Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (23 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

I was well positioned at the correct altitude of 3,300m… and directed on to the enemy by means of continual corrections. Suddenly I saw an aircraft in the moonlight, about 100m above and to the left; on moving closer I made it out to be a Vickers Wellington. Slowly I closed in from behind, and aimed a burst of 5–6 seconds’ duration at the fuselage and wing root. The right motor caught fire immediately, and I pulled my machine up. For a while the Englishman flew on, losing height rapidly. The fire died away but then I saw him spin towards the ground, and burst into flames on crashing.

Becker had been lucky. In bright moonlight he had closed to a range of about 50 metres before opening fire without being spotted. It would not always be so easy. Two hours later

Unteroffizier

Fick of the same unit was guided to another Wellington, only to open fire at too long a range. Thus warned, the bomber escaped.

Becker also carried out the first German interception using airborne radar. On the night of 9/10 August 1941 he eased his Dornier Do 215 off the runway at Leeuwarden and climbed to his patrol position. Soon the controller directed him towards a contact. After a certain amount of jockeying for position, radar operator Josef Staub obtained a contact about 6,500ft away and carefully steered his pilot towards it. Twice evasive action by the bomber broke the radar contact, which was only regained by a hard turn in the direction that the target had vanished. Finally Becker and Staub closed to visual range and opened fire. Between 12 August and 30 September Becker claimed a further five bombers.

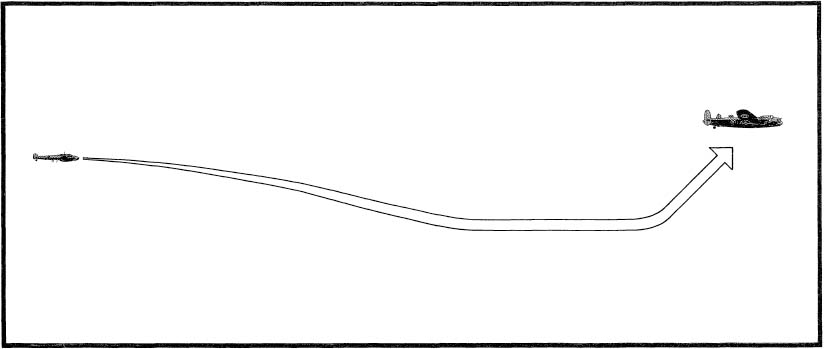

Fig. 19. Ludwig Becker’s Night Stalk

Directed by ground radar, Becker closes in on the bomber, slightly lower to silhouette it against the sky. He than gains speed in a shallow dive to bring him within range quickly. Having levelled off and matched his speed to that of the bomber, he eases up into position, then pulls his nose up and opens fire.

During this time Becker developed a specific method of attack which he passed on to other

Nachtjagdflieger.

On gaining radar contact, he closed on his quarry from a slightly lower altitude until he gained visual contact. In this way his fighter was masked against the dark ground below, while the bomber was limned against the lighter sky. Provided nose-to-tail separation distance at visual contact range permitted, he then pushed his nose down and accelerated in a slight dive to close the horizontal separation quickly. This reduced the chance of being spotted by the enemy rear gunner. Having attained a suitable position behind and below, Becker then levelled off and decelerated to match his speed to that of the bomber. Easing up until he was barely 150 feet lower, he then pulled the nose up, on which his fighter mushed and lost speed, and, as he fired, the bomber was raked from nose to tail by a hail of shells. See

Fig. 19

.

Effective though this method was, it was not foolproof. On very dark nights visual contact could only be gained at ranges too close to use the ‘up and under’ approach. In this case, all that could be done was to come in from astern and hope that the British rear gunner was not ready and waiting. But even the ‘up and under’ method had its problems. It demanded a very high level of piloting skill to get into exactly the right attack position, and few

Nachtjagdflieger

were good enough to do it consistently—and even if they were, it was a hazardous procedure. If the bomb load was hit and detonated, the night fighter stood little chance of surviving the ensuing explosion. On the other hand, if the bomber suffered catastrophic damage from the first burst, the attacker was hard pressed to stand from under as it fell from the sky. Many

Nachtjagdflieger

died when they collided with their stricken victim.

Ludwig Becker, not to be confused with the later

Experte

Martin Becker (58 victories from September 1943), was needlessly lost in daylight, intercepting a formation of USAAF heavy bombers over the North Sea on 26 February 1943. With him went Staub, who had shared in 40 of his 46 night victories.

| 7. THE YANK HE COMETH, 1943–45 |

From quite early in the war, RAF Bomber Command had found that daylight raids by unescorted bomber formations generally resulted in prohibitive casualties. Consequently, with one or two notable exceptions, deep penetration raids on German targets were made at night. The inherent inaccuracy of night bombing limited its effectiveness and was wasteful of resources, but, as it was the only means available of hindering German industrial output, these drawbacks were accepted.

By contrast, the USAAF pinned its faith on precision bombing, which could only be carried out in daylight. The American theory was that the cross-fire from massed formations of heavily armed bombers would provide an effective defence against fighter attack. Their main heavy bomber type was the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, later variants of which carried up to ten 0.50in machine guns, which packed a heavy weight of fire and were effective out to a range of over 2,000 feet.

The first American heavy bomber units arrived in England in 1942 determined to demonstrate that daylight bombing was a viable proposition. For all that, they were initially cautious, and the first targets selected were in Occupied France. The onus of finding the best method of tackling the four-engine giants thus fell upon the two resident units,

JG 2

and

JG 26

.

The great size of the B-17 (it had a wing span of nearly 104ft) caused problems in judging distance, both horizontally and vertically. On 9 October 1942 Josef ‘Pips’ Priller led

III/

JG 26

against a bomber formation. Three times he misjudged the aircraft’s height and had to back off and climb once more until at last he pulled up level with them. Once there, he led his unit into a standard attack from astern, but his pilots had the greatest difficulty assessing range. Otto Stammberger of the same unit recalled the difficulties:

We attacked the enemy bombers in pairs, going in with great bravado: closing in fast from behind with throttles wide open, then letting fly. But at first the attacks were all broken off much too early—as those great ‘barns’ grew larger and larger our people were afraid of colliding with them. I wondered why I had scored no hits but then I considered the size of the things: 40 metres span! [A slight exaggeration.—Author.] The next time I went in I thought: get in much closer, keep going, keep going. Then I opened up, starting with his motors on the port wing. By the third such firing run the two port engines were burning well, and I had shot the starboard outer motor to smithereens. The enemy ‘kite’ went down in wide spiralling left-hand turns, and crashed just east of Vendeville; four or five of the crew baled out.

Stammberger was shot down by a Spitfire on 13 May 1943, his score at seven, all heavy bombers. He was quoted as saying, ‘I simply couldn’t handle the Spitfires. It might be that I wasn’t cut out for turning around, but I am built more for boring straight in!’ His injuries were so severe that he never returned to a fighter cockpit.

Further south, the great naval bases on the Brittany coast frequently received the attentions of the Fortresses. Air defence in this area was the responsibility of

JG 2 ‘R

ichthofen’

. As many were to find later, the conventional attack from astern was hazardous. Overtaking from behind was a lengthy process during which the attackers were assailed by literally hundreds of heavy machine guns. While the standard of gunnery in the USAAF was not high, the sheer volume of fire was such that many fighters were hit even before they had come within effective firing range.

Egon Mayer,

Kommandeur

of

III/JG

2, in conjunction with

Staffelkapitän

Georg-Peter Eder, sought a better method—one that would reduce the risks to the

Jagdflieger

but still allow them to bring down heavy bombers. Examination of shot-down aircraft showed that the weakest area of defensive fire was the front. Early models of the B-17 carried a single rifle-calibre machine gun in the nose, but this was rightly regarded as little more than a ‘scare’ weapon. Therefore, Mayer and Eder concluded, the best solution was to attack from head-on (

Fig. 20

). This had added advantages. First, the high closing speed of a head-on attack reduced the time that the German fighters were under fire to a matter of a few seconds. Secondly, a head-on attack made the control cabin the main target. With no frontal armour or other protection, this was very vulnerable, and hits in this area were likely to bring success.

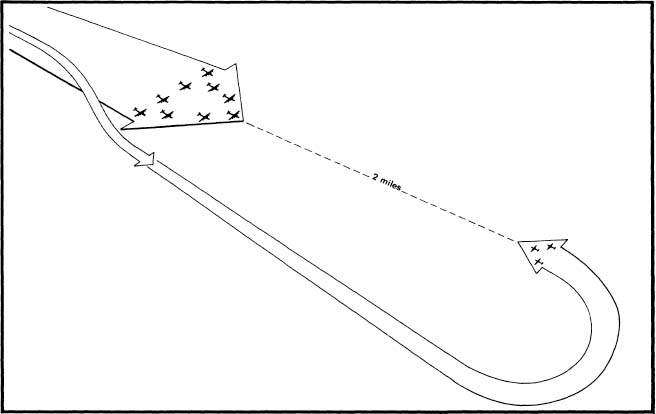

Fig. 20. Against the ‘Heavies’

Egon Mayer and Georg-Peter Eder of JG 2 developed this method of attacking American heavy bomber formations. Having tailed them to establish exact course

,

altitude and speed

,

they then moved out to a safe distance on one flank and overtook them. Having gained a lead of about two miles

,

the German fighters turned in for a head-on pass

.

The head-on attack was tried for the first time on 23 November, when the Fortresses raided St Nazaire. Another innovation tried at this time, although not retained for long, was for the fighters to fly in

Ketten

of three aircraft to match the American Vics. It was a success: four bombers went down and others were badly damaged.

Mayer and Eder now began to refine their tactics. To be effective, the attack had to be made from exactly head-on. Even a few degrees’ difference gave apparent movement to the target, making accurate shooting more difficult and increasing the risk of collision. When the Fortresses were still tiny dots in the distance, it was difficult to judge whether the attack was truly head-on or not; and by the time it became apparent that it was not, it was too late to do anything about it.

To eliminate this,

III/JG 2

met the bombers well forward, and followed them for a short while to determine their exact course and altitude. They then pulled off to one side and accelerated past out of range to a position about two miles ahead. Once there, the fighters turned through 180 degrees, lined up and ran in to attack. The closing speed of about 700 feet per second meant that the firing pass was very brief: less than two seconds elapsed between reaching maximum effective firing range and having to break to avoid a collision.

Seen through the Revi gunsight, the B-17s at first looked like tiny dots with thin wings as each German pilot selected a victim. The wings slowly grew lumps, which turned into engines. Finally the entire bomber grew, first filling the sight, then spreading across the entire windshield at nightmarish speed (

Fig. 21

). Only the stoutest could hold on until the last split second before hauling clear. Even then the order of the day was ‘gently does it’. Too hard a pull on the stick caused the fighter to mush off speed, making it an easier target for the air gunners. The technique was to go just over, making sure there was enough clearance to miss the huge fin, or just under. Once past, the fighters kept going flat out until clear of the defensive fire zone before pulling up to reposition.