Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (28 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

During 1944 he scored 64 victories—a record unequalled by anyone—many at a time when the

Nachtjagdflieger

was outnumbered and technically overmatched. His final fifteen victories came in 1945, nine of them in one 24-hour period on 21 February, giving him a total of 121. His secret was superb aircraft handling combined with marksmanship (three victories were scored against violently corkscrewing bombers) and Rumpelhardt on the radar. Schnaufer flew only the Bf 110. He survived the war but died in a road accident in France in 1950.

| 9. OVERLORD TO GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG |

Spring 1944: the German High Command knew full well that before long the Allies would launch a huge amphibious attack across the Channel, although they could only guess at where and when. Equally, they knew that their only chance was to halt it on the beaches. With the Reich under air attack by day and by night, they were unable to release

Luftwaffe

units to strengthen the area beforehand: they were forced to rely on contingency plans to rush reinforcements in once the invasion started.

In the preceding months the Allies had started to soften up the defences of Fortress Europe. Road and rail systems, communication and command centres, radar stations—all were targeted, as well as the more obvious troop concentrations and supply depots. This was done over a wide area so as to give no clue as to where the landings were to take place. Tactical bombers and fighter-bombers roamed the skies of France and the Low Countries, their fighter escorts never far away.

A softening-up of the

Jagdwaffe

was also part of the plan, although the general level of Allied air activity was so high as to make it seem almost incidental. In the 61 days between 6 April and 5 June 1944, 98,400 Allied counter-air sorties were flown, against which the

Jagdwaffe

could pit only 34,500. Allied fighter losses to all causes were 1,012. This was high, but with both aircraft and pilots streaming off the production lines, it was affordable.

Jagdwaffe

losses were even higher, at 1,246. The German aircraft industry was performing minor miracles at the time, and the fighters could be replaced. The flying schools still turned out pilots, but they were green and under-trained. Not only were they inadequate as replacements for the ‘old heads’, but they were no match for the better-trained and aggressive Allied fighter pilots. Few survived their first

half-dozen sorties. Worse still, many high-scoring

Experten

went down during this period, and these were irreplaceable.

In the face of overwhelming air superiority,

Luftwaffe

reconnaissance failed to detect not only the massing of the vast invasion fleet on the south coast of England, but its sailing. Not until the landings were under way did the German High Command realise the fact, and even then they were slow to react. Only about a hundred sorties were flown on the first day, against an Allied air umbrella of more than 3,000 fighters flying in relays. Nor did the reinforcement plans work as advertised. As Adolf Galland later commented,

When the invasion finally came, the carefully made preparations immediately went awry. The transfer of the fighters into France was delayed for 24 hours because

Oberkommando West

would not give the order, expecting heavier landings to be attempted in the Pas-de-Calais area. The

Luftwaffe

finally issued the order on its own authority, and the transfer began.Most of the carefully prepared and provisioned airfields assigned to the fighter units had been bombed and the units had to land at other hastily chosen landing grounds. The poor signals network broke down, causing further confusion. Each unit’s advance parties came by Junkers 52, but the main body of ground staff came by rail, and most arrived days or even weeks later.

Worse was to come. Over the next 90 days, the Allies put up the massive total of 203,357 fighter sorties, against which the

Jagdwaffe

could muster only 31,833, a more than 6:1 disparity which was reflected in the casualty list—516 Allied fighters lost to all causes against 3,527 German fighters. Many of the latter were destroyed on the ground by strafing, but the loss was still tremendous. Four high-scoring

Experten

were killed in the first three days of the invasion. Karl-Heinz Weber of

II

/

JG 1

(136 victories, all in the East), was shot down south of Rouen. The others were Zweigart (69 victories), Hüppertz (68) and Simsch (54), all of whom had flown extensively in the East.

Some units were decimated. About 40 FW 190As of

II

/

JG 6

surprised a dozen Lightnings in the act of strafing an airfield near St Quentin and shot down six in short order. Then two more squadrons of Lightnings arrived on the scene. In the mêlée that followed, one more Lightning went down, but so did sixteen Focke-Wulfs, with others damaged. On paper, the German fighter was more than a match for its twin-engine opponent, but in practice German pilot quality was so poor as to reverse

the situation. Shortly afterwards,

II/JG 6

was withdrawn from the front. It was far from being the only one.

Three centurions had fallen by the first week in September. Josef ‘Sepp’ Wurmheller of

III

/

JG 2

(102 victories, of which 93 were in the West) collided with his

Kacmarek

during a dogfight on 22 June. Otto Fonnekold of

II

/

JG 52

(136 victories, mainly in the East) was caught during his landing approach by American fighters and shot down. Emil ‘Bully’ Lang was the greatest loss. Widely regarded as the bravest man in the

Luftwaffe,

he scored 148 victories in the East, including a purple patch of 72 in less than three weeks at the end of 1943. This included eighteen in one day, making him the only man to surpass Marseille in the annals of mass destruction. Transferred to home defence, Lang continued scoring, and he became

Kommandeur

of

II

/

JG 26

in June 1944. By 3 September he had raised his score to 173, when he encountered Thunderbolts over Belgium. An unlucky hit on his hydraulic system caused his wheels to drop; thus handicapped, he was quickly shot down and killed.

As the Allied armies poured across Europe, the

Luftwaffe

was constantly forced to retreat through a succession of temporary landing grounds, harassed the while by Allied fighters which frequently moved into airfields just vacated. Confusion was high: on occasion the

Jagdflieger

were unable to locate their newest bases from the air and landed where they could. Logistics and communications were chaotic and ground control virtually non-existent, while from August operations were restricted by fuel shortages. The

Jagdwaffe

in the West was a spent force, its strength diminishing daily.

Help was at hand, and from an unexpected source. By early autumn the logistics problems of maintaining the huge Allied armies were outrunning their supplies. Gradually the offensive stalled, and with this the urgency of defensive air operations was reduced. The

Jagdwaffe

used the breathing space well. Bases were reorganised, fuel stocks were laboriously built up, and each

Jagdgruppe

was expanded to four

Staffeln.

New aircraft were in plentiful supply, and fifteen

Jagdgruppen

were completely re-equipped. The main cloud on the horizon was the dearth of trained fighter pilots, and the numbers were made up with men drawn from disbanded bomber units.

By now one thing was clear. The American bombing raids had to be stopped.

General

der Jagdflieger

Adolf Galland produced an ambitious scheme to achieve just this objective. He reasoned that if 400-500 bombers could be shot down in a single day, the USAAF would be forced to call a halt, giving the Reich a valuable breathing space. To do this, he assembled a force of eighteen

Jagdgruppen

with over 3,000 fighters. By 12 November all was ready. It was just a question of waiting for suitable weather.

It was not to be. Many fighters were frittered away in supporting the abortive Ardennes offensive. Even more were squandered in

Operation

‘

Bodenplatte’,

the New Year’s Day attack on Allied airfields by about 900 fighters. About 200 Allied aircraft were written off on their airfields, but German losses were nearer 300. The difference was that, whereas few Allied pilots were lost, the

Luftwaffe

pilot casualty list was 237 killed, missing or taken prisoner and eighteen more wounded. To make matters worse, twenty of these were experienced leaders, among them Horst-Günther von Fassong of

III/JG 11

(about 136 victories, mainly in the East), who was shot down by Thunderbolts near Maastricht, Heinrich Hackler of

II/JG 77

(56 victories), missing near Antwerp, and the very experienced, one-eyed Günther Specht,

Kommodore

of

JG 11

(score unknown, but at least 32 in the West, including fifteen heavy bombers), who fell to flak near Brussels.

The

Jagdwaffe

never recovered. Opposition to the daylight incursions of the USAAF noticeably weakened. Great hopes were pinned on the new jet fighters (see Chapter 11). As these were too fast to be caught by propeller-driven fighters, the Allies took to lurking in the vicinity of known jet airfields in the hope of catching them at slow speeds shortly after take-off or while preparing to land. Consequently the new wonder fighters needed protection at these times, and piston-engined

Jagd-gruppen

were assigned to the task of patrolling the airfield approaches. Had the jets scored a series of dazzling victories, this would have been effort well spent. As it was, it is debatable whether or not this was a misuse of conventional fighters.

With British, American, Canadian and French armies closing from the West, and the Russians from the East, the war, clearly, was lost.

Jagdflieger

morale slumped. Pilot quality, the ultimate arbiter in fighter

combat, was reflected in the results of the engagements that took place, while many of the more successful pilots were transferred to the new jet formations. Those still flying conventional fighters in the West frequently came off worst, often because they were outnumbered, but not always. To quote but one example, on 25 February fifteen Bf 109Gs of

I/JG 27

were attacked by eight Tempests. In the ensuing mêlée they shot down one Tempest but lost four aircraft and four more damaged. In the final weeks, units sometimes avoided combat. When it was forced on them, they fought hard, but to little avail.

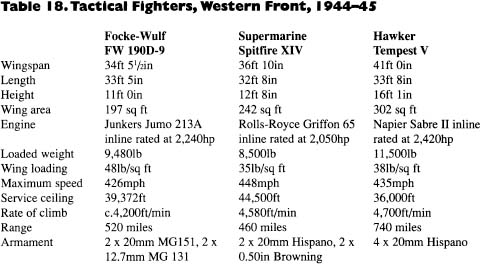

The conventional German fighters of this period were the Messerschmitt Bf 109G and Focke-Wulf FW 190A, both in their later variants. The latter was, however, developed into the ‘Dora’ —the FW 190D-9—and its high altitude counterpart, the Ta 152, although very few of the latter entered service before the end of the war.

The ‘Dora’ entered large-scale service in the autumn of 1944. Outwardly it was still recognisable as an FW 190, but it differed from them in having an extended nose which housed a Junkers Jumo 213 A inline engine, ahead of which was an annular radiator which gave the impression of a radial. Water-methanol injection was used to boost power for short periods. To compensate for the extra nose length, the fuselage was stretched and the tail surfaces enlarged. The standard armament was two 20mm MG 151 cannon in the wing roots and two 12.7mm MG 131 machine guns above the engine.

At first its pilots were a little suspicious of their new mount. The rate of roll was slower than the radial-engine variant, and the extra length made it sluggish in pitch. However, it had its virtues. It accelerated better, was faster, and had a better dive and climb performance than its predecessor, which was really saying something. Whereas its radius of turn was no better than that of the A-8, it did not bleed off speed so quickly. To its Allied opponents it was universally known as the ‘Long-Nose’, and treated with great respect.

The American fighters were primarily the Thunderbolt and Mustang, described in Chapter 7, while the Spitfire IX was still in widespread use with the RAF. British newcomers were the Spitfire XIV, a very potent

Griffon-engine variant which entered service early in 1944, and the Hawker Tempest V, which arrived at the front later that year. The latter was optimised for air superiority at low and medium altitude. A big machine, it was nevertheless very fast and very agile.