Lilla's Feast (28 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

Inside, she packed the houses with almost everything practical she could think of. The lists of contents I found at the bottom of an old briefcase in my parents’ attic include flower stands and brass vases, hat stands and newspaper racks, bridge tables, candlesticks, linen baskets, hot-water bottles, wastepaper baskets, jelly molds, champagne glasses, cake plates, card trays for visitors’ cards, ashtrays for smokers. Lilla even hung pictures on the walls.

When the houses were ready, Lilla welcomed the first families in. She helped mothers find amahs to look after the “young ones.” She showed them where to buy the best food. And how to bargain for a good price.

She would still have remembered how much that could matter.

Lilla married Casey on New Year’s Day, 1935. She didn’t think it was right to marry in the church in Chefoo again, especially not another Ernest, a man with the same name. So they went to Shanghai and stood in front of the altar in the grand British cathedral there. Not a young bride and groom in the first flush of love, but a couple with lives already ingrained on their faces. Casey was in his sixties. Lilla was fifty-two. She was beaming from ear to ear—with the contentment of a woman who had finally drawn all the strands of her life together.

None of her family believed her when she said she was in love with Casey. She felt obliged to justify it time and time again. “He gives me everything a woman could want,” she told them. Well, they didn’t doubt that. She even tried the argument that he needed her: “Poor lamb . . . If anything happened to me, I simply don’t know what would happen to him.” That, too, was true. Casey had been the epitome of a lonely bachelor before Lilla had swept back into his life. Admittedly, he had been looked after meticulously by Chinese servants who seemed to know what he wanted before he did himself, but even that was nothing compared to having Lilla around.

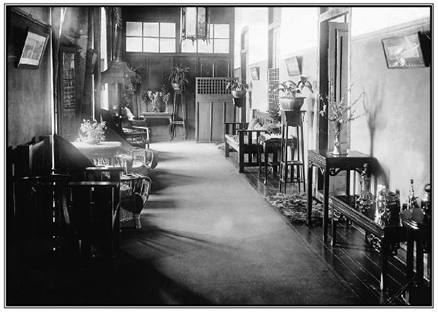

Casey’s home was an apartment along the seaward side of the Casey & Co. building. Lilla moved in and started to wave her magic wand. Instead of the long row of hessian-shaded windows that marked the factory, the arches in front of the living quarters had been opened into a shaded cloister. Behind this, a long hall ran the length of the building. When Lilla found it, it must have felt like a waiting room—a few uncomfortable chairs in a drafty corridor. Without a moment’s hesitation, she transformed it into a miniature version of one of those old-fashioned galleries that run long and wide through old English stately homes and were the center of family life. She lined the walls with side tables crowned with flower arrangements, ornaments, and plants exploding from their pots. She hauled in armchairs and sofas, creating different corners in which to chat, read, or even sew. On the window side, beneath the sunlight that poured in off the sea, the furniture was wicker. On the apartment side, and against the wood paneling at the far end, it was warm, dark wood. She threw carpets and rugs down on the floor, hung paintings at a tilt out from the high walls so that you could enjoy them sitting down, stuck silk-shaded standard lamps in the dark corners and hand-painted Chinese lanterns around the bulbs hanging from the ceiling.

Once Lilla had sorted out Casey’s home, she started to organize his social life. She found the best chef in Chefoo and lured him over to work for her. Together they prepared weekend lunches famous throughout the town. Lilla constructed her lunch parties carefully, Rugs tells me. Never more than eight guests, and, phone call by phone call, she painstakingly built up a crowd that she knew would work well together.

The hall, Casey and Lilla’s apartment, Chefoo

She draped her long dining table with Casey’s beautifully embroidered tablecloths and folded those flower-strewn napkins at each place. Down the center of the table stretched pretty objects, silver dishes, flowers low enough to talk across. Every silver knife, fork, and spoon shone so brightly that Lilla could see her own reflection in them, clear as day.

The meals began with soup. Then something light. Salt-and-pepper prawns in lettuce so crispy that it dissolved on your tongue, leaving the fresh flesh of the prawns—hauled out of the Chefoo sea that morning—to fall away between your teeth. A main course came next. Sometimes a British roast, more often a great sizzling Chinese dish, a jamboree of just-cooked slithers of beef or duck and thin slices of still-crunchy pepper whose skin had just begun to bubble under the heat and melted at the end of each bite. Sauces that were an intriguing combination of sweet and salty. Sauces that coated the food but were still light enough to run off the edge of a spoon.

Then came the sweet courses. First a steaming pile of treacle, stewed fruit layered into biscuit and cream, towering, wobbly jellies and blancmange, or even a baked Alaska, carried triumphantly into the dining room, its meringue crust still cooking but the ice cream inside deliciously cold. As soon as this was swept away, a row of intricately laced sponge and sugar baskets containing sweets and crystallized fruits appeared along the table, each rising curl a noodle-thin strand sculpted into shape and coated with sugar before baking. Finally, with the coffee, came the cake. In any case, it was teatime by now. “If you sat down at one,” says a regular guest, “you’d have been hard pushed to leave by six.” And so, before they’d had a chance to haul themselves up from the lunch table, Lilla would be tempting her guests with lightly buttered scones and jam, pastry-encased fruit tarts, the slices of strawberries, gooseberries, and peaches fanning out from the center of each tiny cake, and alcohol-soaked raisin breads and sponges that pinned you to your chair as their vapor engulfed your eyes and nostrils.

After lunch at Lilla’s, Chefoo, 1938: from left, Mabel, Lilla, Vivvy, Casey, and Rugs

I have a photograph, taken in the courtyard of the Casey & Co. compound after one such lunch. Lilla is smiling. Not a just-for-the-camera sort of smile, but a smile that has taken over her whole face— her eyes, her eyebrows, her cheeks—and her body. Her head is up, her shoulders are relaxed, her arms by her sides, the fingers of her left hand loosely clasped in those of the right. She is standing between Casey and Mabel. Vivvy is behind her. Rugs is at the end of the row. They are all grinning away as though they are still laughing over the last joke, still savoring the last glass of wine or brandy, the last cake. I think this was one of the happiest times of Lilla’s life.

She was making beautiful things to sell. She had her own little business as well. She organized. She entertained. She played her Steinway. She served tantalizingly delicious food out of her own kitchen. She was driven around the town and countryside in a shiny black sedan car that Casey had given her and that was certainly as smart as anything Ada owned. And even if she may not have been madly in love with her husband, even if she didn’t tremble at his every touch, she found his love for her hard to resist.

From the moment they met, Casey had adored her wholly, without reservation. “He doted on her.” Casey’s love was one of the few things in Lilla’s life that she hadn’t had to fight for. He made her feel like the most precious, valued, loved woman in the world. “Such love,” she wrote, “no man has given to a woman.” He needed her. When she was away—with her brother Reggie in Tsingtao, with friends in Shanghai, or when she dashed back to England on the Trans-Siberian Express to see her children and Ada—Casey took care of her little houses himself, cleaning them in between tenants. His attempts were not always successful, but the mere fact that he tried so hard on her behalf meant a lot to Lilla: “The poor lamb did his utmost . . . & felt very proud.” But when the tenants went in, they said it was dirty—“his disappointment!!! So it shows you,” she wrote to her son, as houseproud as ever, “that my presence is necessary—as no tenant that goes into my houses when I am there says it is dirty!!! I look into every corner . . . of course I will tell him, he did very well indeed.” And I think she found looking after him surprisingly fulfilling. On the evenings that they were in alone together, I can almost hear him reading aloud to her in a soft, lilting, unclipped voice and telling her how fabulous she was.

And the love that grew out of this mutual caring, this holding-hands sort of love, would prove to be stronger and more constant than any Lilla had known before. It was a love that would survive all the terrifyingly high hurdles yet to come.

Just as Lilla started to build her new life in Chefoo, the wheels that would ride it into the ground were already beginning to turn. For a couple of years, the area around Chefoo remained peaceful, but in the rest of China, civil war was raging and Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party, still nominally in power, was losing popular support. One of the reasons for this was that, rather than retaliate against the Japanese violence of the early 1930s, Chiang had ignored it and focused on trying to eliminate his rural Communist opposition instead. By the midthirties, support for the Nationalists was at such a low ebb that in December 1936, Chiang was taken prisoner by a local warlord in Sian. A few months later, he was released, but he was weakened by the humiliation—he had been captured wearing only his pajamas—and Japan saw the moment to invade.

In July 1937, Japanese soldiers swarmed south from Manchuria along China’s prosperous eastern coast and took Peking and Tientsin, their bayonets stopping only at the gates of the foreign concessions in the latter. In August and September, they were locked in battles over Shanghai. And, although the Japanese again avoided entering the international settlement, several foreigners—and several thousand Chinese—were killed in their bombing raids on the main shopping streets. December of that year saw one of the worst atrocities in modern warfare with the Japanese “rape” of the city of Nanking, where Chiang Kai-shek’s fragile government was based. The Japanese army ran wild through the city with a mind-numbing, inhuman viciousness. Chinese women were gang-raped by soldiers and bayoneted like pincushions. Others were simply shot and sliced to pieces. Few survived. The lucky ones managed to take their own lives before the soldiers reached them.

Again, the foreigners were carefully sidestepped. Yet, in the treaty ports, a chill began to set into expatriate bones. Until recently, the Westerners argued with themselves, the Japanese had been their colleagues. To an extent, they still were. The Japanese would never, they thought, they convinced themselves, dare do anything like this to Westerners. What they missed, or simply didn’t want to see, was that the important thing to the Japanese was not race; it was the strength of the governments of the people they were targeting. Two decades earlier, the Japanese had waited for the Germans to find themselves at loggerheads with the rest of the treaty-port nations in 1914 before slipping into their place and taking over their Chinese territories. And, as Lilla herself had seen, back in Europe, in those countries to which so many of the treaty-port residents were supposed to belong, trouble was already brewing.

Having digested Peking, Tientsin, and Shanghai, the Japanese army reached Chefoo in the last days of 1937. At first, the Westerners were relieved to see the red-and-white-flagged vehicles rolling in. As news of the Japanese advance had swept through the country, the Nationalist Army had destroyed the infrastructure in Japan’s path and broken up the Japanese-owned factories and warehouses. It then fled toward its new headquarters in Chungking in the west of China, which the Japanese chose to ignore. The treaty ports were left with no semblance of law or order and at the mercy of rioters and looters encouraged by the damage that had already been done. The damage in Chefoo—where there were few industrial units; even Casey & Co. consisted of seamstresses rather than heavy machinery—was minimal. Still, Lilla must have felt very vulnerable. The Casey building was one of the largest in the center of the town. And anarchy is terrifying. The crowd was attacking the Japanese today. Tomorrow it could be the British.

In industrial Tsingtao, just a couple of hours from Chefoo, the looting was so bad that, on New Year’s Eve, Lilla’s brother Reggie organized a force to try to keep control until the Japanese arrived. Not only had a large number of sites been destroyed, but the departing Nationalists had aggravated the situation by releasing a couple of thousand criminals back onto the streets. Ignoring the growing tensions among their governments back home, the British, Americans, White Russians, and Germans clubbed together to form the Tsingtao Special Police. The doctors were German, the drivers and intelligence officers Russian, and the British and Americans wielded the “sticks, pieces of board, anything available” that they could find. They charged the crowds of rioters that they found attacking waterworks, Chinese villages, and foreign property. The Tsingtao Special Police held the town for ten days. On January 10, Japanese marines began to land. In a formal ceremony, Reggie handed over Tsingtao to Japanese Rear Admiral Shisido. In return, Shisido handed Reggie a delicately engraved and painted china urn. “It was absolutely beautiful,” says Rugs—who had been fighting with the Tsingtao Special Police, too—as though the very beauty of it, the extent of the Japanese gratitude, should have alerted them as to what was to come.