Leonardo and the Last Supper (33 page)

Read Leonardo and the Last Supper Online

Authors: Ross King

Pacioli’s arrival in Milan served to stimulate even more Leonardo’s keen interest in mathematics and geometry. He began filling his notebooks with multiplications and square roots. He praised the “supreme certainty of mathematics.”

33

Many hours were spent taking numbers to the power of three or four, dividing and subdividing geometrical figures, and involving himself in the age-old problem of “finding a square equal to a circle.”

34

So intense did these preoccupations become that they, rather than some catastrophic mishap or disconsolate realization about the impossibility of his designs, may have been responsible for temporarily curtailing Leonardo’s interest in flying machines. Coincidentally or not, Leonardo’s ambitions for flight began to languish the moment Pacioli arrived in Milan.

Yet the evidence for Leonardo’s interest in or use of divine proportion is scanty indeed. Nowhere in his notebooks did he mention or describe divine proportion: the concept can be found neither in his numerous comments on proportion nor in his even more voluminous notes on mathematics and geometry. Indeed, the complete absence of any reference to divine proportion is one of the surprises of Leonardo’s writings. If he believed divine proportion was indeed the key to beautiful design, something that had a universal applicability, why did he not mention it in his lengthy discussion of proportion in his treatise on painting?

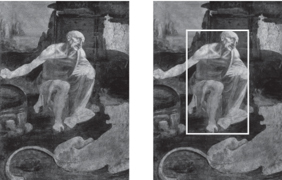

Nor can Leonardo’s paintings easily be adduced as evidence for experimentation with divine proportion. Geometric shapes can certainly be found in his paintings, as in the case of the equilateral triangle formed by Christ’s head and arms in

The Last Supper

. Moreover, rectangles created via the golden section may be imposed on some of the various faces in his paintings. The superimposition is, however, usually arbitrary and unconvincing. For example, a painting sometimes offered as proof is Leonardo’s unfinished

St. Jerome Praying in the Wilderness

, painted sometime in the 1480s. According to David Bergamini’s

Mathematics

, published in Time-Life’s wonderful “Science Library” series, the golden rectangle “fits so neatly around St. Jerome that some experts believe Leonardo purposely painted the figure to conform to these proportions.”

35

However, the visual evidence suggests, on the contrary, that the “experts” have purposely arranged the rectangle to conform (albeit imperfectly) to the figure of St. Jerome, whose arm extends well beyond this rectangular confinement and whose head is inconveniently below the upper perimeter. The theory is further troubled by the fact that Leonardo painted

St. Jerome Praying in the Wilderness

a decade before he met Pacioli and learned about divine proportion. The exercise recalls the efforts of the mathematician who, in the course of some doubtlessly pleasing research conducted during the 1940s, claimed to have discovered the golden section in the chest and waist measurements of Hollywood star Veronica Lake.

36

The reality is that the brilliance and appeal of Leonardo’s paintings have little to do with rectangles or measuring sticks and everything to do with astounding powers of observation and unsurpassed understanding of light, movement, and anatomy.

St. Jerome Praying in the Wilderness

takes its power from the profound contrast between the dazed and sinewy old hermit—in whom we see Leonardo’s fascination with the structural members of the human body—and the lithe torsion of the lion curled on the ground before him. This beast was no doubt drawn from life, modeled by one of the captive lions in the enclosure behind Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio, literally a few yards from his father’s house. Leonardo may even have dissected one of these lions at some point: “I have seen in the lion tribe,” one of his notes reads, “that the sense of smell is connected with part of the substance of the brain which comes down the nostrils, which form a spacious receptacle for the sense of smell.”

37

That kind of curiosity and dedication—a willingness to study the fierce creatures padding around their pens and then to peer inside their sectioned skulls—was the secret of Leonardo’s artistic genius, not a dedication to drawing rectangles.

Leonardo’s

St. Jerome Praying in the Wilderness

with rectangle imposed, exploring the supposed relationship of the painting to the golden section

One reason why Leonardo did not use divine proportion in his works (or advocate it in his writings) is that Pacioli himself did not actually promote it as a design template for painters and architects. That is, Pacioli did not champion divine proportion as the key to perfect design: indeed, the thought never seems to have occurred to him. He advocated instead the Vitruvian system: one based not on the irrational mathematical constant 1.61803 but rather on simple ratios (Vitruvius believed

10

to be the “perfect number”).

38

Leonardo trusted empirical study far more than abstract concepts. He was more inclined to believe his own eyes and a set of calipers than one of Plato’s pronouncements on the shape or proportions of the universe. Like Niccolò Machiavelli, he was interested in “things as they are in a real truth, rather than as they are imagined.”

39

He could have known from his measurements of Trezzo and Caravaggio that one widespread modern notion about the golden section—that if you divide your height by the distance

from your navel to the floor you get 1.61803—was demonstrably incorrect. Indeed, the height versus navel measurements of his

Vitruvian Man

(sometimes held out as bodily evidence of the golden section) yield a ratio of approximately 1.512, a good deal short of this universal ideal—and a perfect example of the sort of fudging required by so many theories about the artistic use of the golden section. Leonardo’s more empirical approach to human proportion led him to state ratios in other terms, using round numbers. Typical of his method was his claim that a man’s height equals eight times the length of his foot, or nine times the distance between his chin and the top of his forehead.

40

Or, as we have seen in the case of

The Last Supper

, he was interested in the application of tonal intervals to painting and architecture, using ratios such as 1:2, 2:3, and 3:4 to organize the architectural components of the room where Christ and the apostles sit.

Leonardo would have been mesmerized by the various manifestations of the golden section in the natural world: in the phyllotaxis of sunflowers, for example, whereby the florets in the seed head are configured in two opposing spirals, which always happen to be consecutive Fibonacci numbers: 21, 34, 55, 89, or 144 running clockwise versus, respectively, 34, 55, 89, 144, or 233 running counterclockwise. But Leonardo and his contemporaries, including Pacioli, were completely unaware of these manifestations, most of which were not discovered until the first half of the nineteenth century. Only in the first decades of the twentieth century—thanks to the Bauhaus designers as well as American painters such as Robert Henri and George Bellows—did the golden section actually enter the studios of artists and architects.

A few months after Luca Pacioli arrived in Milan, his collaborator and new friend abruptly vanished. In the summer of 1496, after some eighteen months of work at Santa Maria delle Grazie, Leonardo abruptly downed tools and left Milan. On 8 June, one of Lodovico Sforza’s secretaries reported that the artist had “caused a decided scandal, after which he left.”

41

The exact details of this scandal are not known. It may have involved a dispute over payment. Or perhaps Il Moro was losing patience with his tardy painter (who was perhaps spending more time on Pacioli’s polyhedra and less on the apostles) and urging him to finish. The scandal and the ensuing flight must have served to enhance Leonardo’s reputation as a willful

and difficult artist. It also meant that

The Last Supper

, like so many of his other works, was in danger of being abandoned unfinished.

For want of the original contract, we know none of the details about the commissioning, such as how much Leonardo was to be paid for

The Last Supper

or when he was supposed to finish. Reports about payments tend to vary widely. A friar at Santa Maria delle Grazie in the middle of the next century claimed Lodovico paid Leonardo an annual salary of five hundred ducats. This sum would have been substantial considering that the salary of high-ranking government officials was three hundred ducats, but it was hardly likely to keep Leonardo, with his expensive wardrobe and his entourage of servants and apprentices, in the lavish style to which he aspired. Matteo Bandello put Leonardo on a salary of two thousand ducats, which certainly would have kept him in lavish style.

42

Bandello was probably exaggerating and he may not have had access to the facts (he was only ten years old when Leonardo began work). However, it is plausible that Leonardo was paid two thousand ducats for the entire job of painting in the refectory. That was the exact amount paid to Filippino Lippi a few years earlier when he frescoed the Carafa Chapel in Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome.

43

A few years later, Michelangelo would receive three thousand ducats for frescoing the vault of the Sistine Chapel, a much larger commission.

Two thousand ducats—if that were indeed his payment for

The Last Supper

—was a substantial amount. It would have been sufficient, for example, for Leonardo to purchase a grand house beside the Arno in Florence.

44

It is tricky to translate two thousand ducats into today’s money. However, the ducat was composed of 0.1107 troy ounces (3.443 grams) of gold, which means that Leonardo (if Bandello is correct) received a total of 221.4 ounces of gold. Translated into today’s prices, with gold at $1,600 per ounce, Leonardo would have received the equivalent of a little more than $350,000.

Given Leonardo’s apparently generous remuneration, one wonders if the artist was unhappy with certain other circumstances. His frustration and indignation may have stemmed from the myriad of smaller tasks assigned to him by Lodovico. Like the monks of San Donato a Scopeto, who got Leonardo to paint a sundial for them while he was working on his

Adoration of the Magi

, Lodovico regarded his resident painter as a journeyman to whom he could prescribe, on a whim, the most menial and uninspiring tasks. If Beatrice required new plumbing for her bathroom, or if her bedchamber needed a new coat of paint, Leonardo was conscripted into service. The

duchess’s bedchamber may well have caused the breach, since Leonardo was painting her rooms in the Castello when he stormed off the job.

It is unclear if at this point Leonardo simply left the Castello or whether his fit of high dudgeon compelled him to flee Milan altogether. If he did leave Milan, one possibility is that he went to Brescia, in Venetian territory forty miles east of Milan. His presence in Brescia is undocumented, but it appears that he hoped to secure work painting an altarpiece for the Franciscan church of San Francesco. Thanks to Luca Pacioli, he knew the general of the Franciscan Order, Francesco Nani. Leonardo had sketched Nani’s portrait earlier in the year, and he may have gone to Brescia in the hope that the powerful ecclesiastic, whose family came from the city, would help pull strings to secure him the altarpiece commission.

45

Leonardo’s brief description of the proposed altarpiece makes it sound like a fairly traditional work. He planned to feature the Virgin Mary and Brescia’s two patron saints, Faustino and Giovita. The Virgin was to be elevated, probably on a throne, and the trio would be surrounded by an ensemble cast of Franciscan worthies, such as St. Francis, St. Bonaventure, St. Clare, and St. Anthony of Padua. The design (no doubt dictated by the Franciscan friars) is eerily reminiscent of the kind of work—such as the altarpiece for the chapel of San Bernardo in the Palazzo della Signoria—that he had left behind, unfinished, in Florence. How he could have summoned much enthusiasm for these figures after the dramatic mural he was in the midst of creating in Milan is difficult to imagine.