Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (19 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

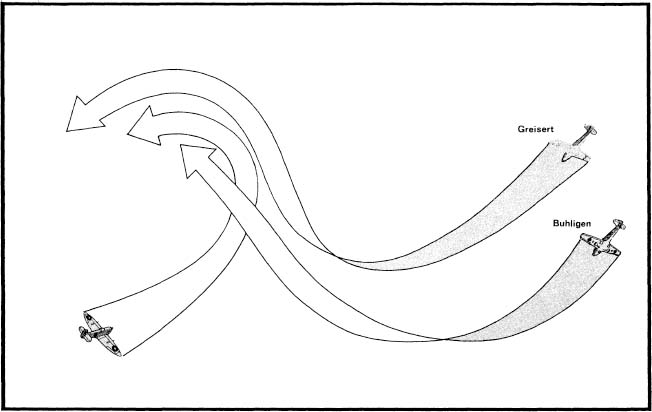

Fig. 16. Bühligen’s Victory, 13 June 1941

Bühligen’s leader, Heinrich Greisert, attacks a Spitfire, misses and overshoots. Passing above, he commences a hard turn to port. The Spitfire pilot tries to turn inside Greisert

,

only to find Bühligen on his tail. Despite his excess speed, Bühligen manages to pull lead and open fire, scoring hits. This is a typical dogfight victory, lasting mere seconds from start to finish.

There are several points of interest in this account. The leader did not even attempt to attack the bombers, which, given the strength of the escort, would have been very hazardous. The opening attack consisted of a fast dive to below the Spitfires, followed by a pull-up into the blind spot astern and underneath. It appears that the recommended method of breaking off an attack was downwards, keeping in the blind spot, rather than pulling up and over, although had Greisert pulled up more steeply he would not have ended with the Spitfire on his tail. Finally, Bühligen managed to turn briefly with his second victim. While the Spitfire could, speed for speed, handily out-turn the Bf 109F, the fact that the latter was positioned astern allowed it to keep its sights on for a brief space of time without turning so tightly, and to shoot across the circle, albeit at a rapidly increasing deflection angle. Only when a maximum-rate turn had been established for a few seconds would the Spitfire’s superior turning ability have become decisive. See

Fig. 16

.

Shortly afterwards Bühligen pulled off a successful bounce against a Hurricane, again coming up and under, for his third victim of the sortie. His score now climbed rapidly, reaching 21 on 4 September 1941. A trick from his personal bag was to have his aircraft trimmed tail-heavy. While it needed a slight forward pressure on the stick to hold it in level flight, it responded better to a backward pull, pitching up rapidly without mushing.

Having converted to the FW 190A,

II/JG 2

was transferred to Tunisia in November 1942 where, in the face of overwhelming numbers, Bühligen scored 40 victories in five months. Returning to the West in 1943, he reached the century mark in June 1944, by which time he had risen to

Kommodore

and had established a reputation as a slayer of heavy bombers. He was shot down only three times in over 700 missions,

and his final total of 112 Western-flown victims was exceeded by only two other pilots.

WALTER OESAU

‘Guile’ Oesau was one of the great

Jagdwaffe

leaders of the war. He combined fighting ability, leadership and the ability to impart his methods to others with great mental and physical stamina. Johannes Steinhoff, who we will meet in a later chapter, called him the toughest fighter pilot in the

Luftwaffe

—high praise indeed from the man who rose to command the post-war German Air Force.

Starting the war with eight victories in Spain, Oesau continued scoring in France and the Battle of Britain. As

Kommandeur

of

III

/

JG 51

from August 1940, he attained his twentieth victory of the war on the 18th of that month, the fifth pilot to do so. On 5 February 1941 he became the fourth pilot to reach 40.

Transferred

to III/JG 3

as

Kommandeur

for ‘Barbarossa’, he accounted for 44 Russians in five weeks before being recalled to the West to replace Balthasar as

Kommodore

of

JG 2

in July, and he became the third German pilot to reach 100 victories (after Mölders and Lützow) on 26 October. As previously noted, many Eastern Front

Experten

failed to make the transition.

Back in the West, Oesau’s scoring rate slowed, but this did not prevent him from becoming the third

Experte

to reach the century mark, on 26 October 1941. But further victories were now few and far between, and he was given a staff post in June 1943. In October of that year he returned to combat at the head of

JG 1

, tackling the huge fleets of American bombers and sending down at least ten of these aircraft. On 5 May 1944 his luck ran out and he was shot down and killed by USAAF Lightnings over the Eiffel. His final score was 123, amassed in just over 300 sorties.

ADOLF GALLAND

Galland is considered by many to have been the greatest

Experte

of all. His final total of 104 was not exceptional by

Jagdwaffe

standards, even though all were gained against the Western Allies, the vast majority of them before November 1941. He was one of the great characters of the

Luftwaffe.

By nature a showman, he liked the good things of life, including the company of glamorous women, and

flew the only Bf 109F to have a cigar lighter installed. Painted beneath the cockpit was his personal insigne, a cigar-smoking Mickey Mouse brandishing a revolver and a hatchet. His view of the fighter war was:

Their element is to attack, to track, to hunt, and to destroy the enemy. Only in this way can the eager and skilful fighter pilot display his ability. Tie him to a narrow and confined task, rob him of his initiative, and you take away from him the best and most valuable qualities he possesses: aggressive spirit, joy of action, and the passion of the hunter.

At the start of the year his score stood at 58. For months opportunities were few, and only nine more had been added by mid-June, three of them on 15 April when, with typical Galland bravura, he and his

Kacmarek

made an unscheduled detour to the English coast with a crate of champagne and a basket of lobsters stowed in the fuselage.

On 21 June Galland led his

Stab

and a

Staffel

of

JG 26

to intercept a Circus near Arques:

From a greater height I dived right through the fighter escort on to the main bomber force. I attacked the lower plane of the lower rear row from very close. The Blenheim caught fire immediately. Part of the crew baled out.

In the meantime my unit was struggling with Spitfires and Hurricanes. My wingman and I were the only Germans attacking the bombers at that moment. Immediately I started my second attack. Again I managed to dive through the fighters. This time it was a Blenheim in the leading row of the formation. Flames and black smoke poured from her starboard engine.

It is what is not said in this account that makes it interesting. Not only was the first attack made without hindrance from the escorts, but Galland was apparently able to distance himself from the mêlée sufficiently to gain enough altitude for a repeat performance. Certainly four minutes elapsed between attacks, and this is a long time in air combat. It seems probable that, after his first attack, Galland broke away in a shallow high-speed dive to gain separation before pulling back up to reposition. By this time he had lost the factor of surprise and the Spitfires were waiting. Although his second attack was successful, his Bf 109 was so badly shot up that he was forced to belly-land. Hegenauer, his wingman, was badly hit and baled out. As if this were not enough excitement for one day, Galland took off alone (Hegenauer had not yet returned) that afternoon against another Circus and picked off a Spitfire with a surprise bounce. This was his 70th victory. But moments later he was hit

from behind by another Spitfire and his aircraft set on fire. Slightly wounded, he barely succeeded in baling out of his stricken fighter.

Ordinarily a devotee of the fast plunging attack from an altitude advantage, Galland could be more subtle on occasion. When cloud cover was suitable, it was not unknown for him to ease his way into a Circus as though he had every right to be there. In a sky filled with aircraft, four Messerchmitts were easily mistaken for friendlies, especially if they were making no overtly hostile moves. On 13 November 1941 Galland flew with Peter Goering, the

Reichsmarschall’s

nephew, against

… a formation of Blenheim bombers which were heavily protected by fighters. On our climb we passed near this hellish ‘goods train’. We were overtaking British fighters right and left. This was so incredibly impertinent that it succeeded.

This apparently innocuous approach was the air combat equivalent of sauntering with hands in pockets and whistling! Even climbing, the two 109s were able to overtake because the escorts were throttled back and weaving to stay with the bombers. But on this occasion it all went badly wrong. As he opened fire Peter Goering was shot down and killed by the Blenheim’s turret gunner.

Between June and November 1941, when he was taken off operations, Adolf Galland increased his tally by 27, bringing his total to 94. As

General der Jagdflieger

he made occasional operational sorties to see the situation for himself, and in January 1945, when he was relieved of his command, he formed the jet fighter unit

JV 44,

with which he added to his total.

| 5. NORTH AFRICA |

Initially neutral, Italy joined the war on the side of Germany in June 1940 but in the final month of that year suffered a spectacular reverse in Libya at the hands of the British. From the German viewpoint, her ally was strategically vital inasmuch as the Italian Fleet and Air Force could, in theory, deny the British passage through the Mediterranean. If the Italians were unceremoniously bundled out of North Africa, this would no longer be the case. In this event, there could be no guarantee that Italy would not make a separate peace, or, even worse, change sides (as, indeed, was to happen later). The Germans’ presence in North Africa was at first little more than a move to keep their southern partner in the war. From there the logical next step was to conquer Egypt, thus sealing the Mediterranean at its eastern end while opening the way to the Middle East oilfields. But as Axis ambitions increased, so did their logistics problems. This inevitably highlighted Malta.

Malta was a small island some sixty miles from the southern coast of Sicily. The home of British air and naval bases, it was ideally situated to interdict Axis sea and air supply routes to Libya, while at the same time giving local air support to British naval units in transit between Gibraltar and Alexandria. It soon became obvious that success in North Africa was largely dependent on eliminating Malta as a British base.

The North African theatre divides into three dissimilar campaigns. The first two, operations against Malta and the fighting in the Libyan/ Egyptian desert, ran in parallel from 1941 to 1943. The third arose from the massive Allied landings in French North Africa late in 1942 and continued until the final collapse of Axis resistance a few months later.

One factor was consistent throughout 1941 and 1942. The best British fighters were retained for home defence. Malta and the Desert Air Force had to make do with second-rate equipment. In the early days this consisted of Gloster Gladiator biplanes and war-weary Hurricane Is. Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks and Kittyhawks were introduced from June 1941 and April 1942 respectively. Considered inadequate for the fighter role in Europe, they were sent to the desert, where they were a match for most Italian fighters of the period, although considerably inferior to the German Bf 109E and F. The same can be said of the Hurricane IIC, which, despite its more powerful Merlin engine and exceptionally heavy armament of four 20mm Hispano cannon, lacked the performance to match the German fighters. Not until March 1942 did the first Spitfire Vs arrive, first in Malta then shortly afterwards in the desert squadrons. But by this time the even more potent Bf 109G was starting to equip the

Jagdgruppen.