Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (10 page)

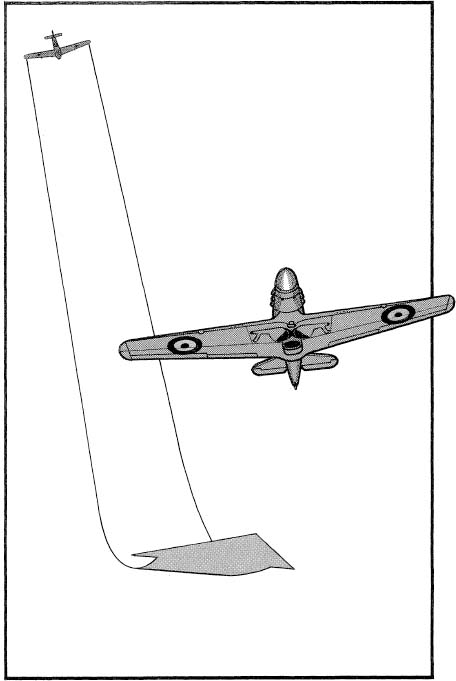

Fig. 10. Typical

Staffel

Formation, Summer

1940

1.

Staffelkapitän;

2.

Schwarmführer;

3.

Rottenführer;

4.

Rottenflieger.

As described by Julius Neumann,

JG 27.

The Bf 110s immediately formed a huge defensive circle, but this time it was a failure. The first Spitfires to arrive swept across the top of it, taking full deflection shots at the

Zerstörer

on the far side. Five Bf 110s fell to this initial attack: with the circle broken the remainder were embroiled in the general mêlée in which one more was lost and five damaged.

Beset on all sides, the

Jagdflieger

desperately tried to keep the fiercely battling Spitfires and Hurricanes away from the bombers; in this they only partially succeeded, even though they were reinforced on the withdrawal by

JG 27.

Six bombers were lost, and seven Bf 109s, making a total of nineteen for this single action. The RAF fighters paid a heavy price, however: sixteen Hurricanes and a Spitfire were destroyed.

The opening attacks of

Adlerangriff

actually took place on 12 August, when the fighter-bomber

(Ja

bo) Gruppe EprGr 210

launched a concerted attack on British coastal radar stations. This was followed by a large raid on the radar station at Ventnor. That afternoon also saw the first attacks on British fighter airfields.

The British radar stations were soon back on the air with the exception of Ventnor, the loss of which was concealed and the gap plugged with a mobile unit. The

Luftwaffe

High Command deduced that radar stations were particularly difficult targets to knock out, and from then on left them pretty much alone. Nor did they ever concentrate on the sector stations with their vulnerable operations rooms. This was an error of the first magnitude, as it greatly reduced the chances of catching the British fighter squadrons on the ground. However, the

Jagdflieger

took an optimistic view, regarding anything that drew enemy fighters up and into combat as an advantage.

In the event, the opening day proper,

Adler Tag,

was an anti-climax owing to bad weather. The score that day was adverse: nine Bf 109s and 18 Bf 110s were lost or force-landed, while twenty bombers were written off. British losses were thirteen fighters, although overclaiming—always such a pernicious feature of air combat—concealed the unpalatable truth from the

Jagdflieger.

Poor weather restricted operations on 14 August, but the next few days saw an all-out assault directed mainly at airfields. This was less effective than expected. Faulty reconnaissance revealed which airfields were in use, but not the aircraft types based on them. Consequently a great deal of effort was wasted raiding bases not used by Fighter Command.

Heavy fighting saw the scores of the

Experten

rise. Galland gained his twentieth victory on 15 August, closely followed by Walter Oesau

(III/JG 51)

and Horst Tietzen

(II/JG

57), although the latter was shot down and killed by Hurricanes near Whitstable on the 18th. Werner Mölders returned to action, and after ten fruitless missions notched up his 27th victory, a Spitfire, on 26 August. Two days later he is recorded as having downed a Hurricane and, rather surprisingly, a Hawk 75, a type not in RAF service. A trio of Hurricanes on the last day of the month put him back in the lead ahead of Balthasar. He need hardly have bothered: the latter was seriously wounded by Spitfires near Canterbury on 4 September and, his score at 31, Balthasar was out of the battle.

Bomber losses in the first six days of

Adlerangriff

totalled 125. Of these, no fewer than 43 were the vulnerable Ju 87 dive bombers, which were withdrawn from operations after a terrible beating on 18 August. The

Jagdflieger

had fought hard to protect them, as witnessed by the loss of 56 Bf 109s and 63 Bf 110s. RAF fighter losses in combat came to just under 100 for this period, although overclaiming fooled

Luftwaffe

intelligence into thinking they were far higher. This notwithstanding, the hard fact was that

Luftwaffe

combat losses were averaging an unacceptable 49 aircraft a day for the first five full days (bad weather on 17 August restricted operations and there were no combat losses on either side).

The German bomber crews complained bitterly about the lack of fighter protection, and instructions were given that in future the majority of the fighters would fly close escort, tied to the bombers to ward off the British interceptors. A further measure taken at about this time was to replace several fighter leaders with young and successful pilots. Adolf Galland, promoted to command

JG 26,

was one of the first to benefit from this change, which took effect right down the line. He was replaced

as

Kommandeur

of

III/JG 26

by Gerhard Schöpfel, and Heinz Ebeling took over

9/

JG 26

from Schöpfel. Other new

Kommodoren

appointed were Günther Lützow to

JG 3,

Hans Trübenbach to

JG 52

and Hannes Trautloft to

JG 54.

The infusion of new leadership in the air appears to have made an almost immediate difference. Although the

Jagdflieger

did not like being tied to the bombers as close escort, claiming with some justification that their advantages of speed, altitude and initiative were being wasted, the fact remains that combat attrition fell to an average of 21 aircraft a day over the final fortnight—a reduction of 60 per cent. Bombers and Bf 110s benefited most: average combat losses for the single-seaters remained at eleven fighters a day! The average loss rate of British fighters remained unchanged at nineteen aircraft a day during this period.

Werner Mölders saw himself as the successor to Oswald Boelcke, the Great War ace generally acclaimed as the ‘father of air fighting’. Galland, on the other hand, regarded himself as the Richthofen of the Second World War. Both were concerned to improve their tactics. The Bf 109 was at a disadvantage in the dogfight against the better-turning Spitfires and Hurricanes. They came up with the only possible solution, which was to fight in the vertical, using initial altitude advantage to plummet down, fire, then, using their accumulated speed, climb away again. But often the situation did not allow this: Galland twice found Spitfires on his tail which he was unable to shake off. His unorthodox ploy on both occasions was to fire his guns into the blue. Seeing gunsmoke coming back, and perhaps showered with spent cases, his pursuers, possibly thinking that they had encountered a fighter with rearward-firing guns, broke off the chase.

By early September it had become increasingly obvious that Fighter Command had not been defeated in the air, nor were its aircraft being destroyed on the ground in significant numbers. If airfield attacks had not worked, a new target was needed. London! Surely the British would throw in every last fighter to defend the capital. Many fighter units from

Luftflotte 3

were redeployed to the Pas-de-Calais to give a massive numerical advantage.

In the mid-afternoon of 7 September, a massive armada of 350 bombers, escorted by more than 600 fighters, set course for the metropolis. Caught out of position by this change of targets, the defenders offered little resistance. The huge raid steamrollered its way through and inflicted massive damage on the Dockland area. German losses were a mere ten bombers and 22 fighters; RAF losses were 29.

London was again the target on 11 September, then came a relative lull for three days. Fighter Command had performed unimpressively since early September. For some while the German parrot cry had been that the British were ‘down to their last 50 Spitfires’. Now it really seemed possible.

Sunday 15 September saw a resumption of the offensive. About 150 Bf 109s drawn from several

Gruppen

set course for the capital In their midst was the bait—a mere 25 Dorniers drawn from

I

and

III/KG 76.

Fighter Command scrambled 23 squadrons, and the wished-for fighter battle began. The first encounters took place near Maidstone and continued all the way to the outskirts of London. The

Jagdflieger

tried hard to protect their charges but, in spite of their best efforts, were peeled away and run short of fuel, leaving the bombers defenceless. Fighter combat often operates on a law of diminishing returns. The more aircraft in the dogfight, the lower the percentage that become casualties. And so it proved on this occasion in which honours were even—nine 109s lost against the same number of British fighters. Two Hurricanes fell to bombers, one in a collision, but the latter paid a terrible price: six of the 25 were shot down and two more damaged beyond repair.

Launched in the early afternoon, the second raid followed the track of the first. The ‘bait’ was larger—some 114 bombers drawn from four different

Kampfgeschwader

, protected by 361 fighters! As before, the British fighters reacted in force and a running battle commenced which lasted from the coast to London itself.

The fighting was fast and confused: with so many aircraft around, it was unwise to concentrate on one for more than a few seconds for this rendered the attacker vulnerable to surprise in his turn. Surprise was, and still is, the dominant factor in air fighting, whereas manoeuvre combat rarely produces decisive results. Adolf Galland, at the head of

JG 26

on this day, later recalled his 33rd victory:

After an unsuccessful dogfight with about eight Hurricanes, during which much altitude was lost, with the Staff flight I attacked two Hurricanes about 800m below us. Maintaining surprise, I closed on the wingman and opened fire from 120m as he was in a gentle turn to the left. The enemy plane reeled as my rounds struck the nose from below, and pieces fell from the left wing and fuselage. The left side of the fuselage burst into flame.

It was fairly typical that dogfights against well-trained and mounted opponents were fruitless, even for a ‘honcho’ like Galland. Surprise attacks were far more likely to be effective, and it is significant that, even though Galland started out with a considerable altitude advantage, he ended attacking from the blind area below (

Fig. 11

). Finally, the range was fairly short at 120m: too often pilots opened fire at 300m or more and failed to connect. Galland himself often closed to what he described as ‘ramming distance’.

The running battle continued all the way to the target and back to the coast, where 50 Bf 109s, the ‘reception committee’, met the returning raiders. And still fresh British squadrons arrived to do battle! The afternoon action cost them fifteen fighters, while

Luftwaffe

losses amounted to 21 bombers and at least twelve fighters, possibly more.

September 15 was a bad day for the

Jagdflieger,

It showed clearly that they were nowhere near gaining ascendancy over the British fighters. In fact the enemy seemed stronger than ever, notwithstanding the weeks and months of heavy fighting. The invasion was postponed indefinitely. The night Blitz took on increasing importance, and after heavy losses in major raids on London on 27 and 30 September the daylight assault on the capital was quietly terminated.

The experimental

EprGr 210

had used Bf 109s and 110s as fighter-bombers from July, with a fair degree of success. Encouraged by this,

Reichsmarschall

Goering ordered in early September that up to one-third of all fighters must be equipped for the

Jagdbomber (Jabo)

role. Twenty-one Bf 109Es of

II/LG 2

had taken a minor part in raiding London on 15 September.

Flying high and fast, the

Jabos

were difficult to intercept, but their pilots were for the most part resentful of being relegated to the role of bomb truck. Not as well trained as the specialists of

EprGr 210

, they achieved little. Other daylight activity, such as fighter sweeps, continued, albeit at a much reduced pace. As autumn progressed, poor weather not only restricted flying: it turned the temporary landing grounds of the

Jagdflieger

to mud. As 1940 drew to a close, it became obvious to all of them that they had suffered a defeat, although the full implications of this would not be apparent for some considerable time.