Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (12 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

The invasion of the Soviet Union, code-named ‘Barbarossa’, took place shortly before dawn on 22 June 1941. Surprise was total. With many airfields unusable due to construction work, those that were operational were crammed with aircraft, lined up wingtip to wingtip as though for inspection. They made a wonderful target. So many were they that some

Luftwaffe

pilots felt certain that the Russians had planned a mass attack, which they themselves had pre-empted. This was of course to ignore the fact that air bases on a war footing would have had their aircraft dispersed and camouflaged. As it was, there was little opposition from flak, and virtually none from fighters. When the bombers had finished their work, the

Jagdflieger

strafed anything that was left.

The destruction was enormous, but the huge number of Russian airfields ensured that they could not all be attacked by the first wave. The second attack, launched as soon as the German aircraft were refuelled and rearmed, found Russian fighters in the air and ready. Savage dogfights erupted, in which the slow but manoeuvrable Soviet fighters caused the

Jagdflieger

many problems. Franz Schiess of

Stab/JG 53

(total score 67 victories) later recalled: ‘They would let us get almost into an aiming position, then bring their machines around a full 180 degrees, till both aircraft were firing at each other from head-on!’

We hardly believed our eyes. Row after row of reconnaissance aircraft

,

bombers and fighters stood lined up as if on parade. We were astonished at the number of airfields and aircraft the Russians had ranged against us.

Hans von Hahn,

Kommandeur I/JG 3

(total victories 34)

Against the Polikarpov I-16 Type 24, armed with two 20mm ShVAK cannon, this was not a good place to be. Compared with the German 20mm MG FF, the Russian weapon had a muzzle velocity nearly 50 per cent greater, well over double the rate of fire and a rather heavier projectile. Given accurate aiming, the greater effective range and weight of fire were to the advantage of the Russians, but poor training and in many cases the absence of a proper gunsight (some Russian aircraft carried only a painted circle on the windshield) redressed the balance.

What the Russian fighter pilots lacked in finesse they endeavoured to make up in sheer doggedness. On many occasions German aircraft were destroyed by ramming, and frequently the Soviet pilot survived to fight again. It was a different matter with their bombers and attack aircraft, which, in the early days, came again and again in small formations with no fighter escort. They were mercilessly hacked from the skies.

Luftwaffe

claims for the first day were 1,489 aircraft destroyed on the ground and 322 in air combat or by flak. The Soviet Official History admits 1,200 lost, of which 800 were on the ground. That the Soviet Air Force was far from wiped out on the ground is evident from the number of air victories claimed, added to which they flew over 6,000 sorties on the first day—hardly the sign of a beaten force.

There can be no doubt that the first day of ‘Barbarossa’ was a victory for the

Luftwaffe.

Nevertheless, it carried within it the seeds of defeat. While the destruction of aircraft on the ground was important, their pilots were untouched. In the final analysis, this was critical. A surplus of trained pilots made the task of forming new units, equipped with new and better fighters, a simpler matter than might otherwise have been the case.

The months that followed were a ‘happy time’ for the

Jagdflieger

, and many

Experten

began to run up enormous scores. Werner Mölders exceeded

Richthofen’s First World War score of 80 victories on 30 June and went on to reach his century by 15 July, the first fighter pilot ever to do so. Lagging him by three months were Günther Lützow, who achieved this mark on 24 October, followed two days later by Walter Oesau.

Fighter pilots are by nature competitive, and in some units the race for victories during this period almost amounted to a fever. Several factors influenced this. The poor quality of the opposition, both pilots and aircraft, plus a high volume of Russian sorties, combined to form a target-rich environment.

The Germans had mobile radar sets and an

ad hoc

reporting system; the Russians had virtually nothing. The result was a series of encounter battles as one or other tried to support their respective ground forces. Generally these took place at medium and low levels, as opposed to the ‘ever higher’ trend evident during the Battle of Britain the previous year. Moreover, many of the lessons of that conflict were promptly ‘unlearned’. The poor quality of most Soviet pilots bred contempt. Whereas most German pilots would have hesitated before trying to out-turn a British-flown Spitfire, they now entered into dogfights against numerous opponents without a second thought. It was an attitude that bred carelessness that eventually cost them dear.

Four other factors played a part. The first was that, as the penetration into Russia deepened, so the front widened. There was more ground to cover—fewer fighters per hundred miles of front. Secondly, difficulties in North Africa caused units to be detached there at the expense of the Eastern Front. These two factors resulted in the

Jagdwaffe

being increasingly used as a fire brigade and rushed to wherever the need was greatest. Thirdly, as the advance continued, lines of communications lengthened, increasing logistics problems. Fuel and spares were often in short supply and serviceability declined. The inevitable result was a dilution of effort, while the Soviet Air Force was daily growing stronger. The final factor was ‘General Winter’, who halted the German advance just short of Moscow and, far to the south, short of the Caucasian oilfields.

With the onset of winter, accidents caused by poor weather and icing proliferated, while the piercing cold froze engines and made flying almost impossible. This last problem was solved by captured Soviet personnel.

The Russians were used to extreme conditions, and had overcome most difficulties with measures that by Western standards were unduly hazardous. The freezing of engine oil was countered by adding neat petrol to the mixture to thin it; this quickly evaporated when the engines were warmed up. Warming the engines to prevent them from freezing solid was done by lighting open petrol fires beneath them. Surprisingly, this caused few disasters.

The spring of 1942 saw the Germans advancing once more, east towards Stalingrad and south towards the Caucasus oilfields. After some early successes they were halted by Russian counter-attacks and finally driven back, while the 6th Army under von Paulus was encircled outside Stalingrad and eliminated early in 1943. It was the beginning of the end. After enduring another harsh winter, the German armies were driven back in the first six months of 1943, the summer of which climaxed with the decisive Battle of Kursk.

German fighter pilots generally admit that aerial victories were easy to come by in 1941, rather more difficult in 1942, and even harder by 1943. The reasons are obvious. The Russian fighter arm underwent a tremendous improvement over these years, both in quantity and quality. The qualitative improvement was not just in aircraft but also in pilots. The first year of the Great Patriotic War was a learning time for the Russians. Not only were they quick to adopt the ‘Finger Four’ formation, but, with ace pilots like Alexsandr Pokryshkin analysing and improving tactics, they became far more effective. Nor was that all. A close air support aircraft, the Ilyushin II-2, was introduced. Heavily armoured, it gained a reputation for being difficult to shoot down. On one notable occasion a

Jagdgeschwader Kommodore

, seeing an entire

Schwarme

attack an II-2 with no visible result, asked ‘Whatever is going on down there?’, only to draw the classic reply,

‘Herr Oberst

, you cannot bite a porcupine in the arse!’

While the Russians grew stronger, the

Jagdflieger

grew weaker. By 1943 only four

Jagdgeschwader

were deployed on the 2,000-mile (3,200km) Eastern Front, and of these

JG 5

had only two

Gruppen.

This amounted to one fighter approximately every five miles! Pilot quality

also declined. Death, wounds or simply fatigue reduced the number of ‘old heads’, and their replacements were no substitute. For each

Experte

piling up victories, dozens of young pilots arrived at the Eastern Front, flew a handful of fruitless missions and then vanished as though they had never existed. For example, one

Jagdgeschwader

lost 80 pilots over quite a short period and, of these, 60 had failed to score.

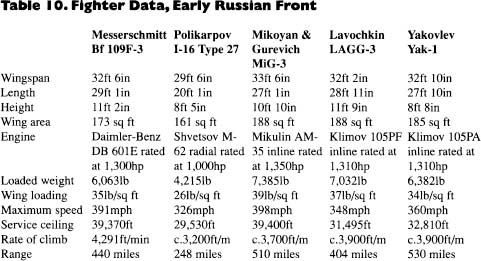

German fighters of this period differed little from those used in the Battle of Britain a year earlier. The Bf 109E and the twin-engine Bf 110C were still in service, supplemented by the much improved Bf 109F. This last was an extensively revamped 109E fitted with the Daimler Benz DB 601E-1 engine rated at l,300hp, housed in a completely redesigned symmetrical cowling. A larger spinner covered the boss of the propeller, which was six inches (15cm) smaller in diameter than that of its predecessor. On the left side of the cowling was a very prominent supercharger intake, so positioned to increase ram air effect. At the other end of the aircraft, a cantilevered tailplane eliminated the need for the bracing which had been one of the distinctive features of previous 109s. The tail wheel was made retractable and the wings and flying surfaces underwent extensive revision, including increased span and rounded tips.

The armament of the Bf 109F was controversial—a single 20mm (15mm in the F-2) MG 151 firing through the propeller boss and two rifle-calibre MG 17s in the wings. While the higher rate of fire and greater muzzle velocity made it far superior to the MG FF, a single cannon was regarded as a retrograde step in many quarters. Werner Mölders favoured the lighter armament but Adolf Galland was strongly against it. Be that as it may, the Bf 109F was faster and more manoeuvrable than its predecessor, making it more suitable for conditions at the Russian Front.

The Russians used several different fighter types during this period. Numerically, the most important in service was the Polikarpov I-16, but at the time of ‘Barbarossa’ the Mikoyan MiG-3, Lavochkin LAGG-3 and Yakovlev Yak-1 were all entering service. While large numbers of British and American fighters were supplied to Russia, notably the Hurricane and Airacobra, these four indigenous types bore the brunt of the early fighting.

First flown on the final day of 1933, the I-16 was a world leader in fighter design. Conceived in the biplane era, it was a low-wing cantilever monoplane with an enclosed cockpit and a retractable undercarriage. Powered by a nine-cylinder radial engine, by 1941 it was hopelessly outclassed in performance by the German fighters, but it had other virtues. It was small and basically unstable; in combat this added to its agility. Its heavy armament has already been mentioned.

The MiG-3 was designed as a high-altitude interceptor. Powered by a twelve-cylinder inline engine, it was a very sleek machine, able to combat the Bf 109 at medium and high altitude, although less so lower down due to its high (for the time) wing loading. Armament was on the light side—a single 12.7 and two 7.62mm machine guns. Soviet ace Alexsandr Pokryshkin gained the majority of his 59 victories with the MiG-3.

The LAGG-3 bore a vague external resemblance to the American P-40 Tomahawk. It was largely of wooden construction, including birch ply skinning. Its acceleration was poor, and it had a tendency to stall and spin during hard manoeuvring. This inhibited its pilots in the dogfight, although it was later found that lowering a few degrees of flap countered this tendency. Armament varied, but the usual fit was a

single 20mm cannon and two 12.7mm machine guns, all mounted in the nose.

Best of all was the Yak-1. An aerodynamically clean design, it differed from its contemporaries in having a steel tubing fuselage, although much of the skinning was of birch ply. Fast and very manoeuvrable, it was the ancestor of a whole family of successful Yakovlev single-seat fighters. Like most Soviet aircraft of the period, it was lightly armed, the usual fit being one 20mm cannon and two 12.7mm machine guns in the nose.

Experten

The leader in the early days of the Russian campaign was Werner Mölders who, after a short time at the front during which he became the first pilot in history to achieve 100 victories, was promoted to command the

Jagdwaffe.

This threw the race wide open. Many future high scorers were prominent at this time, but the first man to achieve 150 victories, on 29 August 1942, was former

Zerstörer

pilot Gordon Gollob. Of these, no fewer than 144 were on the Russian Front. Gollob, an Austrian with a Scottish father (McGollob) was then promoted to become a Fighter Leader in the West, and did not return to operations. He finally succeeded Adolf Galland as General of the Fighters in January 1945.