Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

Lion of Liberty (2 page)

To this day, many Americans misunderstand what Patrick Henry's cry for “liberty or death” meant to him and to his tens of thousands of devoted followers in Virginia's Piedmont hillsâthen and now. A prototype of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American frontiersman, Henry

claimed that free men had a “natural right” to live free of “the tyranny of rulers”âAmerican, as well as British. A student of the French political philosopher Montesquieu, Henry believed that individual rights were more secure in small republics, where governors live among the governed, than in large republics where “the public good is sacrificed to a thousand views.” Rather than the big government created by the Constitution, Henry sought to create an alliance of independent, sovereign states in Americaâsimilar to Switzerland, whose confederation, he said, had “stood upwards of four hundred years . . . braved all the power of . . . ambitious monarchs . . . [and] retained their independence, republican simplicity, and valor.”

2

claimed that free men had a “natural right” to live free of “the tyranny of rulers”âAmerican, as well as British. A student of the French political philosopher Montesquieu, Henry believed that individual rights were more secure in small republics, where governors live among the governed, than in large republics where “the public good is sacrificed to a thousand views.” Rather than the big government created by the Constitution, Henry sought to create an alliance of independent, sovereign states in Americaâsimilar to Switzerland, whose confederation, he said, had “stood upwards of four hundred years . . . braved all the power of . . . ambitious monarchs . . . [and] retained their independence, republican simplicity, and valor.”

2

The son of a superbly educated Scotsman from Aberdeen, Henry grew up in Virginia's frontier hill countryâfree to hunt, fish, swim, and roam the fields and forests at will. Far from government constraints and urban crowding, everyday life in the Piedmont was an adventure with wild animals, Indian marauders, and fierce frontiersmen. Unable at timesâor unwillingâto distinguish between license and liberty, they viewed government with suspicion and hostilityâand tax collectors as fit for nothing better than a bath in hot tar and a coat of chicken feathers. The results were often conflict, gunfire, bloodshed, death, and quasi-civil war. For backcountry farmers and frontiersmen, the business end of a musket was the best way to preserve individual liberty from government intrusion. And Patrick Henry was one of themâtheir man, their hero. George Washington viewed frontier life as anarchy; Henry called it liberty!

Neither saint nor villain, Henry was one of the towering figures of the nation's formative years and perhaps the greatest orator in American history. Lord Byron, who could only read what Henry had said, called him “the forest-born Demosthenes,” and John Adams, who did hear him, hailed him as America's “Demosthenes of the age.”

3

George Washington “respected and esteemed” him enough to ask him to serve as secretary of state, then Chief Justice of the United States. Virginia Patriot George Mason called Henry “the first man upon this continent in abilities as well as public virtues” and the Founding Father most responsible for “the preservation of our rights and liberties.”

4

3

George Washington “respected and esteemed” him enough to ask him to serve as secretary of state, then Chief Justice of the United States. Virginia Patriot George Mason called Henry “the first man upon this continent in abilities as well as public virtues” and the Founding Father most responsible for “the preservation of our rights and liberties.”

4

Unlike Washington and Jefferson, who tied their fortunes to Virginia's landed aristocracy, Henry achieved greatness and wealth on his own, among ordinary, hard-working farmers in Virginia's wild Piedmont hills west of Richmond, where independence, self-reliance, and a quick, sharp tongue were as essential to survival as a musket.

A charming storyteller who regaled family and friends with bawdy songs and lively reels on his fiddle, Henry was as quick with a rifle as he was with his tongueâand he fathered so many children (eighteen) and grandchildren (seventy-seven at last count) that friends insisted he, not Washington, was the real father of his country. His direct descendants may well number more than 100,000 todayâenough to populate the entire city of Gary, Indiana.

Remembered only for his cry for “liberty or death,” Henry was one of the most important and most colorful of our Founding Fathersâa driving force behind three of the most important events in American history: the War of Independence, the enactment of the Bill of Rights, and, tragically, the Civil War.

Chapter 1

Tongue-tied . . .

Eloquence had flowed from his family's lips for generations. The echoes of his kinsmen's voices resounded from the pulpits in Midlothian and Edinburgh to the halls of London's Houses of Parliament. Even in the far-off hills of central Virginia, the dazzling voice of his uncle and namesake, the Reverend Patrick Henry, drew worshipers from miles around for the rapture of his wondrous words each Sundayâwords, it seemed, from God himself.

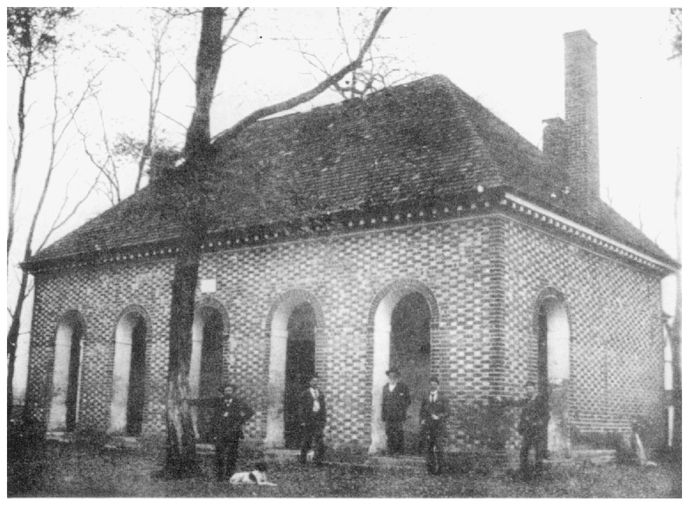

It was quite natural, then, that spectators flocked to Hanover County Courthouse on December 1, 1763, for the inaugural courtroom appearance of the Reverend Henry's nephew, Patrick Henry Jr., as defense lawyer in a major case. Although he had spent three years practicing mostly “paper law” (deeds, wills, and such) and defending petty thieves, this was his first appearance in the theatrical setting of a major courtroom case. Headlined in the press as the “Parsons' Cause,” the case had far-reaching religious and political implications for both Virginia and Mother England, where the official Church of England supported itself by taxing landowners in each parish, regardless of whether they were Anglicans or not. In the Parsons' Cause, a Church of England priest sued the vestrymen and landowners of his parishâalmost all of them small farmersâfor failure to pay all their taxes in 1758. If Henry lost the case, many would lose their homes and lands.

The Hanover County Courthouse, where Patrick Henry began practicing law and won fame in the Parsons' Cause case.

(FROM A NINETEENTH-CENTURY PHOTOGRAPH)

(FROM A NINETEENTH-CENTURY PHOTOGRAPH)

Henry had started well enough, shooting to his feet to object when appropriate, and successfully countering his opponents' objections during jury selection, and he'd done well enough during the main trial. But now it was time for his closing argument, and, as an eerie stillness settled over the courtroom, he moved to center stage, bowed his head, and stared at the floor. Seconds went by . . . a minute . . . then another. . . . He seemed at a loss for words. Inquietude spread across the room; spectators exchanged puzzled looks with one another, shifting in their seats uncomfortably. The plaintiff's attorney broke into a snide grin; defendants groaned, and Patrick Henry's fatherâthe presiding judgeâslumped in his chair in embarrassmentâhis expectations for his son all but crushed.

Judge John Henry finally shook his head in despair and prepared to pound his gavel and end his son's travail with a summary judgment for the plaintiff. It was a difficult moment. . . .

Neither he nor the rest of Henry's family could understand why twenty-seven-year-old Patrick was flirting with failure againâas he had in three previous careersâtwice as a storekeeper and once as a farmer. He was intelligent, hard-working, cheerful, personable, learned, extremely talented in innumerable ways and, above all, he came from solid, well-educated, hard-working, and successful Scottish and Welsh stock.

The judge, his father, had been born in Aberdeen, Scotland, to a devoutly Anglican family “more respected for their good sense and superior education than for their riches.”

1

At fifteen, John Henry had won a Latin composition prize and a scholarship to Aberdeen University, where he spent four years before emigrating to the United States at the behest of John Syme, a boyhood friend and Aberdeen schoolmate. Young Syme had sailed to America three years earlier and grew rich growing tobacco and speculating in land. His education, erudition, and wealth propelled him into Virginia's highest social and political circlesâand such sinecures as a militia colonelcy and membership in the House of Burgesses, the colonial legislature. At Syme's urging, John Henry followed his friend to America in 1727, learned surveying and, in partnership with Syme, began speculating in land. Surveying skills were essential in Virginia, where tobacco crops consumed soil nutrients after four to six years and forced planters to find virgin lands in which to plant new crops. Speculators joined the search, of course, and those who were first to claim virgin lands reaped the most profits reselling claims to planters.

1

At fifteen, John Henry had won a Latin composition prize and a scholarship to Aberdeen University, where he spent four years before emigrating to the United States at the behest of John Syme, a boyhood friend and Aberdeen schoolmate. Young Syme had sailed to America three years earlier and grew rich growing tobacco and speculating in land. His education, erudition, and wealth propelled him into Virginia's highest social and political circlesâand such sinecures as a militia colonelcy and membership in the House of Burgesses, the colonial legislature. At Syme's urging, John Henry followed his friend to America in 1727, learned surveying and, in partnership with Syme, began speculating in land. Surveying skills were essential in Virginia, where tobacco crops consumed soil nutrients after four to six years and forced planters to find virgin lands in which to plant new crops. Speculators joined the search, of course, and those who were first to claim virgin lands reaped the most profits reselling claims to planters.

Within four years, John Henry had accumulated more than 15,000 acres in three counties, including a 1,200-acre plantation in Hanover County, about sixty miles upriver from Virginia's capital at Williamsburg. In 1731, John Syme died, and after letting two years elapse in the interest of decency, Henry married Syme's “most attractive” widow, Sarah. Of Welsh descent, she was a devout Presbyterian, and brought a dowry of 6,000 acres to the marriage, along with a step-son, John Syme, Jr. Although John Henry scorned her religion, he tolerated his wife's heresy in silence, given all the other benefits she brought to their marriage.

“A person of a lively and cheerful conversation,” with “remarkable intellectual gifts” and “an unusual command of language,” Sarah traced her

lineage to two of Virginia's oldest, most accomplished familiesâthe Winstons and Dabneysâwho welcomed John Henry into Hanover County's ruling circle by arranging his appointments as a vestryman of the Church of England, chief justice of the county court, and colonel of the militia. As a vestryman

and

chief justice

,

John Henry became one of Hanover County's most powerful figuresâonly nine years after his arrival in America. To reinforce his authority he maneuvered relatives into six of the twelve county judgeships and his older brother, Reverend Patrick Henry, into the pulpit of St. Paul's Anglican church. With his brother governing its spiritual life and John Henry its political life, Hanover County evolved into nothing less than a Henry family fiefdom.

lineage to two of Virginia's oldest, most accomplished familiesâthe Winstons and Dabneysâwho welcomed John Henry into Hanover County's ruling circle by arranging his appointments as a vestryman of the Church of England, chief justice of the county court, and colonel of the militia. As a vestryman

and

chief justice

,

John Henry became one of Hanover County's most powerful figuresâonly nine years after his arrival in America. To reinforce his authority he maneuvered relatives into six of the twelve county judgeships and his older brother, Reverend Patrick Henry, into the pulpit of St. Paul's Anglican church. With his brother governing its spiritual life and John Henry its political life, Hanover County evolved into nothing less than a Henry family fiefdom.

British Colonies in 1763.

John and Sarah Henry had nine childrenâtwo sons and seven daughtersâof whom the oldest was William, born in 1735 and named for Sarah Henry's father William Winston. Patrick Henryânamed for his priestly uncleâfollowed a year later, on May 29, 1736. In 1750, with a third child on the way, the Henry family moved from what had been the Syme home into a larger house twenty-two miles from Richmond on an elevationâ“Mount Brilliant”âby the South Anna River, where Patrick Henry, the future lawyer, would spend his formative years.

Â

Prominence, power, and wealth in the Hanover County hills, however, did not mimic Virginia's eastern Tidewater region, where such legendary names as Lee, Fairfax, and Carter reigned over 20,000-, 30,000-, and 40,000-acre plantations from palatial mansions that mirrored their ancestral seats in Georgian England. As hundreds of slaves worked the fields, Virginia's Tidewater aristocracy rode to the hounds and sipped tea by marble-mantled fireplaces that filled each room with aromatic warmth. In contrast, Patrick Henry's childhood home was pure “country”âa two-story, forty-by-thirty-foot rectangular box covered with whitewashed clapboards and topped by a half-story dormered attic. Like most Virginia farmhouses, front and rear doors opened on opposite sides of a large central hall on the ground floor to let breezes flow through and cool the house in summer. Although they spent idle moments on the porch, the hall was the center of family lifeâa combined living room, dining room,

and kitchen. A slow wood fire kept meats crackling on a spit in the open hearth, while stews bubbled in kettles dangling from wrought-iron cranes. Two bedrooms lay off the central room, and a staircase to the second floor led to sleeping areas for children.

and kitchen. A slow wood fire kept meats crackling on a spit in the open hearth, while stews bubbled in kettles dangling from wrought-iron cranes. Two bedrooms lay off the central room, and a staircase to the second floor led to sleeping areas for children.

Other books

Neighborhood Watch by Cammie McGovern

No Good Deed by Allison Brennan

The Reunion by Kraft, Adriana

Z Day is Here by Rob Fox

The Righteous and The Wicked by April Emerson

Return of the Prodigal Son by Langan, Ruth

Cherry Bomb by Leigh Wilder

El vizconde demediado by Italo Calvino

The Man Who Planted Trees by Jean Giono

A Part of Me by Taryn Plendl