Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

Lion of Liberty (8 page)

A few days later, a second mob gathered around a bonfire, drank themselves into a frenzy, and marched to the home of a marshal of the vice-admiralty court to burn it down. Wiser than most targeted victims, he saved his homeâand lifeâby guiding mob leaders to a tavern and buying them a barrel of punch. Another mob, however, was on its way to the home of Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson, a prominent Boston merchant who was a direct descendant of Anne Hutchinson, the early-seventeenth-century religious leader. One of the architectural jewels of North America, Hutchinson's Inigo Jones-style residence bore Ionic pilasters on its façade and a delicate cupola atop its roof. The mob broke down its massive doors and, room by room, set fires in each, and destroyed everything, including Hutchinson's legendary collection of manuscriptsâmany of them significant public papers documenting the history of Massachusetts. It took the mob three hours to dislodge the cupola from the roof and tumble it onto the huge fire below.

The violence in Boston set off an epidemic of violence across the colonies, spreading first to Newport, then to New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston. A mob in Newport, Rhode Island, built a gallows for the designated stamp collector, who fled to a British warship in the harbor and promised to resign. As rioting spread, stamp officers resigned in New Hampshire, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia, and even offshore in the Bahamas. In New York City, a mob of about 2,000 protestors marched through the city, broke open the governor's coach house, and seized his ornate gilded coach and three other vehicles. After seating effigies of the governor and royal officials, they paraded the carriages through town, hung the effigies on a makeshift galley, and burned all the vehicles.

Delegates from eight colonies responded to the Massachusetts call for an intercolonial congress in New York. New Hampshire, North Carolina, Georgia, and, most noticeably, Virginiaâthe most important colonyâfailed to respond or send delegates. In the case of Virginia, the governor had dismissed the House of Burgesses before word of the congress arrived. Speaker Robinson eventually received the invitation, but was far too loyal to the crown to do anything but discard it.

Although physically absent from the Stamp Act Congress, Henry was nonetheless there, as delegates continually cited his seven resolutions. After eleven days of deliberations, the congress approved a “Declaration of Rights and Grievances of the Colonists in America,” with fourteen resolutions that condemned the Stamp Act for depriving colonists of the right of taxation by consent, which it called “essential to freedom.” With moderates outnumbering radicals, however, the Congress stopped short of embracing Henry's positions and asserted, instead, that colonists “glory in being the subjects of the best of kings. . . . That we esteem our connection with . . . Great Britain as one of the great blessings. ...” It concluded with an obsequious assertion that “subordination to the parliament is universally acknowledged.”

26

Even the whimper that ended the declaration could not coax a single delegate to risk treason by penning his name on the document. The only signature that appeared was that of the paid clerk.

26

Even the whimper that ended the declaration could not coax a single delegate to risk treason by penning his name on the document. The only signature that appeared was that of the paid clerk.

Boston's Otis was furious as he stomped out of the meeting to begin the ride home. Once there, he strode into the colonial assembly in

Boston and shouted a challenge to Lord Grenvilleâby then prime ministerâto duel on the floor of the House of Commons in London, to determine whether the colonies were to be free or enslaved by British tyranny. Royal Governor Hutchinson responded by calling Otis “more fit for a madhouse than the House of Representatives.”

27

Boston and shouted a challenge to Lord Grenvilleâby then prime ministerâto duel on the floor of the House of Commons in London, to determine whether the colonies were to be free or enslaved by British tyranny. Royal Governor Hutchinson responded by calling Otis “more fit for a madhouse than the House of Representatives.”

27

After the Stamp Act Congress, Henry's words permeated the debates in every legislature, slipping off every tongue as easily as scriptural passages and provoking adoption of similar resolutions in eight colonies. British authorities recognized they would now need an army to enforce the Stamp Act. “Mr. Henry,” Jefferson declared, “gave the first impulse to the ball of the revolution.”

28

Without knowing it, Patrick Henry's outrage at government taxation had provoked a war for independence that would free his countrymen from British rule.

28

Without knowing it, Patrick Henry's outrage at government taxation had provoked a war for independence that would free his countrymen from British rule.

Chapter 4

We Are Slaves!

As the effective date approached for the Stamp Act to go into effect, Patrick Henry's new friend and political ally, planter Richard Henry Lee, of Westmoreland County, put his name and fortune at risk by calling on Virginians to boycott all things British until Parliament repealed the Act. In what was essentially an act of treason, more than one hundred Virginia planters signed Lee's Westmoreland Protests and inspired similarly prominent men in other colonies to follow suit. Some 200 merchants in New York City, 250 in Boston, and 400 in Philadelphia pledged to stop importing all but a select list of goods from England until Parliament repealed the Stamp Act. Boston's leading merchant banker John Hancock warned his London agent that “the people of this country will never suffer themselves to be made slaves of by a submission to the damned act.”

1

1

By the time the Stamp Act became law, every stamp officer in the colonies had resigned, and, with no distributors to sell stamps, the act could not take effect. Americans nonetheless greeted November 1 as a day of mourning, with church bells tolling throughout the day, from St. John's in Richmond, Virginia, to Boston's North Church. The Sons of Liberty gathered about Liberty Trees in towns and cities across the colonies to hang effigies of Grenville, their royal governors, and any other government official they could think of to blame for their economic woes.

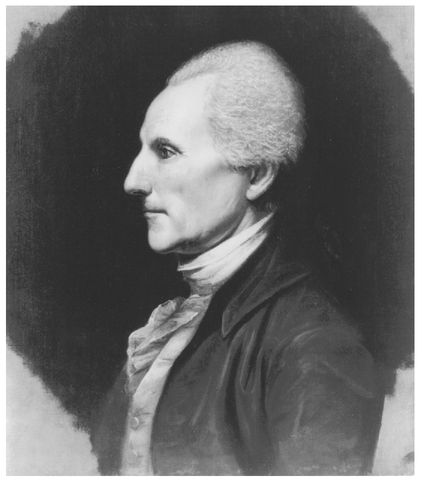

Richard Henry Lee, the Virginia planter whose resolution in the Continental Congressâthat Britain's colonies “are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States”âprovoked the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

The boycott against English imports had terrible economic consequences for English merchants. Colonial merchants owed them about £4 million, and the flow of orders from America had all but dried up. British exports dropped 14 percent, and goods piled up inside and outside British warehouses. Merchants in London, Bristol, Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Glasgow, and every other trading town in Great Britain inundated Parliament with petitions demanding repeal of the Stamp Act.

George Washington observed that,

whatsoever contributes to lessen our importations must be hurtful to their manufacturers. And the eyes of our people . . . will perceive that many luxuries which we lavish our substance to Great Britain for, can

well be dispensed with whilst the necessities of life are (mostly) to be had within ourselves. . . . As to the Stamp Act . . . I fancy the merchants of Great Britain will not be among the last to wish for a repeal of it.

2

well be dispensed with whilst the necessities of life are (mostly) to be had within ourselves. . . . As to the Stamp Act . . . I fancy the merchants of Great Britain will not be among the last to wish for a repeal of it.

2

Washington proved a good prophet. By mid-January 1766, English merchants warned Parliament that they faced bankruptcy unless normal trade with North America resumed immediately. Letters from their trading partners in America promised nothing but armed rebellion if Britain sent troops to enforce the Stamp Act. If Parliament wanted to tax the colonies, they counseled, it should continue the tradition of using indirect, hidden taxes such as import duties. By the end of February, pressure for repeal grew overwhelming and, only four and a half months after the Stamp Act had taken effect, Parliament yielded, without a single stamp having been affixed to a colonial document. In addition, it lowered duties on imported molasses from the French West Indies that New Englanders used to make rum, and it eliminated duties on sugar from the British West Indies, thus reducing mainland prices for two key commodities.

Repeal of the Stamp Act was a humiliating defeat for Grenville and his party in Parliamentâparticularly because it came at the hands of a constituency without a single vote in either the House of Commons or the House of Lords. In the end, the British government had collected no new taxes and left its own treasury and many British merchants far poorer than they would have been had it never passed the act. A far more ominous consequence of the act, however, was the appearance of the first organized opposition to royal rule in the coloniesâprovoked by Patrick Henry and joined by others chafing under the London government's arbitrary regulations and restrictions.

In mid-May, about a month after the actual vote in Parliament, news of America's success arrived in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and other ports. Across the colonies, Americans set aside a day they named “Repeal Day,” to celebrate their triumph over the government of the world's most powerful nation. Merchants broke open barrels of rum, wine, beer, and other beverages for employees, clients, and passersby to toast his Majesty's health, believing false rumors that the young King George III himself had intervened on behalf of the Americans. In Virginia, jubilant city fathers

illuminated Norfolk and Williamsburg and sponsored balls that lasted until dawn. The royal governor would not recall the House of Burgesses until November 1766, but when it reconvened it voted to erect a statue of King George III and an obelisk in recognition of Henry and other patriots who had fought for repeal. (Neither was ever built.) Even Londoners rejoiced over repeal of the Stamp Act. The city illuminated its streets, and its merchantsâecstatic over prospects of renewed trade with Americaârolled out kegs of wine to serve to dancing celebrants in the lanes outside their doors.

illuminated Norfolk and Williamsburg and sponsored balls that lasted until dawn. The royal governor would not recall the House of Burgesses until November 1766, but when it reconvened it voted to erect a statue of King George III and an obelisk in recognition of Henry and other patriots who had fought for repeal. (Neither was ever built.) Even Londoners rejoiced over repeal of the Stamp Act. The city illuminated its streets, and its merchantsâecstatic over prospects of renewed trade with Americaârolled out kegs of wine to serve to dancing celebrants in the lanes outside their doors.

As Americans and Englishmen feted the prospects of economic recovery, bitterness gripped the hearts of the humiliated parliamentary tyrants who had provoked the crisis. Refusing to accept defeat or seek reconciliation, they lit the fuse for the next colonial explosion by quietly passing a Declaratory Act on the very day they repealed the Stamp Act. The act asserted that “the Parliament of Great Britain had, hath and of right ought to have, full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and people of America Subjects of the Crown of Great Britain in all cases whatever.”

3

3

When the House of Burgesses reconvened at the end of 1766, Patrick Henry and his young rebels held a clear majority of votes. Speaker Robinson had died and many of his closest allies had either followed him to the grave or retired in disgust at Henry and other blasphemers intent on undermining the standards of British decency and respect expected from loyal subjects of the crown.

With their Stamp Act victory, Henry and the Sons of Liberty in other colonies stowed their torches and banners, took the helms of their little ships of state and set sail over the uncertain seas to utopia. When Henry reentered the House of Burgesses, he walked with authority. Elected a vestryman in his home county, he was a leader of the established church as well as political leader of the western part of the largest American colony. Indeed, his own familyâhis half-brother, John Syme Jr., his friend and future brother-in-law, Samuel Meredith, and relatives from five western countiesâmade up a powerful backcountry voting bloc that Henry used effectively to influence House of Burgesses legislation. Like other burgesses,

Henry took the traditional oath of office at the beginning of each new session and swore allegiance to King George III, but he followed his oath with proposals for social, economic, and political reforms to dilute royal powers. He also called for separation of church and state, an end to slave importation, expansion of Virginia's domestic manufacturing to ease dependence on British imports, and new rules to prevent political corruption. Named to several key committees, he proposedâand the burgesses approvedâprohibiting the Speaker of the House from serving simultaneously as colonial treasurerâas Speaker Robinson had done. “Away with the schemes of paper money and loan offices, calculated to feed extravagance and revive expiring luxury,” Henry barked at the House.

Henry took the traditional oath of office at the beginning of each new session and swore allegiance to King George III, but he followed his oath with proposals for social, economic, and political reforms to dilute royal powers. He also called for separation of church and state, an end to slave importation, expansion of Virginia's domestic manufacturing to ease dependence on British imports, and new rules to prevent political corruption. Named to several key committees, he proposedâand the burgesses approvedâprohibiting the Speaker of the House from serving simultaneously as colonial treasurerâas Speaker Robinson had done. “Away with the schemes of paper money and loan offices, calculated to feed extravagance and revive expiring luxury,” Henry barked at the House.

Other books

Havoc (Storm MC #8) by Nina Levine

The Krytos Trap by Stackpole, Michael A.

Night Veil by Galenorn, Yasmine

The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov by Vladimir Nabokov

A Place Called Freedom by Ken Follett

Loving The Biker (MC Biker Romance) by Cassie Alexandra, K.L. Middleton

Give Me You by Caisey Quinn

Angel Tormented (The Louisiangel Series Book 3) by C. L. Coffey

To Catch a Creeper by Ellie Campbell