Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (33 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

Me 262 Aces

The next problem addressed was the attack. Sheer speed was wonderful for evading (or surprising) escort fighters, but it could be embarrassing when attacking the much slower bombers. To quote Steinhoff,

Swinging into the target’s wake from above was out because of the danger of exceeding the maximum safe speed, the aircraft having no dive brakes with which to check the acceleration involved in such a manoeuvre. Frontal attack on a collision course with the bombers—a favourite with the

Experten

because the target was then virtually defenceless and the crews of the Flying Fortresses were exposed to the hail of bullets—was also out because the combined approach speeds (about 700mph) made a considered attack impossible.

Even from astern the closing speed was still too high. The truth was that there was no ideal solution to the problem while the aircraft was restricted to attacking with guns. A compromise solution was to take position about three miles astern of the bombers and about a mile higher, then launch into a high-speed, shallow dive, aiming at a point about a mile astern and about 500 metres below. On reaching this the jets pulled up to bleed off speed, after which they were well placed to attack with a more reasonable rate of overtake. But they still had to run the gauntlet of the bombers’ defensive fire, and losses to this cause were still high.

Politics then intervened, and Steinhoff leftJG 7 under a cloud. Shortly afterwards he became a founder member of

JV 44.

In April he encountered USAAF Lightnings. Automatically he dived to the attack:

… the Lightnings loomed up terrifying fast in front of me, and it was only for the space of seconds that I was able to get into firing position behind one of the machines on the outside of the formation. And as if they had received prior warning they swung round smartly as soon as I opened fire.

Pop, pop, pop

went my cannon in furious succession. I tried to follow a Lightning’s tight turn but the gravity pressed me down on my parachute with such force that I had trouble keeping my head in position to line the sight up with him … Then a shudder went through my aircraft as my leading-edge flaps sprang out: I had exceeded the permissible gravity load.

The highly wing-loaded Me 262 was no dogfighter. The Lightnings spiralled away downwards and Steinhoff was unable to follow. His jet had no speed brakes, and it was impossible to dive the Me 262 steeply without reaching its limiting Mach number. A few days later Macky

Steinhoff crashed on take-off and was badly burned. He survived the war to command the new

Luftwaffe.

KURT WELTER

A flying instructor during the first years of the war, Welter joined the

Wilde

Sau

unit

10/JG 300

in the summer of 1943, flying the FW 190A-8. In only 40 sorties he scored 33 victories, four of them by day. In the summer of 1944 his unit was absorbed

by 2/NJG 11.

In December 1944 he started to fly the Me 262 at night, leading a small detachment called

Kommando ‘Weiter’.

Against heavy bombers at night, the great speed of the Me 262 was even more of an embarrassment than it was by day, but it was an excellent Mosquito hunter—the only night fighter handily to out-perform the British aircraft. Welter also evaluated a night fighter variant of the Arado 234, but rejected this on the grounds that the panelled glazing of the cockpit caused too many distracting reflections.

While some of his jet victories were with a standard Me 262, flying under close ground control and using the searchlight illumination system, he also flew a single-seater fitted with the FuG 218 radar. He was credited with two heavy bombers and three Mosquitos with this aircraft. A handful of radar-equipped two-seaters were introduced into service in February 1945, and flown by

10/NJG 11

under Welter’s command, the only jet night fighter unit in the

Luftwaffe.

In all, this unit, between its formation in January and the end of the war, was credited with destroying 43 Mosquitos at night and another five high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft by day. This was achieved in only 70 sorties.

Welter’s exact score is unknown, but is generally agreed to exceed 50 victories, although some sources put it higher. About 35 of these were stated to be Mosquitos, one of which he rammed, although whether this was deliberate or accidental is unclear. He survived the war but is believed to have died in an accident in 1947.

Whatever one’s feelings about the regime for which they fought, the courage and ability of the

Jagdflieger

were beyond question, while their achievements in air combat surpassed those of any other nation by a wide margin. At first their scores were greeted with incredulity in the West, but extensive post-war research has led to widespread acceptance.

The ace fighter pilot is a modern phenomenon, a throwback to the days of the single-combat champion. He was born of the slaughter of the First World War, where tens of thousands of faceless ones died in the mud, slain by men like themselves, but by men whom they rarely if ever saw. At a time like this, heroes were desperately needed.

Air combat effectively commenced in 1915. The early flyers fought in the clean blue sky high above the trenches, man to man. Their achievements could not only be seen but measured, by the number of enemy aeroplanes shot down. Inevitably they became the knights of the air, an illusion fostered by the adoption of their own unique forms of often irreverent heraldry.

Although the average artilleryman was responsible for the lives of far more enemy than the average fighter pilot, it was the latter who attracted the most attention. The fighter aces returned lost qualities to warfare—chivalry and glamour. In fact there was precious little chivalry in air combat, but the aura of glamour, and with it the inspiration to others, remained. The

Jagdwaffe

simply continued the tradition.

In any analysis of the

Experten,

three questions must be addressed. The first is the perennial vexed question of overclaiming, which has bedevilled researchers for many years. The second is, why did the

Experten

outscore their opponents by such a wide margin? The third is, who was the greatest German fighter pilot of all?

Jagdflieger

claims were often inflated to double or treble the true enemy losses. This trend was not of course confined to Germany; it was exhibited by all other nations without exception. There were several ways in which it could happen. The first and most obvious was that more than one fighter attacked the same target in quick succession and all claimed it in good faith. The second was that, while the target was hit and appeared to go down out of control, its pilot recovered at a lower altitude. The third, which applied more to inexperienced pilots, was that they opened fire, felt sure that they scored hits, then took their eyes off the target to clear their tails. Then, when they looked back, they saw an aircraft going down, and optimistically assumed it was their doing. In this connection, playing dead was a widely used ploy to shake off an attacker; if done convincingly this normally led to a mistaken claim.

The

Luftwaffe

checked claims as carefully as circumstances would permit, and a significant proportion were disallowed for various reasons. In some cases, if an enemy aircraft went down into the sea and there were no witnesses, pilots might not even bother to make a claim. The conclusion must be that claims were generally made and upheld in good faith.

The real problem is, what constitutes a victory? An enemy aircraft destroyed qualifies perfectly, but proving that this is the case is another matter. A badly damaged aircraft that had to force-land away from base could easily be repairable. At the other extreme, an enemy aircraft claimed only as damaged might crash unseen, or be struck off charge on its return to base.

If a nonsense on the subject of scores is to be avoided, we must eschew the controversial and emotive word ‘kill’ and work on the principle that an aerial victory occurs when an enemy is defeated in combat in circumstances where the victor believes that it will be a total loss.

A point that puzzles many is, how were the leading

Experten

able to outscore their opponents by such a wide margin? Many factors were involved in this. A superior tactical system in the first years of the war,

which frequently put formation leaders in a prime shooting position, was undoubtedly one. Operational circumstance was another. For example, during the Battle of Britain, not only did the

Jagdflieger

usually have altitude and positional advantages, but their opponents were more concerned to get amongst the bombers than to tackle the fighters.

A principle whereby the highest scorer led the formation regardless of rank aided many to add to their totals quickly, and whereas Allied pilots were rested at frequent intervals, the German practice was to keep them in action for as long as possible. This had the advantage of building up unparalleled experience levels, although there can be no doubt that in the final twelve months of the war many high scorers were ‘flown out’.

The main factor was opportunity. By and large the

Experten

flew more sorties than their Allied opponents, and encountered the enemy in the air far more times. In

Full Circle,

British top scorer Johnnie Johnson compared his record to that of Tips’ Priller:

… with 38 victories, which may be compared with Priller’s 101, for we both fought over the same territory for about the same time, but he saw many more hostile aeroplanes than I did …

At the other extreme, Hartmann entered combat on no fewer than 825 occasions, so, given that he survived and shot straight, his enormous score is hardly surprising. By comparison with some, his sortie-to-victory ratio was relatively modest. Some Allied pilots did much better: to quote but one example, American ace Bob Johnson took only 91 sorties to accumulate his 28 victories. And he flew the supposedly inferior Thunderbolt!

Who was the greatest ace of all? There are many contenders. Galland as a great fighter leader, Hartmann as the absolute top scorer and Marseille as top-scorer against the Western allies—all have their backers. Much depends on what values are assigned to each theatre. The record suggests that victories in the West were much harder to come by than those in the East, with North Africa, with its accent on purely tactical operations, somewhere in the middle. Fighter combat called for great flying skills and marksmanship; tackling the American ‘heavies’ needed

nerves of steel, with a fair helping of luck to aid survival. And what of the night defence of the Reich, facing not only the guns of the bombers and the technically superior Mosquito intruders, but the weather as a third, unrelenting foe?

Regardless of the relative difficulties of each front, the record shows quite clearly that

Experten

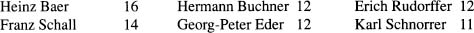

who were successful on one front frequently failed when switched to another. Only two top scorers did really well wherever they were sent. They were Heinz Baer and Erich Rudorffer.

HEINZ BAER

Heinz ‘Pritzl’ Baer began the war as a humble

Unteroffizier

(Corporal) with

JG

57 and ended it an

Oberstleutnant

(Lieutenant-Colonel) with

JV 44.

He opened his account, downing a French Curtiss Hawk 75, on 25 September 1939, and added three more victories by the end of the French campaign. The Battle of Britain almost proved his undoing. Always aggressive, he learned the hard way not to enter a turning fight with Spitfires or Hurricanes. On several occasions he force-landed his badly damaged Bf 109E back in France. Then, on 2 September, once again returning damaged, he was shot down into the Channel by a marauding Spitfire.

Legend has it that Hermann Goering himself watched this rather uninspiring performance. He had the still dripping pilot hauled in front of him and asked him what he thought about while in the water. Baer reportedly replied, ‘Your speech,

Herr Reichsmarschall,

that England is no longer an island!’ This notwithstanding, at the end of 1940 Baer was the top-scoring NCO pilot. Four more victories followed on the Channel front, bringing his total to 17 before

JG 51

was transferred east for ‘Barbarossa’.

Baer shot down 96 Russians over the next year, despite a spell in hospital with spinal injuries. Then, as

Kommandeur,

he led

I/JG 77

from Sicily against Malta, and went on to North Africa. After the fall of Tunisia in the spring of 1943 he was withdrawn from operations with malaria and a stomach ulcer, his score 158.

He returned to combat late that year as

Kommandeur

of

II/JG 1

, on home defence, flying the FW 190 for the first time against the American heavy bombers. With at least 21 claimed, he ranks high among the heavy bomber specialists. His final assignments were as

Kommodore

of

JG 3,

with whom he scored his 200th victory on 22 April 1944; as commander of the jet fighter school at Lechfeld from January 1945, where he flew the He 162; and finally with

JV 44

, which he commanded after Galland was wounded and Günther Lützow (108 victories) was killed.