Liars and Outliers (28 page)

Read Liars and Outliers Online

Authors: Bruce Schneier

Large corporations can also play one societal dilemma off another. Remember our sandwich seller in the market. He's stuck in a societal dilemma with all the other sandwich sellers, and has to set his prices accordingly. In order to prevent the market's sandwich sellers from cooperating, society as a whole—as part of a larger societal dilemma—passes laws to prevent collusion and price-fixing. But a larger sandwich seller has more options. He can expand his product offering across several dimensions:

- Economies of scale

. He can buy his ingredients in bulk and streamline his production processes. - Depth

. More sandwich options. - Size

. Larger or smaller sandwiches. - Time

. Breakfast sandwiches or sandwiches for midnight snacks. - Scope

. Sandwich-like things, such as hot dogs, bagels, wraps, and muffins. - Accessories

. Chips and sodas, groceries. - Service

. Sandwich subscriptions, delivery, free wi-fi to go along with the sandwiches.

All this makes it much more difficult to enforce the basic societal dilemmas of a market economy. On the face of it, as a seller diversifies, he is now stuck in multiple different societal dilemmas: one with the other sandwich sellers in the market, and another with—for example—chip sellers. But by tying the two products together, perhaps selling a sandwich and chips together, or offering a once-a-week chip subscription with the purchase of a sandwich subscription, he is able to play the two societal dilemmas off each other, taking advantage of both.

We see this with various product schemes. Whether it's Citibank selling credit cards and consumer loans and anti-theft protection plans to go with those credit cards; or Apple selling computer hardware and software; or Verizon bundling telephone, cable, and Internet; product bundles and subscription services hide prices and make it harder for customers to make buying decisions. There's also a moral hazard here. The less Citibank spends on antifraud measures, the more protection plans it can sell; the higher its credit card interest rates, the more attractive its consumer loans are.

Large corporations can also use one revenue stream to subsidize another. So a big-box retail store can temporarily lower its prices so far that it's losing money, in order to drive out competition. Or an airline can do the same with airfares in certain markets to kill an upstart competitor.

Things get even more complicated when sellers have multiple revenue streams from different sources. Apple sells iPhones and iPads to customers, sells the ability to sell customer apps to app vendors, and sells the right to sell phone contracts to phone companies. Magazines sell both subscriptions and their subscription lists. This sort of thing is taken to the extreme by companies like Facebook, which don't even charge their users for their apps at all, and make all their money selling information about those users to third parties.

18

It turns out that offering a product or service for

free is very different

than offering it cheaply, and that “free” perturbs markets in ways no one fully understands. The optimal way to do business in an open-air market—offer the best products at the lowest prices—fails when there are other revenue streams available.

An additional complication arises with products and services that have high barriers to entry; it's hard for competitors to emerge. In an open-air market, if the sandwich vendors all sell their sandwiches at too-high prices, someone else can always come in and start selling cheaper sandwiches. This is much harder to do with cell phone networks, or computer operating systems, or airline tickets, because of the huge upfront costs. And industries can play the meta-game to prevent competition, as when the automobile industry bought and then dismantled cities' trolley networks, big agriculture lobbied government to impose draconian regulations on small farms, and so on.

There's one more problem with the technological corporations that doesn't really exist on the small scale of an open-air market: the risks of defection can be greater than the total value of the corporations themselves. An example will serve to explain.

Chemical plants

are a terrorism risk. Toxins such as phosgene, chlorine, and ammonia could be dispersed in a terrorist attack against a chemical plant. And depending on whose numbers you believe,

hundreds of plants

threaten hundreds of thousands of people and some threaten millions. This isn't meant to scare you; there's a lot of debate on how realistic this sort of terrorist attack is right now.

In any case, the question remains of how best to secure chemical plants against this threat. Normally, we leave the security of something up to its owner. The basic idea is that the owner of each chemical plant best understands the risks, and is the one who loses out if security fails. Any outsider—in this case, a regulatory agency—is just going to get it wrong.

And chemical plants do have security. They have fences and guards. They have computer and network security. They have fail-safe mechanisms built into their operations.

19

There are regulations they have to follow.

The problem is

that might not be enough. Any rational chemical-plant owner will only secure the plant up to its value to him. That is, if the plant is worth $100 million, it makes no sense to spend $200 million on securing it. If the odds of it being attacked are less than 1%, it doesn't even make sense to spend $1 million on securing it. The math is more complicated than this, because you have to factor in such things as the reputational cost of having your name splashed all over the media after an incident, but that's the basic idea.

But to society, the cost of an actual attack could be much, much greater. If a terrorist blows up a particularly toxic plant in the middle of a densely populated area, deaths could be in the tens of thousands and damage could be in the hundreds of millions. Indirect economic damage could be in the billions. The owner of the chlorine plant would pay none of these costs; to him, they are externalities borne by society as a whole.

Sure, the owner could be sued. But he's not at risk for more than the value of his company, and the outcome of a lawsuit is by no means preordained. Expensive lawyers can work wonders, courts can be fickle, and the government could step in and bail him out (as it did with airlines after 9/11). And a smart company can often protect itself by spinning off the risky asset in a subsidiary company, or selling it off completely. Mining companies do this all the time.

The result of all this is that, by leaving the security to the owner, we don't get enough of it.

In general, the person responsible for a risk trade-off will make the trade-off that is most beneficial to

him

. So when society designates an agent to make a risk trade-off on its behest, society has to solve the principal–agent problem and ensure that the agent makes the same trade-off that society would. We'll see how this can fail with government institutions in the next chapter; in this case, it's failing with corporations.

Think back to the sandwich sellers in the local market. Merchant Alice is one of those sandwich sellers, and a dishonest, unscrupulous one at that. She has no moral—or reputational—issues with potentially poisoning her buyers. In fact, the only thing that's standing in the way of her doing so is the law. And she's going to do the math.

She has the opportunity of making her sandwiches using some substandard but cheaper process. Maybe she's buying ingredients that aren't as clean. Whatever she's doing, it's something that saves her money but is undetectable by her customers.

If her increased profit for selling potentially poisonous sandwiches is $10,000, and the chance of her getting caught and fined is 10%, then any fine over $100,000 will keep her cooperating (assuming she's rational and that losing $100,000 matters to her).

Now consider a large sandwich corporation, ALICE Foods. Because ALICE Foods sells so many more sandwiches, its increased profit from defecting is $1,000,000. With the same 10% probability of penalty, the fine has to be over $10,000,000 to keep it from defecting. But there's another issue. ALICE Foods only has $5,000,000 in assets. For it, the maximum possible fine is everything the corporation has. Any penalty greater than $5,000,000 can be treated as $5,000,000. So ALICE Foods will rationally defect for any increased profit greater than $500,000, regardless of what the fine is set at (again, assuming the same 10% chance of being fined and no semblance of conscience).

Think of it this way. Suppose ALICE Foods makes $10,000,000 a year, but has a 5% chance of killing lots of people (or of encountering some other event that would bankrupt the company). Over the long run, this is a guaranteed loss-making business. But in the short term, management can expect ten years of profit. There is considerable incentive for the CEO to take the risk.

Of course, that incentive is counteracted by any laws that ascribe personal liability for those decisions. And the difficulty of doing the math means that many companies won't make these sorts of conscious decisions. But there always will be some defectors that will.

This problem occurs more frequently as the value of defecting increases with respect to the total value to the company. It's much easier for a large corporation to make many millions of dollars through breaking the law. But as long as the maximum possible penalty to the corporation is bankruptcy, there will be illegal activities that are perfectly rational to undertake as long as the probability of penalty is small enough.

20

Any company that is too big to fail—that the government will bail out rather than let fail—is the beneficiary of a free insurance policy underwritten by taxpayers. So while a normal-sized company would evaluate both the costs and benefits of defecting, a too-big-to-fail company knows that someone else will pick up the costs. This is a moral hazard that radically changes the risk trade-off, and limits the effectiveness of institutional pressure.

Of course, I'm not saying that all corporations will make these calculations and do whatever illegal activity is under consideration. There are still both moral and reputational pressures in place that keep both individuals and corporations from defecting. But the increasing power and scale of corporations is making this kind of failure more likely. If you assume that penalties are reasonably correlated with damages—and that a company can't buy insurance against this sort of malfeasance—then as companies can do more damaging things, the penalties against doing them become less effective as security measures. If a company can adversely affect the health of tens of millions of people, or cause large-scale environmental damage, the harm can easily dwarf the total value of the company. In a nutshell, the bigger the corporation, the greater the likelihood it could unleash a massive catastrophe on society.

Chapter 14

Institutions

In talking about group interests and group norms, I've mostly ignored the question of who determines the interests, sets the norms, and decides what scope of defection is acceptable and how much societal pressure is sufficient. It's easy to say “society decides,” and from a broad enough viewpoint, it does. Society decides on its pair-bonding norms, and what sorts of societal requirements it needs to enforce them. Society decides how property works, and what sorts of societal pressures are required to enforce property rights. Society decides what “fair” means, and what the social norms are regarding taking more or doing less than your fair share. These aren't deliberate decisions; they're evolved social decisions. So just as our immune system “decides” which pathogens to defend the body against, societies decide what the group norms are and what constitutes defecting behavior. And just as our immune system implements defenses against those pathogens, society implements societal pressures against what it deems to be defection.

But many societal pressures are prescribed by those in power,

1

and while the informal group-consensus process I just described might explain most moral and reputational pressure, it certainly doesn't explain institutional pressure. Throughout most of our history, we have been ruled by autocrats—leaders of family groups, of tribes, or of people living in geographical boundaries ranging in size from very small to the Mongol Empire. These individuals had a lot of power—often absolute power—to decide what the group did. They might not have been able to dictate social norms, but they could make and enforce laws. And very often, those laws were immoral, unfair, and harmful to some, or even most, people in the group.

Throughout most of our history, people had no say in the laws that ruled them. Those who ruled did so by force, and imposed laws by force. If the monarch in power decided that the country went to war, that's what the people did. The group interest was defined by what the king wanted, and those who ignored it and followed some competing interest were punished. It didn't matter if the majority agreed with the king; his word defined the group norm.

“L'État, c'est moi”

and all.

2

I'm eliding a lot of nuance here. Few rulers, from tribal leaders to emperors, had—or have—absolute power. They had councils of elders, powerful nobles, military generals, or other interests they had to appease in order to stay in power. They were limited by their roles and constrained by the societies they lived in. Sometimes a charismatic and powerful ruler could radically change society, but more often he was ruled by society just as much as he ruled it. Sometimes group norms are decided by privileged classes in society, or famous and influential people, or subgroups that happen to be in the right place at the right time.

In parts of our history, laws and policy were decided not by one person but by a cohort: the ancient Roman Senate, the

Maggior Consiglio

in medieval Venice, the British Parliament since the Magna Carta. Modern constitutional democracies take this even further, giving everybody—more or less—the right to decide who rules them, and under what rules those rulers rule.

This dynamic isn't limited to government; it also plays out in other groups. Someone in charge decides what the group's norms are, constrained by the “rules” of his office. A CEO can be removed from office by the board of directors. A Mafia head can be deposed by a rival; criminal gangs and terrorist groups have their own organizational structures.

The deciders generally don't decide the details of the norms and societal pressures. For example, while the king might decide that the country will go to war and all able-bodied men are to be drafted into the army, he won't decide what sorts of security measures will be put in place to limit defectors. Society delegates the implementation of societal pressures to some subgroup of society. Generally these are institutions, which I'll broadly define as an organization delegated with implementing societal pressure. We've already discussed delegation and the principal–agent problem. We're now going to look at how that plays out with institutions.

In 2010,

full-body scanners

were rushed into airports following the underwear bomber's failed attempt to blow himself up along with an airplane. There are a lot of reasons why the devices shouldn't be used, most notably because they can't directly detect the particular explosive

the underwear bomber

used, and probably wouldn't have detected his underwear bomb. There have been several court cases brought by people objecting to their use. One of them, filed by the Electronic Privacy Information Center, alleged the TSA didn't even follow its own rules when it fielded the devices. (Full disclosure: I was a plaintiff in that case.) I want to highlight an argument a Department of Homeland Security lawyer made in federal court. He contended that the agency has the legal authority to

strip-search every

air traveler, and that a mandatory strip-search rule could be instituted without any public comment or rulemaking. That is, he claimed that DHS was in charge of airline security in the U.S., and it could do anything—

anything

—it wanted to in that name.

After the

September 11 attacks

, people became much more scared of airplane terrorism. The data didn't back up their increased fears—airplane terrorism was actually a much larger risk in the 1980s—but 9/11 was a huge emotional event and it really knocked people's feeling of security out of whack. So society, in the form of the government, tried to improve airport security. George W. Bush signed the Aviation and Transportation Security Act on November 19, 2001, creating the Transportation Security Administration.

| Societal Dilemma: Airplane terrorism. | |

| Society: Society as a whole. | |

| Group interest: Safe air travel. | Competing interest: Blowing up airplanes is believed to be an effective way to make a political point or advance a political agenda. 3 |

| Group norm: Not to blow up airplanes. | Corresponding defection: Blow up airplanes. |

| To encourage people to act in the group interest, society implements these societal pressures: Moral: Our moral systems hold that murdering people and destroying property is wrong. Reputational: Society punishes people who kill innocents, and even people who espouse doing that. In some cases, people are publicly vilified not because they themselves advocate violence, but because they aren't sufficiently critical of those who do. Institutional: Nation states implement laws to fight airplane terrorism, including invasive passenger screening. We have severe punitive measures to deter terrorists, at least the non-suicide kind. Security: Magnetometers, x-ray machines, swabs fed into machines that detect potential explosives, full-body scanners, shoe scanners, no-fly lists, behavioral profiling, and on and on. |

The societal dilemma of airplane terrorism is a particularly dangerous one, because even a small number of defectors can cause thousands of deaths and billions of dollars in economic damage. People are legitimately concerned about this, and want strong societal pressures.

4

Moral and reputational pressures aren't nearly enough, both because the

scale is too large

and the competing group interest is so strong. Institutional pressure is required, and the institution in the U.S. that has been delegated with this responsibility is the Transportation Security Administration.

There are actually several levels of delegation going on. The people delegate security to their leaders—Congress and the president—who delegate to the Department of Homeland Security, which delegates to the TSA, which delegates to individual TSA agents staffing security checkpoints.

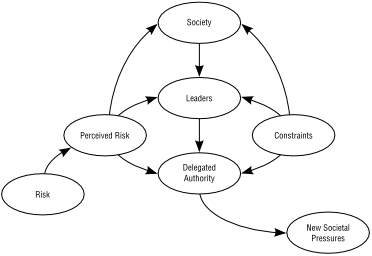

Figure 12

illustrates how institutional pressure is delegated. Ultimately, institutions are put in charge of enforcement. These aren't always governments; they can be any subgroup of society given the power to enforce institutional pressure at any level, such as:

- The police, who implement societal pressures against a broad array of competing norms. (Okay, I admit it. That's an odd way to describe arresting people who commit crimes against people and property.)

- The judicial system, which 1) punishes criminals and provides deterrence against future defections, and 2) adjudicates civil disputes, providing societal pressures based on both formal and informal societal norms.

- Government regulatory agencies, such as the U.S.'s TSA, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the Federal Communications Commission, and the Food and Drug Administration.

- Industry organizations, which implement industry self-regulation. (This is often agreed to in order to forestall government regulation.)

- Corporate security offices, which implement the physical and data-security policies of a corporation.

- Corporate auditors, who 1) verify the same, and 2) verify the corporation's books, providing societal pressures against corporate financial malfeasance.

- An independent security company, hired by an organization to guard its buildings.

Figure 12:

How Societal Pressures Are Delegated

The goal of delegation is for the institution to act as the group's agent. That is, to implement societal pressures on behalf of, and in the name of, the group. But because of the principal–agent problem, that institution doesn't have the same competing interests as the group as a whole—or even as any institution or subgroup above them. As a result, it won't necessarily implement societal pressures to the same degree or in the same way as the group would like. And that's an endless source of problems.

When it comes to terrorism and airplane security, those problems are legion. The TSA is a government institution with a mandate and funding from the U.S. government. It answers to the government. And the government has a mandate from, is funded by, and answers to, the people. Given all of that, you'd expect the people to have a lot of input into what the TSA does. Which is why it can seem so weird when it does things with absolutely no input from anyone. But it's a natural effect of the principal–agent problem.

The TSA's interests aren't the same as those of any of the groups it's an agent for: DHS, the government, or society as a whole.

For one, the TSA has a self-preservation interest. If it is seen as unnecessary—that is, if society as a whole believes there's a sufficiently diminished terrorist threat—it might be disbanded. Or perhaps its function would be taken over by some international security organization. In either case, like a person, the TSA is concerned about its own survival. (By the way, people working within the TSA are also concerned about their jobs, power, and reputation within the agency, and so on.)

For another, the TSA is concerned with its own reputation in the eyes of society. Yes, it wants to do a good job, but it also needs to be

seen

as doing a good job. If there's a terrorist attack, the TSA doesn't want to be blamed for not stopping the terrorists. So if a terrorist bombs a shopping mall instead of an airplane, it's a win for the TSA, even though the death toll might be the same.

5

Even without an actual terrorist attack, if it is seen as doing a bad job—even if it's actually doing a good job—it will be penalized with less public support, less funding, and less power.

6