Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (32 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

The

Komet

was a point-defence interceptor powered by a liquid-fuelled rocket motor. While this gave a maximum speed far in excess of any piston-engine fighter, and a rate of climb more than twice as great, it used fuel at a fantastic rate. Even though the fuel load carried exceeded the empty weight of the aircraft, it gave a maximum of only eight minutes’ endurance, and rather less if full throttle was used throughout the flight.

To minimise weight and thus maximise performance, the

Komet

did not have conventional landing gear: it took off from a wheeled dolly and landed back on a retractable skid. On a bumpy surface this was often hard, and back injuries to pilots were commonplace.

Two fuels were used, one of which was extremely corrosive, and pilots wore special resistant overalls. When in contact with one another, they ignited hypergolically. The mixture was very unstable, and the slightest leakage could result in an explosion. Accidents of this nature were frequent: the

Komet

killed more of its pilots than ever did the enemy.

In the air the

Komet

handled well, despite its unorthodox tailless configuration. Operationally it had to be held on the ground until the last minute, but when it was finally launched, its sparkling rate of climb took it to the altitude of the bombers in only two or three minutes. The

smoke plume from its efflux meant that its approach could not be concealed, but it was too fast to be intercepted by conventional fighters. Once the fuel ran out, it became a glider. This was not quite as suicidal as it sounds. Even with power off, the

Komet

could be dived at speeds exceeding 500mph, whilst above 250mph it was remarkably agile. The real problem was getting it back to the airfield—and having to land at the first attempt.

Experten

known to have flown the

Komet

were Wolfgang Späte (99 victories, mainly Eastern Front, plus five later with the Me 262) and Robert Olejnik (41 victories). The latter developed tactics for the

Komet

which involved roller-coasting through a bomber formation, going first over, then under each target in succession. On one occasion he accounted for three B-17s in a single sortie by this means, but shortly afterwards was badly injured in a landing accident.

If the

Komet

could have been made reliable, it could have been an effective point defence interceptor. But, while it entered service with

JG 400

, it achieved little.

The only really effective German jet to see service was the Me 262, and this was limited by the short life and unreliability of its engines. Given the low thrust of the early turbojets, the choice was to go for a light and simple single-engine fighter such as the He 162 or produce a twin-engine design. In the case of the

Schwalbe

, the latter course was chosen. Two Junkers Jumo axial-flow turbojets were mounted under-slung on the wings. With hindsight, that invaluable aid to decision-making, if the engines had been mounted side by side beneath the fuselage, the Me 262 might have been a better fighter. This configuration would have minimised problems of asymmetric handling, always a factor with unreliable engines, and have improved performance in the rolling plane.

Our

‘

ground school’ lasted one afternoon. We were told of the peculiarities of the jet engine, the dangers of flaming out at high altitude, and their poor acceleration at low speeds. The vital importance of handling the throttles carefully was impressed upon us, lest the engines catch fire. But we were not permitted to look inside the cowling of the jet engine

—

we were told it was very secret and we did not need to know about it!

Walther Hagenah,

III/JG

7

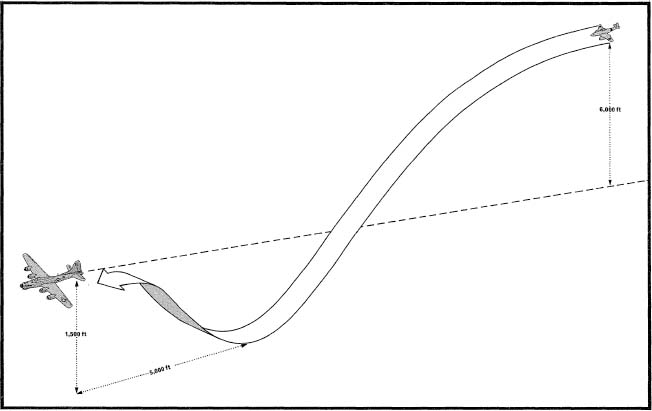

Fig. 25. The Roller-Coaster Attack

To attack American bombers, Me 262 pilots started from a position high astern. A shallow highspeed dive took them through the escorts to a point about one mile astern of the bombers and l,500ft below them. At this point they pulled up to dump speed and carried out a conventional rear attack before breaking off downwards.

But this is with hindsight, and it didn’t happen. One of the myths that have grown up around the Me 262 was that, had Hitler not seen it as a bomb-carrier, it could have been in service as a fighter much earlier. In fact, the

Führer

’s intervention cost a mere three weeks.

The great strength of the Me 262 was its overwhelming speed, which allowed it to penetrate the American escort screen with relative impunity. Its weaknesses were legion, even when the engines worked as they should. If an Me 262 could be forced to turn hard to evade, it bled off speed and became vulnerable. After take-off, only slowly did it reach fighting speed, during which time it was vulnerable to enemy fighters. The basic armament consisted of four 30mm cannon. While these gave tremendous hitting power, the relatively low muzzle velocity meant that accurate shooting depended on getting to close range. Inevitably this brought the jet well inside the lethal range of return fire from the American bombers.

Like all early jet engines, the Jumos were thirsty, and an average sortie lasted less than an hour. Nor was the Me 262 able to slow down quickly. To land it needed a long, straight approach, bleeding off speed as it went. During this time it was vulnerable and Allied fighters took to patrolling the approaches of known Me 262 airfields. Many Me 262s were lost in this way.

in Action

The first Me 262 unit was

Kommando ‘Nowotny’

, which commenced operations in July 1944. This was very much an operational trials unit, and problems with the under-developed engines ensured that rarely were more than four aircraft serviceable at any one time. Not until September was the Jumo 109–004 sufficiently advanced to enter mass production, and even then its life was short. Pilots had to fly the engines at least as much as the aircraft in order to keep temperatures within limits. The take-off sequence was as follows:

Line up and apply both brakes. Set trim for 3 degrees nose-down, and flaps at 20 degrees. Start stopwatch. Open throttles to 7,000rpm, then release brakes and open throttles fully. Lift off between 175 and 200kph, with a gentle pull on the stick. Too hard a pull resulted in a high an angle of attack, with a consequent increase in drag which the

slow build-up of thrust might not be able to overcome. Brake wheels and retract undercarriage, avoiding exceeding 260kph while doing so. Retract flaps before speed reaches 360kph, then trim for normal flight. Engine revs for cruising: 8,000–8,300.

Once the 262 was in the air, the engine instruments and fuel gauges had to be monitored constantly. If the throttles were handled injudiciously, compressor stalls and flame-out followed, while if the turbine temperatures rose too high fire was the normal result. To quote Adolf Galland on the subject, The best thing was to go to a certain point and leave it, and then fly, and throttle back only when you are going to land.’ In combat, hard manoeuvring with high angles of attack was avoided. Not only could this cause compressor stalling, but the increase in induced drag bled off speed at an alarming rate, which could only slowly be recovered. Once the speed advantage was lost, the

Schwalbe

was vulnerable to conventional fighters.

Landing was an equally delicate operation. First the engines were throttled back to 6,500rpm. Speed was then reduced to between 360 and 320kph. This was done by raising the nose to increase drag; at reduced power the aircraft continued to sink. Lowering the undercarriage made the Me 262 tail-heavy; this had to be trimmed out, and speed reduced to 300kph. Twenty degrees of flap was then selected. To turn, speed could not be allowed to fall below 280kph without risking loss of control.

According to the instruction manual, single-engine flight was quite possible, and turns could be made both into and against the dead engine. If the first landing approach was botched, an overshoot was theoretically possible, but, given the need to advance the throttles slowly, coupled with poor acceleration at low speed, this was obviously a marginal undertaking.

The Me 262 equipped reconnaissance and bomber units during the war and several small specialist units such as

Kommando

‘

Nowotny

’, but only a handful of fighter units. These were all three

Gruppen

of

JG

7, and

I/KG(J) 54

, which employed bomber pilots because they were well used to instrument flying and could thus operate in adverse weather

conditions. The argument was that it was quicker to train bomber pilots to fly fighters than to give instrument training to fighter pilots.

10/NJG 11

was the sole jet night fighter

Staffel.

Finally there was the famous

JV

(Jagdverband) 44,

composed entirely of

Experten.

Although the Allies had encountered the Me 262 in action from the late summer of 1944, the fact was that by the second week in January 1945 not one day fighter unit was operational. Not until 9 February did the new jet operate in force, and even then the day ended in disaster. Ten ex-bomber pilots of

IIKG(J) 54

intercepted a massive American bomber raid, only to lose six jets to Mustangs. Just one B-17 was damaged.

Rudolf Rademacher of

III/JG

7, lately of the ‘

Nowotny Schwarm

’, scored all his eight jet victories during February. They consisted of a reconnaissance Spitfire, a Mustang, five B-17s and a B-24. But few were so lucky. Then, towards the end of the month,

JV 44

was formed under the command of Adolf Galland. This was an élite unit in the truest sense of the term. Members included Gerd Barkhorn (301 victories), Heinz Baer (220),

‘Graf

Punski’ Krupinski (197), ‘Macky’ Steinhoff (176), Günther Lützow (108 victories) and Heinz ‘Wimmersol’ Sachsenberg (104). A galaxy of stars also gravitated to the much larger

JG

7, among them Erich Rudorffer (222), Heinrich Ehrler (209), Theodor Weissenberger (208) and Walter Schuck (206). It was this unit which delivered the first large-scale Me 262 attack on 3 March 1945 when 29 jet sorties were flown against the American ‘heavies’. Claims were six bombers and two fighters, for a single Me 262 lost.

On several occasions that month, between 20 and 40 jets tackled heavily escorted formations of over 1,000 bombers. The results showed what several hundred jet fighters might have achieved. Two notable

Experten

from

JG

7 paid the ultimate price during this period. They were Hans ‘Dackel’ Waldemann (134 victories), who collided with another Me 262 in fog on 18 March, and Heinrich Ehrler, who fell to return fire from the bombers on 4 April.

Not until 5 April did

JV 44

fly its first sorties, and by that time the situation was so desperate that only a handful of aircraft could be scrambled at any one time. Galland’s élite band could do no more than nibble at the fringes.

Experten

The Me 262 came late into action, and virtually all its missions were flown against incredible odds. Only a handful of

Experten

scored double figures in the jet. But, bearing in mind the military situation at that time, this was a remarkable achievement. To digress for a moment, the German jet top score of 16 has only once been exceeded (by one), by an Israeli pilot almost thirty years later.

JOHANNES ‘MACKY’ STEINHOFF

Only six of ‘Macky’ Stein-hoff’s 176 victories were with the Me 262, but as

Kommodore

of

JG

7, the first ever jet fighter

Geschwader

, charged with evolving tactics suitable for the new type, he is arguably the

Experte

who had the greatest influence on its subsequent operations.

Steinhoff commenced the war as

Staffelkapitän

of the night-flying

10/JG 26,

equipped with Messerschmitt Bf 109Ds. This notwithstanding, his first victory occurred in daylight, a Wellington bomber on 18 December 1939. As related earlier, he then transferred to day fighters. He led

4/JG 52

throughout the Battle of Britain, then took part in the invasion of Russia with this unit. Steinhoff’s 150th victory came in February 1943, then in the following month he was posted to

JG 77

in Tunisia as

Kommodore.

With this unit he had the unenviable task of supervising two evacuations in quick succession, first from North Africa and then from Sicily. In December 1944 he was appointed to command

JG

7.

Steinhoff’s first task was to prepare his new unit for operations. An early innovation was to drop the four-aircraft

Schwarm

in favour of the three-ship

Kette.

This was a matter of convenience. The Me 262 could not operate from grass fields, only from long, hard-surfaced runways. At a pinch, three Me 262s could line up abreast on a standard runway for a formation take-off. Whereas the

Schwarm

had been adopted for mutual cover, sheer speed could protect the Me 262 against attack from astern. As we saw earlier, Egon Mayer of

JG 2

used the

Kette

against the ‘heavies’, ceasing only when escort fighters made it impractical.