Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (5 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

The early 1930s were a watershed in aircraft design and engineering, and the few years between the advent of the Polish fighters and their German adversaries resulted in a tremendous difference in performance and capabilities. The Messerschmitt Bf 109 variants used against Poland were the C, D and E models. The Bf 109D-1 was powered by the Daimler-Benz DB 600 liquid-cooled engine rated at 960hp, which gave the aircraft a maximum speed of 323mph and a higher ceiling and a greater rate of climb than previous models. Armament remained at four MG 17 machine guns; attempts to mount an MG FF 20mm cannon firing through the propeller hub were unsuccessful. Only a few Ds were produced: these were allocated to certain

Zerstörer

heavy fighter

Gruppen

as a stopgap until sufficient Bf 110s became available to equip them.

The D was followed by the E subtype, which became the first major mass-production machine. This was powered by the DB 601, which featured variable-speed supercharging, had fuel injection instead of a carburettor and was rated at 1,100hp. This gave greatly improved performance—a maximum speed of 354mph at 12,300ft, an initial climb rate of 3,100ft/min and a service ceiling of 36,000ft. Fuel injection meant that negative-g manoeuvres could be made without the engine cutting—a tremendous advantage in combat. The two nose machine guns were retained, but the wing machine guns were replaced by 20mm MG FF cannon, to give a large increase in hitting power. Wing loading, at 321b/ sq ft, was fairly high for a single-seat fighter at that time, and turning ability was comparatively modest.

Turning ability is dependent on two factors—wing loading and speed. If two fighters are co-speed, the more lightly wing-loaded one will generally be able to out-turn its opponent. However, if it is travelling significantly faster than its opponent, the opposite will often apply.

Rate of climb has a rough relationship to acceleration. The fighter with the better rate of climb will generally be able to out-accelerate its opponent in level flight.

When a fighter reaches its ceiling, manoeuvrability is considerably reduced. A ceiling advantage often indicates a manoeuvre advantage throughout the higher altitude spectrum.

What does comparison of basic performance figures tell us? First, the Polish fighters would be hard put to intercept even the German bombers unless they were exceptionally well placed at the outset. Given the rudimentary system of early warning, and the lack of radios in the Polish fighters, luck would have to play a large part in achieving this. Secondly, the low wing loadings of the P.7s and P.11s would allow them to turn more tightly than their adversaries, speed for speed, but their otherwise poor performance would not allow them to force battle on the

Jagdflieger,

nor would it allow them to disengage unless the German pilots were willing, for whatever reason, to break off the action.

The third

Luftwaffe

fighter type to see action in Poland was the Messerschmitt Bf 110. Designed as a long-range escort fighter, it first flew in May 1936, a year later than the 109. Although this aircraft was far less manoeuvrable than, and had an acceleration inferior to, its single-engine sibling, trials in 1937 showed it to be appreciably faster than the Bf 109B which was currently in production. This, plus the perceived need for a long-range fighter to escort bombers deep into enemy territory, ensured its eventual adoption by the

Luftwaffe.

The Bf 110B-1 was powered by two DB 600A liquid-cooled inline engines and was very heavily armed, with a battery of two 20mm MG FF cannon plus four 7.9mm MG 17 machine guns in the nose. The need for long-range radio communications resulted in a second crew member being carried; in combat he provided a rearward lookout and gave a modicum of rearward protection with a swivelling 7.9mm MG 15 machine gun.

With the advent of the superior DB 601 engine, production of the B-1 was halted in favour of the C-1, which was powered by this unit. Other changes embodied extensive structural strengthening, and a slightly reduced wingspan. The maximum speed of the C-1 was 336mph at 19,686ft; initial climb rate was 2,165ft/min, service ceiling 32,810ft and wing loading at maximum all-up weight a moderate 331b/sq ft.

The

first Jagdflieger action

of the war occurred on 1 September, when P.11 cs and P.7s of the Pursuit Brigade encountered Heinkel bombers heading for their airfield at Okecie. The escorting Bf 110s of

I(Z)/LG 1

were slow to react but eventually accounted for two P.7s, although their

Kommandeur,

seven-victory Spanish Civil War veteran Walter Grabmann, was wounded in the action. This was hardly a promising combat début for the

Zerstörer.

That afternoon

I(Z)/LG 1

was again in action, this time while escorting bombers over Warsaw itself. Led in Grabmann’s absence by

Hauptmann

Schlief, they tangled once more with the Pursuit Brigade. The initial bounce from above failed, but then the Germans tried the decoy trick, one of the oldest in the book (

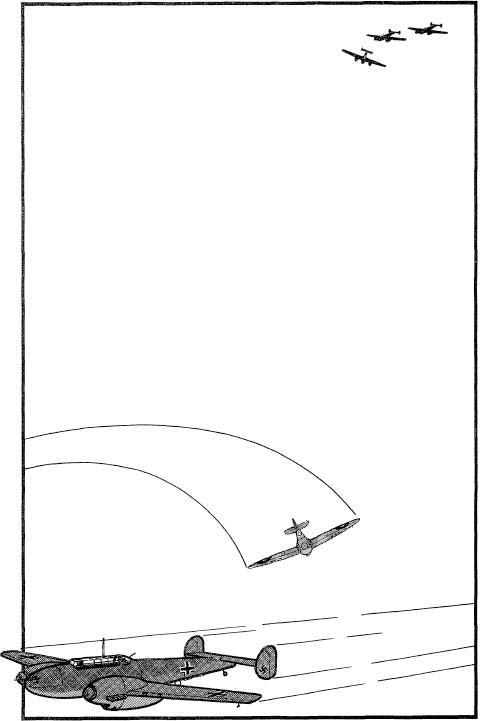

Fig. 7

). A single 110 slipped away on its own, flying slowly and uncertainly. A P.11 pounced on it, only to fall to the lurking Schleif’s guns. Four more Polish flyers were decoyed and shot down in this way before the action was broken off.

The correct tactics against the lightly wing-loaded Polish fighters were dive and zoom, or high-speed slashing attacks, but often the temptation to start turning with them proved too much. This was not a good idea. On the afternoon of 2 September about twenty Bf 110s

of I/ZG 2

clashed with six P.11s, two of which were shot down, one by future night fighter

Experte

Helmut Lent, but at a cost of three of their own. While the Polish fighters might be technically outclassed it was yet another matter to underestimate the skill of the man in the cockpit, and an error of the first magnitude to fight on his terms.

In a matter of days the air battle for Poland had been decisively won by the

Luftwaffe.

Most of the escort missions were carried out by the Bf 110

Gruppen:

the shorter-legged Bf 109s were mainly employed on defensive duties. This apart, the German top scorer of the Polish campaign was Hannes Gentzen,

Kommandeur

of the Bf 109D-equipped

I

/

ZG

2, with seven victories, consisting of two fighters and five bombers. No other German fighter pilot attained five victories.

The Polish campaign was notable for the number of future

Experten

who scored their first victories there. Among these were Bf 110 pilots Wolfgang Falcke of

I

/ZG

76

, with three victories, and Gordon Gollob, later to become the first man to score 150 victories, of the same unit. Bf 109 pilots who later became famous were Hans Phillipp of

I/JG 76

, Erwin Clausen and Fritz Geisshardt of

I(J)/LG 2

and Gustav Rödel of

I/JG 21.

Great Britain and France declared war on Germany shortly after the invasion of Poland had begun, and a British Expeditionary Force was deployed to France. This included an air component with bomber and army co-operation squadrons, and four fighter squadrons of Hurricanes. Little action could be undertaken by the Allied ground forces, but interception of reconnaissance aircraft of both sides over France and Germany, and clashes in the air along the border, became fairly frequent events.

Fig.

7.

The Decoy

The decoy, a solitary aircraft looking vulnerable in the presence of enemy fighters while covered by friends above, was widely used until late 1943. Large numbers of high-performance enemy fighters made it a suicidal manoeuvre after this time.

The basic tactical unit of

l’ Armée de l’ Air

was the

Groupe de Chasse,

which consisted of two or three

Escadrilles

of about twelve fighters each. This was roughly equivalent to the

Luftwaffe Gruppe

and its constituent

Staffeln,

although the French unit had no counterpart to the German

Stab.

In turn, two or three

Groupes

combined to form an

Escadre de Chasse,

which, although similar to a

Geschwader

in composition, differed from it in being tied to a fixed base. Redeployment from one base to another thus involved a change of designation for the unit concerned. Abbreviations were commonly used: for example,

GC II/5

was the second

Groupe de Chasse

of the fifth

Escadre.

Tactically,

l

’ Armée de l’ Air

had continued where it had left off in 1918. The basic fighter element was the three-aircraft

patrouille

in Vic formation, spaced at about 600ft laterally and 160ft vertically with the low man on the sun side. The standard attack was from the beam, which in theory ended in a difficult full-deflection shot but more often resulted in a curve of pursuit to bring the fighter on to its opponent’s tail. Early warning was by lookout, linked by the unreliable French telephone system. It was backed by a form of radio-location which, using alternate transmitters and receivers, could produce an approximate location for an aircraft, albeit with no indication of height, out to about 31 miles, but was unsatisfactory against a formation.

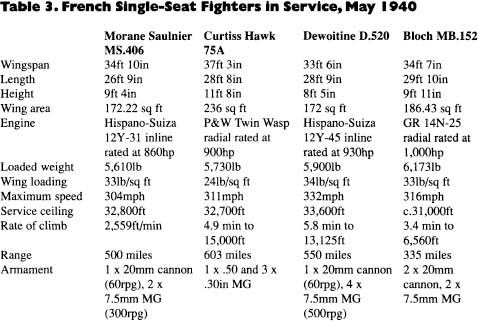

On the outbreak of war, the two main French fighter types were the Morane Saulnier MS.406 and the American-built Curtiss Hawk 75. First flown (as the MS.405) in August 1935, the former was powered by a Hispano-Suiza liquid-cooled engine rated at 860hp and armed with two wing-mounted 7.5mm machine guns and an engine-mounted 20mm cannon. Maximum speed was 304mph at 16,405ft and initial climb rate 2,559ft/min. Wing loading at 331b/sq ft made it a fairly agile aircraft. Although generally outperformed by the Bf 109E, if well handled it was a worthy opponent. Rather better was the Hawk 75. It was of comparable performance to the MS.406, but with a superior rate of climb and significant handling advantages, and its Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp radial engine was less vulnerable to battle damage. Two-thirds of all

confirmed

Armée de l’ Air

victories up to 25 May 1940 were scored by Hawk 75 pilots.

The first fighter engagement over France came on 8 September when a

Schwarm

of Bf 109Es of

I/JG 53

clashed with five Hawks of

GC II/4.

Spanish

Experte

Werner Mölders was one of the victims, forced to land with a shot-up engine, although it was not long before he restored the balance. A more significant combat took place on 6 November 1939. Polish campaign top-scorer Hannes Gentzen, at the head of

JGr 102 (I/ZG 2

was still equipped with Bf 109s), was patrolling the frontier between the Maginot and Siegfried Lines. Well below he spotted a French Potez 637 on reconnaissance, escorted by nine Hawk 75s of

GC III5.

Everything was in his favour—altitude, combat experience, and a numerical advantage of 3:1. He dived to the attack.

The French fought back fiercely. During the ensuing dogfight four Bf 109s were shot down and another four force-landed. The sole French casualty was a Hawk 75 which belly-landed but was repairable. A German fighter unit had attacked with every advantage in its favour, yet had been thoroughly trounced. How could this happen?

There were three main reasons. First, the alertness of the French pilots prevented

JGr 102

from achieving surprise. Secondly, the Hawk 75 was in some ways far superior to the Bf 109D. Although performance was slightly inferior, it was far more manoeuvrable, thanks to a lower wing loading combined with finely harmonised controls, which gave a smaller turning radius coupled with a much faster rate of roll which allowed it to establish itself in a turn faster than the German fighter could manage. An automatic constant-speed propeller enabled the 1,200hp Twin Wasp to run at maximum efficiency throughout the speed range, unlike the manually adjusted propeller of the Messerschmitt, which in combat was more of a distraction than an asset.