Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (24 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

Once proven, the head-on attack was adopted by the entire

Jagdwaffe

as the best means of tackling the American ‘heavies’. On average it took twenty hits with 20mm shells to bring down a heavy bomber. Given the average standard of

Jagdflieger

marksmanship, this was rarely achieved in a single burst, even though the German fighters, Bf 109s and FW 190s, were later up-gunned. More often, bombers were damaged in the first pass and forced out of formation. Once away from the combined defensive fire of the box, stragglers could be hacked down relatively easily.

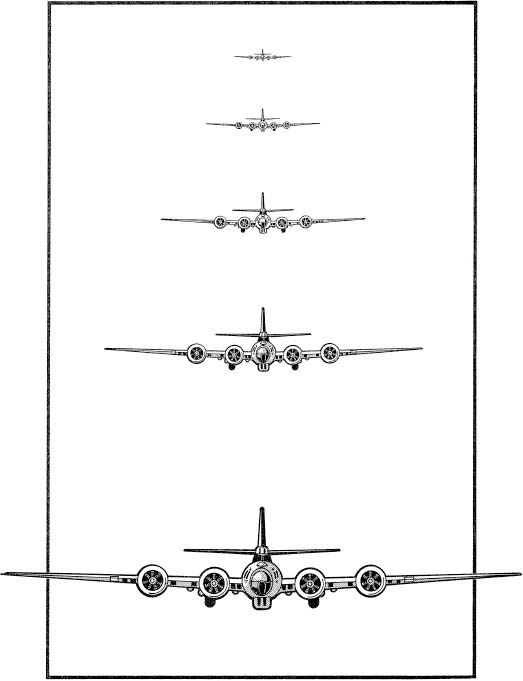

Fig. 21. Head-on Against the ‘Heavies’

Combined closing speeds made attacking heavy bombers from head-on a frightening experience. From top to bottom: Range two miles

,

time to collision 15 seconds; range one mile

,

time to collision seven seconds; range 3

,

000ft

,

time to collision four seconds; range 1

,

800ft

,

time to collision 2

.

5 seconds

,

open fire; range 750ft

,

time to collision one second

,

stop firing and

break

!

Air combat against enemy fighters was widely regarded as an exciting if lethal sport, in which the best pilot won. Attacking the massed daylight bomber formations was a different matter entirely. Shooting apart, there was little opportunity for the exercise of traditional combat skills. In fact, it had much in common with infantry going ‘over the top’. The attacker was under fire all the way, and survival was very much a matter of chance. A fighter pilot could do everything by the book and still get shot down, for no other reason than an American gunner happened to fire in the right direction at the right time. Carrying out what amounted to a cavalry charge on the bombers was a supreme test of nerve. Hans Philipp became

Kommodore

of

JG 1

on April 1943, after a very successful spell in the East. He described it thus:

To fight against twenty Russians that want to have a bite of one, or also against Spitfires, is a joy. And one doesn’t know that life is not certain. But the curve into seventy Fortresses lets all the sins of one’s life pass before one’s eyes. And when one has convinced oneself, it is still more painful to force to it every pilot in the wing, down to the last young newcomer.

On 8 October 1943, Hans Philipp, victor of 206 combats, 177 of which were in Russia, was shot down and killed by Thunderbolt escort fighters near Nordhorn.

Emboldened by early success, the American heavy bombers penetrated German air space for the first time on 27 January 1943, with a raid on Wilhelmshaven. They were intercepted by the FW 190As of

JG 1

. Lacking the experience of the Channel coast

Geschwader

,

JG 1

attacked from astern, only to be dismayed by the amount of return fire. Only three B-17s were shot down, at the cost of seven fighters.

As American penetrations became ever deeper, Reich home defence was strengthened, and the

Jagdflieger

gradually took the measure of this new threat. Bomber losses rose, although not to the point where they became unacceptable. One thing was quickly evident, however:

the armament of the German fighters was inadequate for the task. Various expedients were tried to remedy this. Heinz Knoke,

Staffelkapitän

of the recently formed

5/JG 11

, hit on the idea of aerial bombing. A time-fuzed bomb, released about 3,000 feet above a tightly packed bomber formation, could have a lethal effect. On 22 March 1943 he tried it for the first time:

I edge forward slowly until I am over the tip of the enemy formation, which consists entirely of Fortresses. For several minutes I am under fire from below, while I take a very rough sort of aim on my target, weaving and dipping each wingtip alternately in order to see the formation below. Two or three holes appear in my left wing.

I fuze the bomb, take final aim, and press the release button on my stick. My bomb goes hurtling down. I watch it fall, and bank steeply as I break away.

Then it explodes, exactly in the centre of a row of Fortresses. A wing breaks off one of them, and two others break away in alarm.

The bombing experiment continued for a while, but with limited success. The problems of accurate aiming were simply too great. Aiming was also the Achilles’ heel of the 21cm rocket mortar, which could be launched from astern, outside the defensive fire of the bombers. Time-fuzed, to be effective it had to detonate within 90ft of a bomber. Not only did range estimation prove intractable, but low all-burnt velocity meant that the weapon needed to be aimed about 200ft above its target. While some bombers were shot down with this weapon, its main value was as a means of breaking up a bomber formation, thus rendering individual aircraft more vulnerable to conventional attack.

Laden with bombs or rocket mortars, the

Jagdflieger

were extremely vulnerable to escort fighters. As the latter became more numerous and longer-ranged, the use of these weapons was finally abandoned. At first the only Allied escort fighters available were short-legged Spitfires. Then, in April 1943, the first P-47 Thunderbolts made their appearance, closely followed by P-38 Lightnings. The Thunderbolts could barely reach the German border and the usual

Jagdwaffe

ploy was to delay until they turned for home, when a series of conventional attacks could be made. An innovation at this time was the use of shadowing aircraft. These followed the bombers at a distance and radioed back information on force composition, heading and speed. Ground control then used this to position the

Jagdgruppen

for attack.

On 17 August 1943 the USAAF launched a two-pronged attack on Regensburg and Schweinfurt with 363 heavy bombers in two waves. This was their deepest penetration yet, and it cost them dearly. The

Jagdflieger

flew more than 500 sorties, accounting for the lion’s share of the 60 bombers downed and badly damaging many others, losing 25 of their own number in the process. This was a victory for the defenders, even though both targets were bombed. Deep penetration raids were few over the next seven weeks. Then, on 14 October, the USAAF returned to Schweinfurt in strength. Once again the

Jagdwaffe

reacted with ferocity, broke up many bomber formations and inflicted heavy losses. This was the last unescorted deep penetration raid of the war.

With the aid of long-range drop tanks, Thunderbolts were able to extend their operational radius well into Germany. The Lightnings could range even farther afield, while 1944 saw the operational debut of the P-51B Mustang, which could reach Berlin. From this point on the bombers would never fly alone: escort fighters would always be on hand to protect them.

The

Jagdwaffe

was caught on the horns of a dilemma. With the failure of less conventional weapons, it had resorted to adding extra guns to many of its fighters. Heavier calibres were also used, mainly 30mm cannon. Just three hits from this weapon were usually enough to knock down a four-engine bomber, as opposed to the twenty hits needed with 20mm shells. But the extra weight and drag of these cannon, which were often mounted in underwing gondolas, reduced manoeuvrability and rendered the fighters more vulnerable in combat against American fighters.

The casualty rate was horrific: over 1,000 German fighter pilots were lost in the first four months of 1944. While the vast majority were novices, all too many were irreplaceable veterans. To name but a few, Horst-Günther von Fassong (136 victories) fell to Thunderbolts on 1 January; head-on attack pioneer Egon Mayer (102, of which 24 were heavy bombers), the first to reach 100 victories entirely in Western Europe and known to his opponents as ‘the man in the white scarf, was shot down by Thunderbolts near the Luxembourg border on 2 March; and Emil Bitsch (108) fell to Spitfires over Holland on 15 March, Wolfe-Dietrich Wilcke (162) to Mustangs on the 23rd, Josef Zwernemann (126) to Mustangs

on 8 April and Kurt Übben (110) to Thunderbolts on 27 April. Nor were the bomber gunners idle, accounting for Gerhard Loos (92) and heavy bomber

Experte

Hugo Frey (32, of which 26 were four-engine), both on 6 March. It was the shape of things to come.

Raids at this time typically consisted of between six and eight hundred four-engine bombers and a similar number of escort fighters. However, for technical reasons the escorts had to operate in relays. In practice this meant that only a fraction of the escort fighter force was on station at any one time, to protect a bomber stream several miles wide and between 70 and 100 miles long. Consequently the American fighters could not be everywhere, let alone in strength.

General der Jagdflieger

Adolf Galland sought to exploit this potential weakness. Whilst the head-on attack gave a reasonable kill-to-loss ratio, it was obvious that far better results could be achieved by the traditional attack from astern, if only this could be done without incurring unacceptable losses. His solution was the

Gefechtsverband

—a large mixed fighter battle formation. The heart of this was the

Sturmgruppe

, which flew the FW 190A-8/R8

‘Sturmbock

’ (Battering Ram). This carried two 30mm MK 108 cannon in the outboard wing positions, two 20mm MG 151s in the wing roots and two 12.7mm machine guns in the engine cowling, giving it a very heavy punch. For protection, extra armour was fitted to the engine, cockpit and gun magazines, with bulletproof glass panels scabbed on to the quarterlights and canopy sides. The other two

Gruppen

, the function of which was to hold off the escort fighters, flew the Bf 109G-10, which was optimised for air combat.

In action the

Sturmgruppe

flew in

Staffeln

, each in arrowhead formation. They closed from astern to a range of 300ft or less, braving the defensive fire. Walther Hagenah of

IV(Sturm)/JG 3

later recalled:

During the advance each man picked a bomber and closed on it. As our formation moved forwards the American bombers would, of course, let fly at us with everything they had. I can remember the sky being almost alive with tracer. With strict orders to hold our fire until the leader gave the order, we could only grit our teeth and press on ahead. In fact, however, with the extra armour, surprisingly few of our aircraft were knocked down by the bombers’ return fire: like the armoured knights of the Middle Ages, we were well protected. A

Staffel

might lose one or two aircraft during the advance, but the rest continued relentlessly on.

Meanwhile the function of the two

Begleitengruppen

was to ward off the Allied escorts and allow the

Sturmgruppe

to do its work without let or hindrance. But on the occasions when they failed, the slow and unmanoeuvrable

Sturmböcke

were, despite their added protection, easy prey for Allied fighters.

The greatest difficulty was getting the

Gefechtsverband

into position. Containing between 90 and 100 aircraft, it was unwieldy to manoeuvre. Operating under close ground control, with enough warning to allow the component units to take off, form up and reach altitude, there was no real problem in clear skies. But clear skies were, as we have already noted, rare in Northern Europe, and maintaining formation integrity while climbing through cloud was nigh on impossible. The other imponderable was the American fighter force. Unlike the

Jagdflieger

in the Battle of Britain, it was not shackled to the bombers, but was free to range out in front and on the flanks of the bomber stream. Once discovered, a

Gefechtsverband

acted as a Mustang magnet, drawing in the escorts from far and wide. Walter Hagenah later recalled that he got into position behind an American bomber on only four occasions in the summer of 1944. While he claimed an American bomber on each, this was a poor return for the effort expended.

The fact was that, by the middle of 1944, the

Jagdwaffe

had lost control of the skies over the Fatherland. Outnumbered and technically matched, they fought for their very lives on four fronts—the East, the West, the Italian and the Reich. Shortage of fuel curtailed flying training; bomber pilots were remustered to the

Jagdwaffe

, where their previous training proved a handicap. The ‘old heads’ daily grew fewer in number and the replacement pilots were barely worthy of the name. The year 1944 was critical for the

Jagdwaffe:

it never recovered its former supremacy.

With the Third Reich fighting for its very life, it is easy to portray the German fighter pilots as merciless automata. This was far from the case, as many examples quoted later prove. One incident from this period took place on 20 December 1943. A B-17 of the 379th Bombardment Group flown by Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Brown was badly damaged

by flak and fighters over Bremen. With the plexiglass nose shattered, one engine out and two others damaged, Brown recovered control at low level and set course for England. He was intercepted by Bf 109 pilot Franz Stiegler of

6/JG 27

, a North African veteran with 27 victories, who in 1992 recalled: