Lilla's Feast (25 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

This time, the treaty-port residents were worried. They fled as Nationalist troops approached, not from fear of any direct attack upon themselves, but because they had no desire to be caught in the cross fire between the Nationalists and the local warlords. And in late March 1927, as the Nationalists neared the city, the treaty-port powers amassed the Shanghai Defence Force. With it came Toby Elderton.

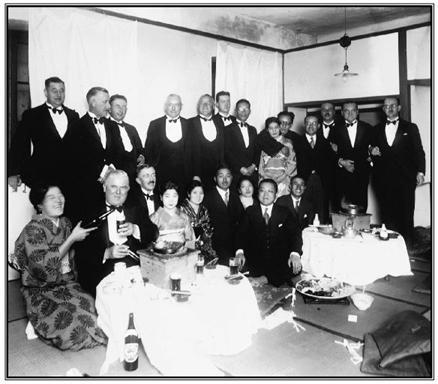

Toby and his “wives,” Chefoo, 1928. Lilla is on the left.

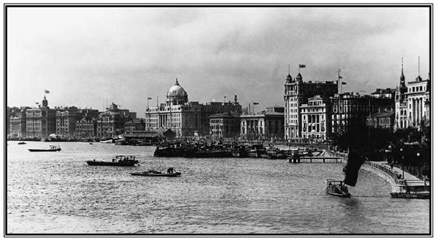

The waterfront, Shanghai

As Toby was saluted into the Shanghai harbor on the prow of a battleship, Ada and her two children, Alan and Betty, left England to join him. Lilla raced to catch up. She wasn’t going to let Ada go back to China without her. Not when she was traveling in such glory, with Toby at her side. By the time Ada and Toby arrived in Chefoo for a visit, Ada’s photographs show Lilla already there and with a brand-new man on her arm. She’d met him through her eldest brother Vivvy, and his name was Ernest Casey. He was one of the richest businessmen living in Chefoo and “a sweet old thing.” He was unmarried, had no children and no relatives to look down on Lilla. In any case, he was far from grand. He wasn’t even second- or third-generation treaty port. He’d simply pitched up out of nowhere and made his fortune himself.

Casey—everyone called him that—was smitten. Lilla dragged him around with Ada and Toby, naughtily flirting with both men as if to show that she could keep up with Ada and have a husband, even Ada’s husband, too. Toby took the bait and put an arm around each twin and called them “my wives,” raising a few eyebrows. Ada stood there, buttoned up in a double-breasted jacket that resembled an ill-fitting uniform, looking uncomfortable with her twin’s more open sexuality.

Casey asked Lilla to marry him. Lilla said maybe. And added him to her list of pen pals as she turned on her heels and left.

By the end of the 1920s, the place to go was France. The northeast of the country was still hopelessly trench-scarred, but although the postwar economic boom was running out of steam and the American stock market on Wall Street was crashing, on the Riviera, it was said, the ladies were painting their toenails red. Ada and Toby announced that they were taking their two happy, healthy, nearly grown-up children, Alan and Betty, on a driving tour of the country. Lilla packed Arthur into an equally smart car and persuaded Vivvy and his wife, Mabel, to match Ada’s party of four. Vivvy and Mabel were over from China, “spending money like water,” and throwing parties at the Ritz. The two groups met in Antibes—the twins, now forty-seven, wearing identical hats, driving identically shiny cars, each with three people in tow. Ada was keen to be off with her family. Lilla pretended to be too occupied with her party to care. When they returned, she encouraged Arthur to paste together a commemorative album of their trip, to show how grand it had been.

Then Lilla stumbled again. Arthur had followed his father into the army, where he was employed to hunt three days a week, compete in horse trials on another, and attend grand parties on the weekends. At one of these, he fell for a girl dubbed the Princess of the City by the gossip columns, the scion of a prominent industrial family who accompanied her father around town. Her name was Beryl Bowater. She was a dashing huntswoman and lived with her parents and a multitude of servants in a magnificent house in Chester Square, at the heart of Belgravia, still London’s most expensive residential address. Arthur was a handsome man, with regular features, sandy hair, and a twinkle in his bright blue eyes. He rode like a centaur and had even won an army boxing championship. And Beryl fell for him, too.

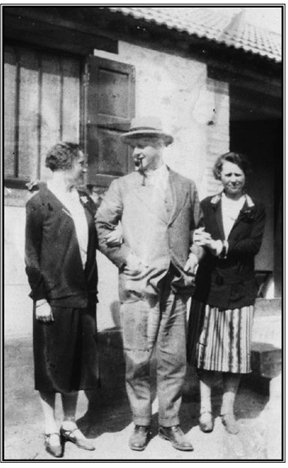

Vivvy, Lilla, and Mabel on the road to Paris

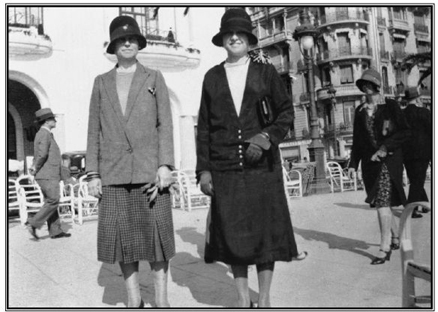

Lilla and Ada in Antibes, 1929. Lilla is on the right.

Although Arthur was encouraged by Beryl, his first attempt to raise the question of marriage with her father, Sir Frank, was met with ridicule. “You couldn’t afford to keep her in silk stockings,” he bellowed, kicking him out of the house.

Indeed he couldn’t. Compared to the Bowaters, Arthur was penniless.

Beryl pleaded with Arthur to try again. She pleaded with her father. How could he deny his darling daughter what she wanted?

The wedding was in London, in April 1931, in the grand church of St. Margaret’s, Westminster, which nestles between Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament. It’s a strange place to marry, as the crowds of tourists outside assume that they are watching some kind of royal wedding—some of the Royal Family do marry there—and line up along the paths to cheer in the guests and the quaking bride. I remember my heart pounding as I cleared the twenty-yard stretch between bridal car and church door myself another April, almost seventy years later. I can see from my grandparents’ wedding photographs that the crowds were just as thick back then. Perhaps fewer tourists in those days than locals up to see the sights. But I doubt that Beryl was as overawed as I was. The great and the good were there for her wedding. And that’s pretty much what she would have wanted.

As Lilla entered the church through the onlookers outside and saw the pews stacked with grandees, she was bursting with pride. But when she was taken to her seat, she found herself, as she still used to say years later, “stuck behind a pillar.” As soon as she and Sir Frank finished their procession out of the church, he slipped away. And worse was to come. The reception was at Claridge’s—still just about London’s smartest hotel. When Lilla tried to join the traditional receiving line of the bride and groom and their parents, all welcoming the guests, she was pushed away. The Bowaters turned their backs. They were not, even if she was the groom’s mother, going to introduce her to any of their friends. For years afterward, Lilla’s daughter and her husband, Alice and Havilland de Sausmarez, fumed, their daughter tells me, about how badly Lilla was treated that day, at her own son’s wedding. And Lilla herself swore she’d heard the Bowaters mutter “that yellow woman” under their breath.

It must have brought everything that Lilla thought she had overcome flooding back. It wasn’t just the Howells and the Rattrays, now it was the Bowaters, too, who regarded her as a second-class citizen. Lilla was still just a foreigner from China, the offspring of one of the thousands of British families who had gone to better themselves abroad. A colonial whom people like the Bowaters—who had been wealthy enough to remain in Britain—didn’t want to see coming back.

Lilla turned to the trick that had worked before and took off. Ran. Tried to outpace the humiliation by rushing from visit to visit with her relatives and acquaintances around the globe. But almost as soon as she had picked up enough speed to start to forget, she was brought to a shuddering halt.

Throughout the twenties, the Eckfords had been spending money almost as fast as they made it. Edith and Dorothy—as Andrew’s only real children—owned the firm. Vivvy and Reggie ran it for them on fat salaries. Toby could look after Ada. The brothers passed money on to Lilla and their mother, Alice. Alice was still living in the house on Crystal Palace Park Road with two servants, a driver, and a shopping habit of buying a dozen of everything she liked.

But as business was flourishing, it didn’t seem to matter too much what anyone spent. The political situation in China was as stable as it had been at any time in the twentieth century, which was not very. Chiang Kai-shek’s Northern Expedition had been more or less successful— he had managed to keep an army together over thousands of miles and for many months. But almost as soon as his Nationalist troops had taken Tientsin and Peking in late 1928, things began to turn rocky. Various Nationalist factions had split away. Chiang’s somewhat shaky alliance with the Communists had fallen apart. The latter were now regrouping in opposition to him. Meanwhile the warlords whom Chiang had brought under control on his way north kept changing alliances.

Nonetheless, there was still enough of a Nationalist government to begin discussing changes to the treaty-port system and the abolition of the Chinese bugbear of foreigners’ extraterritoriality. But, in 1931, these discussions were suddenly interrupted when Japan, still aggrieved by the decision of the Washington Conference of 1921–22 to remove Shantung from its control, invaded Manchuria.

None of the other foreign powers made a fuss about this move by Japan. And what a mistake that would turn out to be. Perhaps, at the time, they were so grateful that the Nationalist government’s efforts had been diverted away from the treaty ports that they decided, both selfinterestedly and shortsightedly, to avert their eyes. And, of course, the Westerners in the treaty ports were on very friendly terms with the Japanese in China, who were, to some extent, their colleagues. I have a photograph, taken around this time, of Vivvy and a dozen other Chefoo businessmen at the end of what had clearly been a long evening with their Japanese hosts. Half-empty plates, bottles, and cushions are strewn over the floor and low tables. The guests are all men. One of four Japanese women in makeup and kimonos—perhaps they are geisha?— is laughing as she refills Vivvy’s glass to the brim. The Westerners appear slightly the worse for wear. Vivvy perhaps most of all. The Japanese are strikingly self-composed.

A few months after they had invaded Manchuria, the Japanese explained politely to the British and the American press in Shanghai, over caviar and champagne, that they needed to defend Japanese civilians in the city’s Chinese residential district of Chaipei. That very night, Japanese troops mounted machine guns on their motorbikes to spray the streets with bullets. And the Westerners—some dressed in evening clothes—literally stood by and watched. The next day, the Japanese bombed the area. Over the following couple of months, several thousand Chinese civilians were killed.