Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (11 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

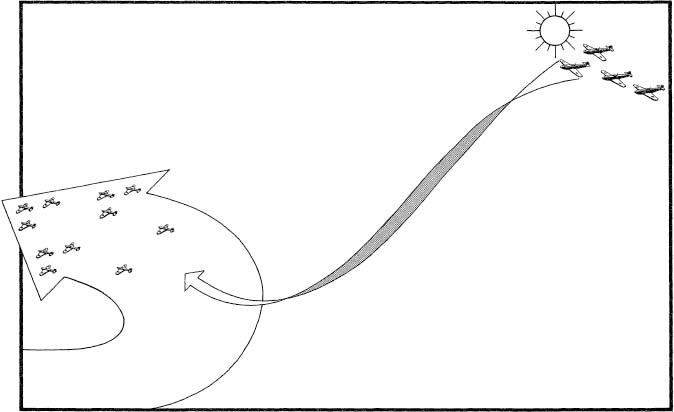

Fig. 11. Galland’s Favoured ‘Up and Under’ Attack

The vast majority of Adolf Galland’s victories came by this means. A steep plunge from astern was followed by an attack coming up in the blind spot astern and below. While not specifically stated, this was best made from a few degrees to the right: the average fighter pilot, his left hand on the throttle and his right on the stick, could look over his left shoulder more easily than his right.

Experten

Fighter pilots differ from most other warriors in that there is a practical, as opposed to a subjective, yardstick by which their deeds can be measured. This is the number of aerial victories they score. To pre-empt comments about overclaiming, the author wishes to stress that a victory is not necessarily a kill: it is a combat in which an enemy aircraft appears to be hit, and goes down in such a manner as to make the successful pilot believe that it is a total loss.

The heavy fighting during the Battle of Britain provided many combat opportunities, and the scores

of the

Experten

—who, it must be said, were a small proportion of the whole—almost took on the aspect of a race. Mölders, the leader at the end of the French campaign, was wounded and out of action for about three weeks from late July, during which time Balthasar passed his score. Only when the latter was wounded early in September did Mölders recover his lead. Meanwhile Galland and Helmut Wick had been catching up fast.

Mölders’ score reached 40 on 20 September, followed by Galland five days later and Wick on 6 October. Wick managed to edge into the lead on 28 November but was shot down that same day, his final score at 56. The last day of the year saw Galland in the lead with 58, three ahead of Mölders. Then came Walter Oesau with 39, while Hans-Karl Mayer reached 38 before his death in action on 17 October. Among many others were Hermann-Friedrich Joppien (31, of which five were in France), Joachim Müncheberg (23) and Gerhard Schöpfel (22). The least successful of the

Jagdgeschwader

was

JG

52,

surprisingly as it contained Gerhard Barkhorn (later to score 301 victories in the East but whose Battle of Britain score was nil) and Günther Rall (who achieved little over England but whose final score was 275, also in the East).

Fig. 12. Schöpfel’s Combat, 18 August 1940

Gerd Schöpfel, leading

III/JG 26

in Gallands absence, spotted the Hurricanes of No 501 Squadron near Canterbury. Waiting until they had their backs to the sun, and leaving his

Gruppe

on high, he plummeted down and picked off both weavers and two others without being spotted. Only when hit by wreckage and oil from his fourth victim did he break off the attack.

The leading Bf 110 pilots were Hans-Joachim Jabs of

II

/

ZG 76

and Eduard Tratt of

I

/

EprGr 210,

both of whom claimed 12 victories in the battle. Jabs, possibly the greatest Bf 110 pilot of all, had previously scored six in France, while Tratt’s feat was remarkable in that he was flying

Jabo

sorties at the time. With an eventual score of 38, Tratt became the top-scoring

Zerstörerflieger

of the war.

HELMUT WICK

Apart from natural ability, Helmut Wick had other advantages. His instructor during advanced training had been the great Werner Mölders, who was also his

Staffelkapitän

in

I

/

JG 53

from March 1939. Shortly after the beginning of the war he was transferred to

I/JG

2, and he scored his first victory on 22 November 1939. But only with the

Blitzkreig

did his score start to mount. He early showed a talent for multiple victories, with two French aircraft on 22 May 1940, two British Swordfish torpedo bombers later that month (although these were unconfirmed for lack of a witness) and four Bloch 152s on 5 June and two more the next day. He ended the campaign in third place behind Mölders and Balthasar with a total of 14. He became

Staffelkapitän

of

3/JG 2

Richthofen

in July 1940; thereafter his rise was rapid. He reached 20 victories on 27 August, then on 7 September he was appointed

Kommandeur

of

II

/

JG

2.

Wick was a remarkable natural marksman, with a gift for keeping track of events around him. If he had a fault, it was impetuosity, which often led him to tangle with the better-turning Spitfires and Hurricanes. His personal creed was:

As long as I can shoot down the enemy, adding to the honour of the

Richthofen Geschwader

and the success of the Fatherland, I am a happy man. I want to fight and die fighting, taking with me as many of the enemy as possible.

Wick got his wish. He was promoted to

Kommodore

of

JG 2

on 19 October 1940 and his score mounted. He claimed three victories on 5 November and five more the following day. On 28 November he finally passed Mölders’ score to become the top-ranking

Experte.

Later that same afternoon he led his

Stabschwarm

out over the Channel on a

Freijagd.

A skirmish with Spitfires near the Isle of Wight saw his 56th victim go down, then Wick was bounced from astern by a Spitfire. His Bf 109 mortally hit, he baled out but was never found. His attacker, John

Dundas of No 609 Squadron, was almost immediately shot down by Wick’s

Kacmarek

Rudi Pflanz (eventual score 52).

GERHARD SCHÖPFEL

One of the lesser known

Experten

, Schöpfel started the war as

Staffelkapitän

of

9/JG 26.

His first victory was a Spitfire over Dunkirk in May 1940, and he scored 21 more during that year. His greatest day came on 18 August when he personally accounted for four Hurricanes of No 501 Squadron within minutes (

Fig. 12

). This multiple claim is fairly unusual in that each of his victims can be identified beyond doubt and in that all were destroyed in the air—there were no forced landings:

Suddenly I noticed a

Staffel

of Hurricanes underneath me. They were using the English tactics of the period, flying in close formation of threes, climbing in a wide spiral. About 1,000m above I turned with them and managed to get behind the two covering Hurricanes, which were weaving continuously. I waited until they were once more heading away from Folkestone and had turned north-westwards and then pulled round out of the sun and attacked from below.

The influence of Schöpfel’s

Kommandeur

Adolf Galland can be strongly felt here. The spiral climb had two failings: first, it was aerodynamically inefficient; and secondly, sooner or later the formation would have its back to the sun. Schöpfel waited until this happened, then launched a solo attack, reasoning that whereas the

Gruppe

, which he was leading in Galland’s absence, was sure to be seen, a single aircraft might well reach an attack position unobserved. It will also be noticed that, even with the initial altitude advantage, Schöpfel chose to attack from below. Two short bursts accounted for the two weavers, and, closing to short range on the nearest Vic, Schöpfel shot down a third:

The Englishmen continued on, having noticed nothing. So I pulled in behind a fourth machine and took care of him, but this time I went in too close. When I pressed the firing button the Englishman was so close in front of my nose that pieces of wreckage struck my windmill. The oil from the fourth Hurricane spattered over my windscreen and the right side of my cabin so that I could see nothing. I had to break off the action.

Schöpfel succeeded Galland as

Kommandeur

of

III/JG 26

, then again as

Kommodore

of

JG 26

late in 1941, a command he held until January 1943. He survived the war, his final score 40, all in the West..

| 3. BARBAROSSA TO ZITADELLE |

Hitler’s Directive No 21, dated 18 December 1940, opened with the words ‘The German armed forces must be prepared to crush Soviet Russia before the end of the war against England.’ From this moment the die was cast.

Reichsmarschall

Goering, Supreme Commander of the

Luftwaffe

, did his best to dissuade the

Führer

from this course of action, which would leave Germany fighting on two fronts—a situation which had proved disastrous in the 1914–18 war. But to no avail.

Following the campaign of 1939, Poland had been partitioned between Germany and Russia on a line stretching from East Prussia in the north, past Bialystok, Brest-Litovsk (now in Belorus) and Lwow (now in the Ukraine), southwards to the Romanian border. At the same time the Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia were incorporated into the USSR. Stalin, always suspicious of Hitler’s intentions, moved large forces into the territory so gained, close to the new border. The Red Air Force was in the throes of a massive modernisation programme, and in 1941 work began on more than 200 airfields in the region, many of them new.

The Soviet Air Force could muster some 12,000–15,000 operational aircraft in all, of which about 7,000, over half of them fighters, were concentrated in the west of the country and in the occupied territories. Front-line combat aircraft were disposed in 23 air divisions, each with three air regiments, although this could vary. The basic flying organisation was the regiment, with an establishment of 60 aircraft. These were made up of squadrons, each with about 9–12 aircraft, making a Russian squadron roughly equivalent to a German

Staffel.

What were the Russian combat formations worth? In the Winter War against Finland they had showed up very poorly—brave, but lacking both skill and initiative. In part this was due to Stalin’s purges of 1938,

which swept away many able commanders on the grounds of political unreliability. Among these were flyers who had gained experience in the Spanish Civil War, and who, having watched the

Legion Kondor

at work, had recommended the adoption of the pair and four (

pary

and

zveno)

formations for fighter operations. Their recommendations died with them. In consequence, Russian fighter pilots were stuck with the three-aircraft Vic, and learnt that individualism and innovation could be politically dangerous commodities. Pilot quality was on the whole poor, due to inadequate training. But whatever the shortcomings of individuals, the Soviet Air Force was a dangerous opponent by virtue of sheer weight of numbers.

The same could be said of the Soviet Army. Numerically strong, it outnumbered the German Army in tanks alone by about 5 to 1. Defeating it depended heavily on the

Blitzkrieg

form of armoured warfare, proven in Poland and France, which in turn was reliant on close air support. To have any chance at all, Germany had to gain air superiority immediately, then retain it for the duration of the campaign. The war had to be won quickly, before Russia could mobilise her vast manpower and industrial resources. If this were allowed to happen, it was doubtful whether Germany could bring the war to a successful conclusion. And so it proved.

Prior to the attack, German intelligence concluded that Russian strength was 5,700 combat aircraft in the European area, of which 2,980 were fighters. This was a serious underestimate, as aircraft in reserve parks were not included. Against this horde, the

Luftwaffe

could deploy fewer than 2,000 combat aircraft, amounting to nearly two-thirds of total effectiveness. The Reich Air Defence could not be weakened, but many units were quietly redeployed eastwards from the Channel coast, leaving only

JG 2

and

JG 26

to hold the British in play. A single

Gruppe

,

I/JG 27

, was in the Mediterranean.

The plan was to make three armoured thrusts, each in Army Group strength, deep into Soviet territory. When the defending armies had been by-passed, the German forces would wheel in to encircle them as a preliminary to their total destruction. To provide air support each Army Group had an Air Fleet (

Luftflotte)

attached.

Luftflotte I

was allocated to Army Group North, based in East Prussia. Its fighter component was

a single

Geschwader

,

JG 54

, equipped with the Bf 109F. More or less central, based on Warsaw, Army Group Centre was supported by

Luftflotte

2. This disposed eight

Gruppen

of single-engine fighters—

II

and

III/JG 27

with Bf 109Es, and

JG 51

and

JG 53

equipped with the Bf 109F. In addition, two

Gruppen

of twin-engine Bf 110s,

I

and

II/ZG 26

, gave long-range cover. Southern Poland to the Romanian border was the domain of

Luftflotte 4

attached to Army Group South with eight

Gruppen

of fighters. Of these,

JG 3

and

I

and

II/JG 52

were equipped with Bf 109Fs, while

II

and

III/JG 77

, plus

I(J)/LG 2

, flew Bf 109Es. In addition, there were two peripheral Bf 109 units available for action:

III/JG 52

was based in Romania just outside Bucharest, while a single

Staffel

,

13/JG 77

, was in northern Norway near the Russian border. Taking into account unserviceability, plus the fact that some units were below establishment, barely 500 fighters were available.