Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (22 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

Intruder operations began in August 1940. A German airborne radar was still far in the future, although the Dorniers were fitted with an infra-red searchlight. As the range of this device was a mere 650 feet, it was as good as useless. Consequently the German night fighters were reliant on visual contact. Over England this was not as hopeless as it was in the cloud-laden skies of Germany. Airfield flarepaths would act as a magnet for them; returning bomber crews would be tired and off-guard, and on many occasions they burned their navigation lights as a guard against collision with friendly aircraft.

The first sorties were largely a test of the British defences, but the

Nachtjagdflieger

soon gained confidence enough to prowl across East Anglia, the Midlands and northern England. Eighteen victory claims were submitted during the remainder of 1940, although RAF records appear to indicate that some of these were a trifle optimistic. The price was high. One aircraft was shot down and another damaged by British night fighters, one fell to ground defences, six were lost in crashes (some of them on training flights) and four simply went missing. Yet others sustained varying degrees of damage.

Things improved in 1941, when a total of 123 claims was made by mid-October, for losses of 28. Radar-equipped British night fighters

accounted for seven of these, while another two are believed to have been ‘own goals’, shot down by ‘friendly’ intruders. Two collided with their targets, one was downed by return fire from a bomber, ten crashed for various reasons,and six went missing without trace.

One of the more successful intruder pilots was Heinz Sommer, who was credited with ten victories in the role. In the small hours of 30 April 1941 he was patrolling over East Anglia when

I saw an English aircraft fire recognition signals and flew towards it where I found an airfield, illuminated and very active. I joined the airfield’s circuit at between 200 and 300 metres [altitude] at 00.15 hours and after several circuits an aircraft came within range. I closed to between 100 and 150 metres and fired. After a short burst the aircraft exploded in the air and fell to the ground. At 00.20 hours I saw another aircraft landing with its lights on which I attacked from behind and above at roughly 80 metres. The aircraft crashed after my burst of fire and caught fire on hitting the ground. In the light of the flames from the two wrecks, I could see fifteen to twenty aircraft parked on the airfield. I dropped my bombs on these …

Sommer went on to attain a final score of 19 before his death in action on 11 February 1944. Victories were not always this easy: intruders in the vicinity were usually the signal for all lights to be switched off, while the radar-equipped Beaufighters of the RAF made life increasingly hazardous. Nor, it must be admitted, did intruder activity ever reach the stage where it reduced the level of intensity of British raids on Germany. British records show that, during 1941, 86 aircraft were known to have been attacked by intruders (many others were lost to unknown causes). Of these, slightly less than half were bombers from operational squadrons, two-fifths were trainers and the rest were fighters. Given this proportion, it would have been strange indeed if RAF bombing had been affected.

A few pilots were outstandingly successful in the intruder role. When in November 1941 operations ceased, Wilhelm Beier had accounted for 14 aircraft and Hans Hahn and Alfons Köster 11 each. Beier’s speciality was following returning bombers over the North Sea, and all his combats took place near the English coast. Two fighters, a Hurricane and a Defiant, were among his victims. He survived the war with a total of 36 victories. Hahn was killed on 11 October 1941 when he collided with his twelfth and final victim. Köster died when he crashed in fog on 7 January 1945, having accounted for 29 aircraft. Of the others, Heinz Strüning was shot down by an RAF night fighter on Christmas Eve 1944, his score 56, and Paul Semrau fell to Spitfires at Twente on 8 February 1945 with 46 victories to his credit.

It was always apparent that the night fighter needed outside assistance if it was to find its prey, and that radar, allied to close ground control, was the only feasible method. Speed being of the essence, the

Luftwaffe

used what was readily available. The result was three separate radars to cover a single small area, one for early warning, a second to track the bomber and a third to track the night fighter. The latter had to be guided to within visual distance of the bomber within seven minutes, the time it took for the bomber to cross the radar zone. This was not too bad on a moonlit night with good visibility, but in poor conditions visual distance was reduced to perhaps 200 feet, making the task close to impossible. There were, however, a few fighter pilots who consistently beat the odds, among them Werner Streib and Ludwig Becker.

The next step was airborne interception radar, the first successful interception with which took place on 9/10 August 1941. It was obviously far easier to direct the fighter to within radar range of its target, perhaps two to three miles, than to the 200-300 metres needed for visual contact. Once in radar contact, the fighter could close to visual distance unaided.

The end of 1941 saw the night

Experten

building up respectable scores. In the lead with 22 was Werner Streib, closely followed by Paul Gildner with 21 and Helmut Lent with 20. In the main their victories had been gained solely with the aid of ground control, aided by the fact that in the summer months the German night sky is always fairly light to the north. An approach from the south of a bomber therefore gave a good chance of a visual sighting.

At this time the British bombers flew singly, with each crew responsible for its own courses and timings. This was the threat that the German night defence system had to counter. The number of radar-controlled night fighter zones was increased, while in February 1942 the first production airborne radar sets reached the operational units. Like their RAF counterparts, the German night fighter crews at first had little time for temperamental ‘black boxes’, but, encouraged by Becker’s successes of the previous year, they persevered. Gradually bomber losses rose.

In warfare nothing is ever certain. Just when it appeared that the

Nachtjagdflieger

had taken the measure of their opponent, a change of British tactics reversed the situation. Instead of dozens of bombers operating individually, they were concentrated in time and space. On the night of 30 May 1942 the first ‘Thousand Bomber Raid’ was launched against Cologne. Penetrating on a narrow front, the bombers swamped the few radar zones that they crossed. Only about 25 night fighters could be brought into action, leaving dozens of others sitting helplessly on

the ground with no targets. Bomber losses fell. The obvious counter to the bomber stream was a much looser form of fighter control which could feed fighters into it, there to hunt autonomously with their own radars. But this was not done for some time; instead, the defensive zones were deepened and two fighters rather than one were used in each.

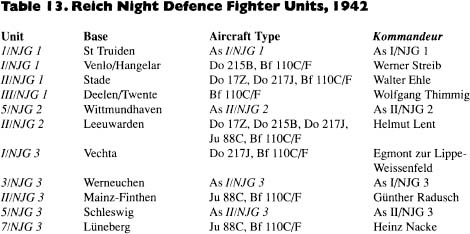

By autumn that year all night fighters were equipped with radar. Bomber losses once more started to rise. Among the

Nachtjagdflieger,

Helmut Lent now led the field with 49, outstripping Reinhold Knacke and Ludwig Becker with 40 each. Knacke, a rising star of

I/NJG 1

, had set a record on 16/17 September 1942 with five victories in one night. Paul Gildner of

II/NJG 1

and Prince Egmont zur Lippe-Weissenfeld of

5/NJG 2

were equal fourth with 38 apiece.

At the start of the night offensive against Germany, the RAF deployed three main types of twin-engine bomber, the Hampden, the Whitley and the Wellington. The first two were phased out during 1942 in favour of the new breed of four-engine bombers, the Stirling and the Halifax in the first half of 1941 and the Lancaster in March 1942. All except the Hampden were heavily armed against attack from the rear by a powered gun turret fitted with four 0.303in calibre Brownings, while the four-engine types also featured a twin-gun dorsal turret. While the hitting power of the Browning was not very great, it still made a stern attack hazardous for the

Nachtjagdflieger.

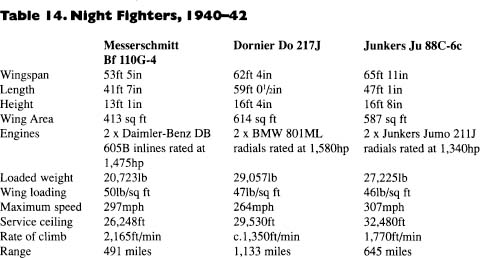

As noted, the main

Luftwaffe

night fighter of this period was the Bf 110. The first variant produced specifically for night fighting was the F-4, which had a position for a third crew member to work the radar and was powered by two DB 601E engines rated at l,300hp. The main night fighter variant was the Bf 110G, which was introduced late in 1942. It was armed with two 20mm MG 151 cannon and four MG 17 machine guns, plus a swivelling gun in the rear cockpit. Despite greater available power, increasing weight allied to the drag of the bristling radar aerials reduced performance considerably. The Junkers Ju 88 started life as a high-speed bomber but, as related, was quickly adapted for the night role. It was not as docile and was less manoeuvrable than the Bf 110, but its performance made it well suited to night fighting.

The Dornier Do 17Z-10 was quickly replaced by the more potent Do 215B-5, but only a few of these were produced. The final Dornier variant was the Do 217J, which entered service in the early summer of 1942, but this was overweight and its performance was poor. It was phased out in 1943.

Experten

The demands of night fighting were very different from those of the day battle. Patience and perseverance were the keynotes, allied to superior blind flying and navigational skills. In the early years, the weather was the main enemy. Ice and fog accounted for more night fighters than the RAF gunners, while frustration at the lack of results was undoubtedly a cause of many accidents.

Successful night interceptions were primarily the result of teamwork. Skilful ground control could position a fighter very close to a bomber on the darkest night, but only if the pilot displayed equal skill in following instructions. With the advent of airborne radar, it became a matter of teamwork between the pilot and his operator. The ability of the latter to interpret where the bomber was—and, even more important, what it was doing—from small blips of light on two or even three cathode ray tubes was vital. Mutual trust was essential. The radars of the day had a rather long minimum range, and often contact was lost before a visual sighting became possible. The pilot then had to keep closing, in the full knowledge that the target was somewhere close ahead, and the slightest misjudgment could result in a mid-air collision. Successful night fighting demanded not only a first class pilot, but a first class radar operator also.

HELMUT LENT

Like many other

Nacht jagdflieger

, Helmut Lent commenced the war as a

Zerstörer

pilot. Flying with

I/ZG 76,

he shot down a Polish fighter on the second day of the war, two British Wellingtons over the German Bight in December 1939 and a Norwegian Gladiator over Oslo-Fornebu in April 1940. With a score of eight victories by day, he was posted as

Staffelkapitän

of

6/NJG 1

in January 1941.

By April several of his pilots had scored, but Lent had flown two dozen fruitless sorties. Disturbed by his failure to find the bombers at

night, he requested a transfer back to day fighters. He was persuaded to give it another try, and on his 35th sortie on 12/13 May he accounted for two Wellingtons. Having discovered the secret, his score mounted swiftly. On 8 January 1943 he accounted for a Halifax, to become the first

Nachtjagdflieger

to reach 50. On 20/21 April 1943 he was the first night flyer to shoot down a Mosquito, and he topped the 100 mark by destroying three Lancasters on 15/16 June 1944. It was not without cost: he was wounded on three occasions. Helmut Lent was killed in a landing accident at Paderborn on 5 October 1944, his total score 110, of which 102 were at night.

LUDWIG BECKER

A pioneer night fighter with

II/NJG 1

, Becker contributed a great deal to

Nachtjagdflieger

tactics in the early days. He it was who scored the first ground-assisted night victory on 16 October 1940. Flying a Dornier Do 17Z-10, he reported: