of his drawings for figures in the

Adoration

he sketched several groups of figures, most seated and either listening or holding forth in conversation. Although some of these figures, too, may have been destined for the

Adoration

, Leonardo’s imagination took him elsewhere.

On the lower right-hand side of the page he loosely sketched five men sitting together on a bench. The man in the middle holds passionately forth, grasping the hand of one companion while thrusting a finger at another. His friends either listen intently, attempt to interrupt, or—in the case of the figure to his left—dreamily ignore him.

The scene is one Leonardo could easily have witnessed on the benches around Florence. But the act of drawing these seated figures in lively interaction appears to have sparked something in his mind. The lower left of the page features a lone figure, bearded and seated at a table, who is drawn to the same scale as the bench sitters. As he turns to his left he points to (or reaches for) a dish that sits in front of him. He is unmistakably a Christ figure, and the dish is unmistakably the one in which—as numerous other artists had shown before—Christ dips the sop he will give to Judas, identifying him as the betrayer. Leonardo’s animated bench sitters clearly reminded him of the apostles in a Last Supper.

By the early 1480s Leonardo therefore began examining—in no more than a few deft flicks of his quill pen—how he might show Christ and his apostles gathered around the table at the moment Christ announces the impending betrayal. His interest in the spirited exchanges meant the subject had a natural appeal to him, and the brio he gives their movements and expressions suggests that he wished to surpass the versions he had seen in Florence.