Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (8 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

Note:

Range is a purely theoretical figure, given for comparison. What really matters is combat radius, which necessarily includes combat time at full throttle, and a margin for delay in landing. The effective combat radius of the Bf 109E was 125 miles—less than one-third of the stated range.

Officially the Battle of Britain opened on 10 July 1940 and terminated on 31 October. In practice things were never this clear cut, although four distinct phases are discernible. The first occupied the period when the

Luftwaffe

was moving to bases in France and the Low Countries, readying itself for an all-out assault. It consisted mainly of attacks on convoys in the Channel or Thames Estuary, coupled with

Frei-jagd

(fighter sweeps) over south-eastern England to probe the defences. The bulk of this effort fell upon

JG

51

, led by Great War ace and

Pour

le Mérite

holder Theo Osterkamp. Only gradually was it reinforced by other fighter units.

Hitler’s Directive No 17, issued on 1 August, stated that the

Luftwaffe

should ‘use all forces at its disposal to destroy the British Air Force as quickly as possible’. This gave rise to the second phase of the battle,

Adlerangriff

, or Eagle Attack, an all-out attempt to destroy Fighter Command with a series of heavy raids on radar stations, airfields and other military targets calculated to bring the RAF fighters to battle. Originally scheduled to commence on 10 August, it was delayed by bad weather.

The third phase commenced in early September, when the full weight of the attack was switched to London in a last vain attempt to neutralise Fighter Command. When this failed, and with autumnal weather in the English Channel unsuitable for major seaborne operations, the planned invasion was called off. Raids on the capital continued until the end of the month. From this point on, the main accent was on the night blitz, and phase four consisted mainly of fighter sweeps and fighter-bomber raids, diminishing with the onset of winter.

How a fighter handles in combat cannot be assessed purely on absolute performance data, although the latter can give strong indications in certain areas. For example, the greater rate of climb of the Bf 109E added to its higher service ceiling indicate that at high altitude it handily outperformed the Spitfire I. It is less obvious that at low level the Spitfire generally had the advantage. But most Battle of Britain combats took place at medium altitudes, because that was where the German bombers were, and at medium altitudes there was little to choose between the two. The Hurricane was generally outperformed by the Bf 109, but below 20,000ft it was far more manoeuvrable. It was very resistant to battle damage, and was a very stable gun platform.

After his return from captivity, Werner Mölders flew captured examples of the Spitfire and Hurricane at the Rechlin test centre. His comments were as follows:

Both types are very simple to fly compared with our aircraft, and childishly easy to take off and land. The Hurricane is very good-natured and turns well, but its performance is decidedly inferior to that of the Bf 109. It has heavy stick forces and is ‘lazy’ on the ailerons.

The Spitfire is one class better. It handles well, is light on the controls, [is] faultless in the turn and has a performance approaching that of the Bf 109. As a fighting aircraft, however, it is miserable. A sudden push forward on the stick will cause the motor to cut; and because the propeller has only two pitch settings (take-off and cruise), in a rapidly changing air combat situation the motor is either overspeeding or else is not being used to the full.

The Spitfires showed themselves wonderfully manoeuvrable. Their aerobatics display

—

looping and rolling, opening fire in a climbing roll—filled us with amazement. There was a lot of shooting, but not many hits.

Max-Hellmuth Ostermann,

III

/

J

G 54

(final score 102)

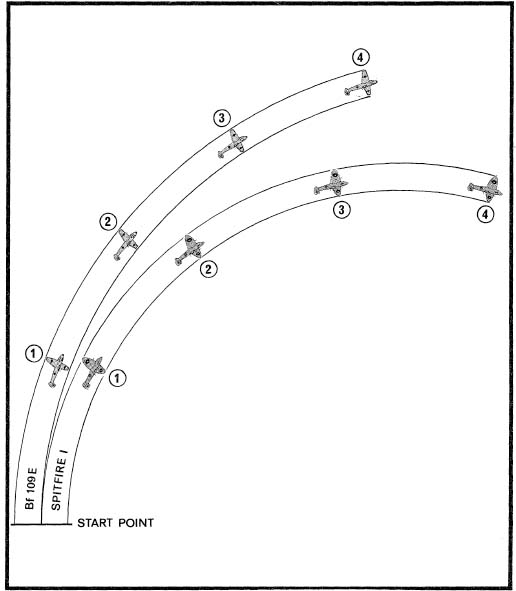

Fig. 9. Comparative Turning Abilities, Bf 109 vs Spitfire I

Seen here to scale are the comparative turning abilities of the Bf 109E and Spitfire I

,

with both turning as hard as they can at the same speed. However, rarely are two fighters co-speed in combat, and the advantage always lies with the attacker.

Given that the wing loadings of both British fighters were about one quarter less than that of the Bf 109E, Mölders’ comments on the turning abilities of the British fighters are hardly surprising, although the reference to the ‘lazy’ ailerons of the Hurricane indicate an altogether slower rate of acceleration into the roll needed to establish the aircraft in a turn. The relatively high wing loading of the German single-seater was to a degree offset by leading-edge slats to increase lift and improve turning ability at speeds approaching the stall, but in tight turns these had the embarrassing habit of opening asymmetrically, affecting lateral stability and making gun aiming difficult. See

Fig. 9

.

The description of the Spitfire as ‘miserable’ stems from the fact that the fuel-injected engines of the German fighters allowed them to bunt into a negative-g manoeuvre without losing power. This provided the

Jagdflieger

with a last-ditch escape manoeuvre that the British fighters could not follow without their engines cutting. To follow a German fighter down, RAF pilots had to perform a time-consuming half-roll and pull-through, during which the 109, with its superior diving qualities, was usually able to pull away out of range. The comment on both British fighters being ‘childishly easy’ to take off and land was very relevant. The Bf 109, of whatever model, was an unforgiving aeroplane. Many aircraft and pilots were lost as a result of take-off and landing accidents. It suffered from incipient swings caused by torque from the engine, and if lifted off the ground too soon tended to roll on to its back. Landings were made power-on. The port wing tended to drop as speed decayed, and adding power at this stage simply made the problem worse. Matters were not helped by the narrow track, rather flimsy undercarriage. Mölders’ final comment, on the two-pitch propeller, was fast becoming irrelevant: a programme was already under way to fit the British fighters with constant-speed units which would improve their performance, particularly in rate of climb.

The Bf 110 was simply too heavy to contend with either the Spitfire or the Hurricane. You had to be lucky to survive.

Hartmann Grasser,

II/ZG 2

(7 victories with the 110, total victories 103)

One area where the opposing fighters differed widely was armament. The

Luftwaffe

fighters mounted a mix of cannon and rifle-calibre machine guns whereas the RAF relied almost exclusively on the latter until the following year. While the weight of fire of the Bf 109E was about 25 per cent heavier than that of the British fighters, the latter could put more than three times as many projectiles in the air in a one-second burst. Against an evading target, this was far more likely to score hits, although, shell for shell, the destructive power of the cannon was much greater. With both sides adopting self-sealing fuel tanks and armour protection for the pilot, one big hit was generally better than three light ones.

The cockpit of the Bf 109 was cramped, and the Revi reflector gunsight was offset to the right, unlike the centrally mounted GM 2 in British fighters. The seat was very low, with the pilot’s legs stretched almost straight out in front of him. This was no bad thing, as it gave added resistance to grey-out in hard manoeuvring. But the real difference lay in the view ‘out of the window’. The side-hinged canopy of the German single-seater was claustrophobic, with heavy metal framing obstructing vision. Rearward view was also poor. This contrasted with the sliding canopies of the British fighters which could be, and often were, pushed back in combat to afford unobstructed vision.

Another point which exercised the

Jagdflieger

was instant visual identification in a multi-bogey fight, with perhaps two or three dozen fighters milling around in a relatively small volume of sky. This was particularly important for units which heavily outnumbered their opponents. Shooting opportunities were often fleeting, and mistakes were all too easily made. To minimise this, some units adopted the famous ‘yellow nose’ to make friendly aircraft more easily identifiable.

The only twin-engine fighter to play a major role in the Battle of Britain was the Messerschmitt Bf 110. In all, nine

Gruppen

of these heavy fighters took part in the battle, while two

Staffeln

of Bf 110s flew with

Erprobungsgruppe 210

in the fighter-bomber role. Initially

Zerstörer

units were regarded as an élite, and many promising young pilots were posted to them. The type did well in Poland as a long-range escort fighter,

and rather less well in France. Now it faced the British air defence system.

The Bf 110 was universally popular with its pilots. Entry was from the left by means of an integral ladder housed in the fuselage aft of the wing. The front canopy was rather complex; the top hinged backwards and the side panels folded down. By German standards the cockpit was roomy. The reflector gun sight was centrally placed and the adjustable seat comfortable. The blind flying panel was adequate for the era, and two dials not found in British aircraft were indicators of cannon and machine gun rounds remaining. Propeller pitch indicators were also featured, and duplicated on the inboard side of the engine nacelles where the pilot could see them in flight.

The inertia starters could be operated from an onboard battery, a ground starter or, if absolutely necessary, by hand. Taxying was simple, with a good all-round view. The take-off run was lengthy, even using flaps. At low speeds the rudders were blanketed by the engines and wings, making directional control poor, while the tail itself was slow to rise. Raising the flaps caused a strong nose-down change of trim, and for safety reasons this was not done until an altitude of 500 feet had been reached.

With the engines set at 2,300 revs, climbing speed was 149mph, a moderately steep angle giving a reasonable rate of climb. In flight the controls were well harmonised, and light up to about 250mph, after which they began to stiffen, particularly the elevator. Turn capability was unsurprisingly less than that of its single-seater stablemate, while rate of roll was considerably worse. In manoeuvre combat it was outclassed by the RAF single-seaters; its sole advantages were high speed at very low level, a rear gunner to guard against surprise and heavier firepower than any other fighter in the battle. Like the 109, it had automatic leading-edge slats which were prone to open asymmetrically.

Landing presented few problems. The undercarriage was lowered before the flaps, the initial deployment of which caused the nose to pitch up. This was countered with forward stick, the pilot relaxing pressure as the flaps came fully down and trim returned to normal. The approach angle was steep, but the forward view from the cockpit was always adequate. Once the aircraft was on the ground, hard braking could be used without any tendency to nose over. This was the fighter in which the

Zerstörerflieger

went to war.

Note:

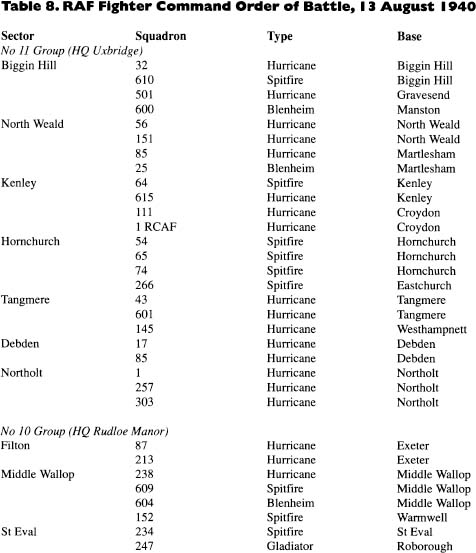

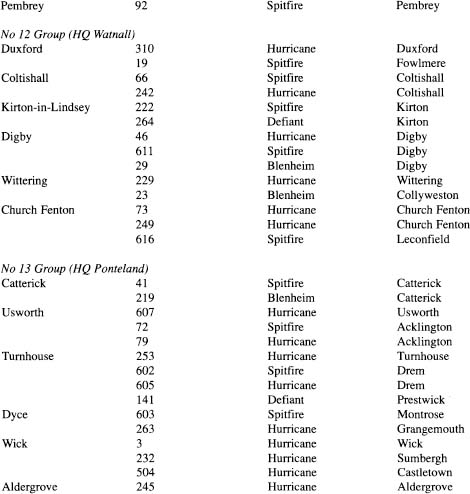

No 263 Sqn were converting to Whirlwinds.