Lilla's Feast (27 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

Still, Lilla would have found this less worrying than what she had seen in Berlin. For the past twenty years, Japan had been trying to secure a foothold in China. And, so far, it had made little difference to the foreign residents of the treaty ports whether the Nationalists, the warlords, or the Japanese were in control of the surrounding countryside. There was always something or other going on out there, and, as one former treaty porter told me, people were “so used to trouble” that they ignored it—“it never even hit us.”

Perhaps, if your life was in China, if that was where your home, your business, your family and friends were, it was simplest to see things that way.

What Lilla, the Eckfords, Casey, and everyone else who stayed may have underestimated—or perhaps chose to close their eyes to—was quite how deep the veiled Japanese resentment of the Western powers’ presence in China ran. If the Americans had Latin America, the French had North Africa, and the British had India, then the Japanese felt that China should be theirs and theirs alone. And just as Lilla was taking her life back to China, to settle down in the only place that she had ever felt was really home, the Japanese army in Manchuria was poised, waiting for its moment to pounce.

From Harbin, it was just two more days to Chefoo. One day on the Manchurian train to Dairen—a port near Port Arthur on the Liaotung Peninsula that hovers over Chefoo in the Yellow Sea. A final night in a hotel. Then a few hours by boat to Chefoo.

Chefoo in the 1930s was a far busier town than the quiet port that Lilla had left thirty years ago. The full-time foreign population had grown to about one thousand. And, according to Chefoo’s entries for those years in the China Directory—an annual handbook of facts, figures, and firms in the treaty ports—there were now over thirty trading firms, half a dozen missions (including the flourishing mission schools), three banks and a building society, and the

Chefoo Daily News

newspaper. Not to mention a delicatessen, an old-style German restaurant—and a brand-new amusement park. Chinese Customs was still battling with the inevitable smuggling around Chefoo’s rocky coastline, bandits still roamed the countryside, and although an area was still nominally recognized as international, the residents had handed over the running of it to the same Chinese committee that ran the Chinese part of the town. The old city was now a labyrinthine market with entire streets selling just silk, just livestock, or only padded clothes. There were even dedicated markets for thieves and prostitutes—those who managed to side-step the Chinese authorities. The local government was still executing convicted criminals like cattle on Second Beach. They carted them through the town in bamboo cages wearing dunce caps on their heads and, with the aid of the modern gun, managed to kill fifty at a time in ten minutes flat.

The sea was bustling. Sampans idled off the main beach as fishermen dived for octopuses on the seabed. Basking sharks drifted in through the reef, and, at night, the bay glowed with phosphorescence. On the other side of Consulate Hill—many of whose former consulates were now occupied by wealthy trading families—the harbor was crammed throughout the summer months. The U.S. Navy had started using Chefoo as a base from May to September each year. A huge local building boom had started to try to accommodate the sailors’ families that followed the ships. But some of the U.S. Navy men still came alone. At four o’clock every afternoon, the sailors flocked ashore on “liberty boats” to enjoy the cabarets that moved up from Shanghai for the summer. The bars along the waterfront were packed to overflowing, the girls and their madams leaning over the low garden walls beckoning to potential customers.

Chefoo’s slightly more old-fashioned pleasures were still on offer, too. There were mule rides and rickshaw rallies for picnics up at the dragon temple on Temple Hill. There were carriage drives along the avenues between the mulberry orchards that were the local silkworm factories. Lunch at the Chefoo Club started with a gin and tonic at noon. Its visitors could choose from a men’s bar, billiard room, mixed cocktail lounge, mixed tea lounge, a ladies’ lounge, and the terrace overlooking the beach. After the offices closed at four, Chinese players waited on standby at the tennis courts for foreigners who turned up without a partner. Later, there was bowling in the old wooden alley in the club’s basement.

Business, on the other hand, was changing. The global economic depression had almost killed off the old hairnet and straw-braid markets—boaters and bonnets were luxuries that were not being replaced. And as soon as people again had money to spend, they wanted something quite different. The new fashion seemed to be for embroidered bed linens and table napkins. Simple, pretty, feel-good items that helped lift the gray gloom that had descended on people’s homes. And that is just what Lilla’s fiancé, Casey, made.

Casey & Co. was housed in a large building right on the waterfront overlooking First Beach. It was at the harbor end, about a hundred yards from the Chefoo Club, which was tucked into the bottom of Consulate Hill. An L-shaped brick building with flashes of red and white lightening up the predominantly gray stone, it curved in a great colonnade of arched windows along the first and second floors. Inside sat rows of Chinese women. Many of them had to be brought to work in wheelbarrows, as they couldn’t walk. According to Chinese tradition, whether rich or poor, women had their feet tightly and agonizingly bound in early childhood—usually at around the age of five—to stop them from growing any further. Claire Malcolm Lintilhac, who worked as a nurse in Chefoo and examined these grotesquely crippled feet, describes the process in her memoirs:

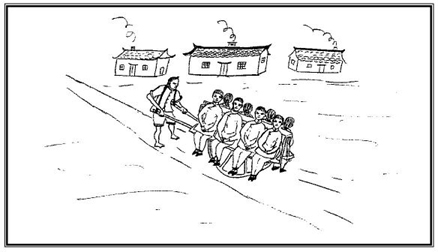

Girls with bound feet on their way to work in a hairnet factory. Drawn by Claire Malcolm Lintilhac.

It had to be done very carefully if serious complications such as gangrene were to be avoided. Slowly but firmly the four small toes were folded under, gradually embedding them into the ball of the foot leaving the big toe free. As the foot grew longer, so the instep was bent under and back, giving the foot its abnormal arched appearance. Bathing, powdering and rebinding had to be done at careful intervals. But as long as the foot was still growing, the intense pain was always there.

Although this barbaric practice had been officially abolished with the end of the last imperial Chinese dynasty—the Ching dynasty—in 1911, it was many years before it stopped, perhaps because it made girls more attractive to their future husbands. It certainly prevented them from running away or even leaving the home alone. Going to work in a factory was one of the few ways in which they could go out at all.

Once there, these women spent all day sewing tiny, neat stitches into lace-fringed tablecloths and handkerchiefs. Delicate flowers seemed to spread across the linen under their fingertips. Miniature pink lilies, their petals falling open as they died to reveal the suggestive folds within. Bright blue cornflowers with orange centers and pure white daisies. White globes with yellow lips and great headdresses of scimitar-shaped petals, strewing leafy twigs and red and black berries in their path. As I run my fingers over the cross-stitches, straight stitches, and little French knots on the linen that Lilla gave my mother and me, I remember Lilla’s enthusiasm still bursting through that stutter, years after Casey & Co. had gone: “They are j-j-just so p-pretty. B-B-Beautiful, aren’t they?” Lilla loved Casey’s embroidery. She was so keen on it that, when she arrived in Chefoo, she didn’t marry Casey straightaway. She made the most of the way in which the world had changed since she had grown up and went to work in his business.

Even fifteen years after the end of the First World War, surprisingly few women were working. The worldwide depression had both cut the number of jobs available—and those that existed tended to go to men—and dampened the adventurous mood of the twenties. According to Mary Taylor’s social history of women in the twentieth century, even the fashions seemed to push them back into more traditional roles: “In keeping with the more subdued times, the 1930’s saw a return to a new femininity. The androgynous look of the 1920’s disappeared as longer hair became fashionable and women claimed back their curves. Clothes were more restrained and skirts lengthened.” And “women, with a few notable exceptions, seem to have disappeared,” either “eclipsed by economic problems” or “hidden behind net curtains.”

But Lilla was not one to hide. Instead, she became one of just three European businesswomen in Chefoo. Another, Miss Weinglass, worked at the ICI (Imperial Chemical Industries) office. And a Mrs. Rouse ran a mail-order company for embroidery and silk. Lilla did much the same thing. She helped choose the patterns and colors for new designs. She layered samples in boxes overflowing with tissue paper and sent them to prospective clients in the new markets of Australia, South Africa, and the Netherlands. She helped look after the women in the factory. And Casey made it clear to everyone that she had the authority to sign for the whole firm.

But, after everything that had happened—bowing and scraping to Arthur’s headmaster, the Rattrays and Malcolm’s will, the world economy collapsing, then Cornabé Eckford, Lilla was no longer going to put all her eggs in one basket and rely on Casey alone. She was determined, absolutely determined—would be until the day she died—to have money to give to her children and increasing number of grandchildren.

So, for the first time in her life, as well as working in Casey & Co., Lilla went into business on her own. Earth was being flattened and foundations laid on every square inch of spare land in Chefoo. Ninety years after the first treaty ports were opened, ever-increasing numbers of foreigners born in China were reaching retirement age. Many of them were choosing to retire to the seaside at Chefoo—perhaps for the scenery, perhaps for the air, or perhaps because they felt safe in the shadow of the great U.S. warships that loomed offshore for half the year. And as the American naval presence swelled, there was a never-ending stream of wives and children looking for homes to rent. Now that she was earning a living at Casey & Co., Lilla decided to take the small amount of capital that Ernie had left her and join in this property boom. Houses, she clearly thought, were a safe investment. Bricks and mortar couldn’t vanish or become worthless overnight as so many stocks and shares had done in the Wall Street crash. And not only when rented out did houses provide an income, but they could also increase in value, giving her something substantial to leave to Arthur and Alice.

It didn’t occurr to her that the treaty ports might simply cease to exist.

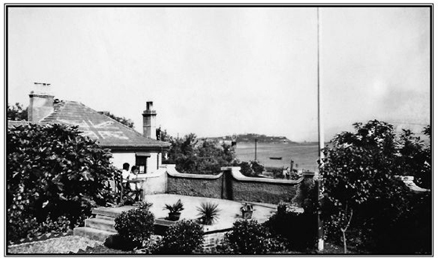

The development that Lilla chose to invest in was called the Woodlands Estate. It was at the far end of First Beach from the club, beyond the boarding schools, on a slope called East Hill that overlooked the bay. She could afford five houses. She bought one that was already there and four plots of land upon which to build. She threw herself into the project with pride. “My little houses,” she called them in her letters back to England, as though they were her children. I still have her photographs of the completed buildings. Their architecture was a curious fusion of East and West. Each house had an eastern single story, but dormer windows poked through the roof. The roofs themselves were tiled and square-chimneyed, yet their ridges fell into an oriental upward curve. The windows had both glass and shutters and were a mixture of traditional English triple bays and ornately corniced tall twin rectangles. Even the garden walls weren’t flat, but curved up into gentle ramparts, hatted with single stone slabs, a miniature version of the walls around the Casey compound.

Lilla clearly thought through what her tenant families might need.

“One of my houses at Chefoo”: Lilla’s property empire

The photographs show that, on the outside, each house had a veranda on which you could sit in the shade and look out over the beach, the lofty rooftops on Consulate Hill, and the string of green islands beyond. In front of the veranda, and to the side, was a little lawn for the children to play on. Beyond this, a flower bed, filled with the plants that would grow best in Chefoo. Coming in and out on short leases, her tenants wouldn’t have a chance to build a garden of their own. And most of them would be too busy with young children.