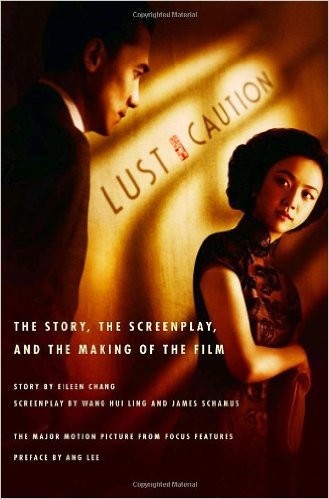

Lust, Caution

Authors: Eileen Chang

Eileen Chang

LUST, CAUTION

Eileen Chang (Zhang Ailing) was born in Shanghai, China, in 1920. She studied literature at the University of Hong Kong but in 1941, during the Japanese occupation, she returned to Shanghai, where she published

Romances

(1944) and

Written on Water

(1945), which established her reputation as a literary star. She moved to Hong Kong in 1952 and in 1955 to the United States, where she continued to write. She died in Los Angeles in 1995.

ALSO BY EILEEN CHANG

Love in a Fallen City

The Rouge of the North

Written on Water

Contents

FOREWORD

Julia Lovell

“To be famous,” the twenty-four-year-old Eileen Chang

wrote, with disarmingly frank impatience in 1944, “I must hurry. If it comes too late, it will not bring me so much happiness. . . . Hurry, hurry, or it will be too late, too late!” She did not have long to wait. By 1945, less than two years after her fiction debut in a Shanghai magazine, a frenzy of creativity (one novel, six novellas, and eight short stories) and commercial success had established Chang as the star chronicler of 1940s Shanghai: of its brashly modern, Westernized landscapes populated by men and women still clinging ambivalently to much older, Chinese habits of thought. “The people of Shanghai,” she considered, “have been distilled out of Chinese tradition by the pressures of modern life; they are a deformed mix of old and new. Though the result may not be healthy, there is a curious wisdom to it.”

Chang’s own album of childhood memories was a casebook in conflict between the forces of tradition and modernity, from which she would draw extensively in her writing. The grandson of the nineteenth-century statesman Li Hung-chang—a high-ranking servant of China’s last dynasty, the Ch’ing—her father was almost a cliché of decadent, late-imperial aristocracy: an opium-smoking, concubine-keeping, violently unpredictable patriarch who, when Eileen was eighteen, beat and imprisoned his daughter for six months after an alleged slight to her stepmother. Her mother, meanwhile, was very much the kind of Westernized “New Woman” that waves of cultural reform, since the start of the twentieth century, had been steadily bringing into existence: educated and independent enough to leave her husband and two children behind for several years while she traveled Europe—skiing in the Swiss Alps on bound feet. After Chang’s parents (unsurprisingly) divorced when she was ten, the young Eileen grew up steeped in the strange, contradictory glamour of pre-Communist Shanghai: between the airy brightness of her mother’s modern apartment and the languid, opium smoke–filled rooms of her father’s house.

Yet while Chang’s fiction was eagerly devoured by the Shanghai readers for whom she wrote— the first edition of her 1944 collection of short stories sold out within four days—it drew carping criticism from literary contemporaries. For Eileen Chang wrote some way outside the intellectual mainstream of the middle decades of twentieth-century China. Although an early-twenty-first-century Western reader might not immediately notice it from much of her 1940s fiction—the body of work for which she is principally celebrated—she grew up and wrote in a period of intense political upheaval. In 1911, nine years before she was born, the Ch’ing dynasty was toppled by a revolutionary republican government. Within five years, this fledgling democracy collapsed into warlordism, and the 1920s through ’40s were marked by increasingly violent struggles to control and reform China, culminating in the bloody Sino-Japanese War and civil conflict between the right-wing Nationalists and the Chinese Communist Party. Many prominent Chinese writers of these decades—Lu Hsün, Mao Tun, Ting Ling, and others—responded to this political uncertainty by turning radically leftward, hoping to rouse the country out of its state of crisis by bending their creative talents to ideologically prescribed ends.

Despite experiencing firsthand the national cataclysms of the 1940s—the Japanese assault on Hong Kong and occupation of north and east China (including her native Shanghai)—Eileen Chang, by contrast, remained largely apolitical through these years. Although her disengaged stance was in part dictated by Japanese censorship in Shanghai, it was also infused with an innate skepticism of the often overblown revolutionary rhetoric that many of her fellow writers had adopted. In the fiction of her prolific twenties, war is no more than an incidental backdrop, helping to create exceptional situations and circumstances in which bittersweet affairs of the heart are played out. The bombardment of Hong Kong, in her novella

Love in a Fallen City

, serves only to push a cynical courting couple to finally commit to each other. In the short story “Sealed Off,” two Shanghai strangers—a discontented married man and a lonely single woman—are drawn into conversation in the dreamlike lull that results while the

Japanese police perform a random search on the tram in which they are traveling.

Defying critics who scorned her preoccupation with “love and marriage . . . leftovers from the old dynasty and petty bourgeois” and her failure to write in rousing messages of “youth, passion, fantasy, hope,” Chang instead argued for the subtler aesthetics of the commonplace. Writing of “trivial things between men and women,” of the thoughts and feelings of ordinary, imperfect people struggling through the day-to-day dislocations caused by war and modernization, she contended, offered a more acutely realistic portrait of the era’s desolate transience than did patriotic demagoguery. “Though my characters are not heroes,” she observed, “they are the ones who bear the burden of our age. . . . Although they are weak—these average people who lack the force of heroes—they sum up this age of ours better than any hero. . . . I don’t like stark conflicts between good and evil . . . we should perhaps move beyond the notion that literary works should have ‘main themes.’” Eileen Chang was one of the relatively few writers of her period who adhered to the belief, throughout her career, that the business of the fiction writer lay in sketching out plausibly complex, conflicted individuals—their confusions, frustrations, disappointments, and selfishness— rather than in attempting uplifting political advocacy. “This thing called reality,” she meditated in a deadpan account of the bombing of Hong Kong, “is unsystematic, like seven or eight phonographs playing at the same time, each its own tune, forming a chaotic whole. . . . Neatly formulated visions of creation, whether political or philosophical, are bound to irritate.”

Chang’s lack of interest in politics and inevitable antipathy toward the strident aesthetics of socialist realism efficiently guaranteed her exclusion from the Maoist literary canon and impelled her to leave China itself. In 1952, three years after the Communist takeover, as the political pressures on her grew, she decided to abandon her beloved Shanghai, first for Hong Kong and then for the United States, where she lived and continued to write until her death in 1995. In the post-Mao literary thaw, even as Mainland publishers and readers delightedly rediscovered Chang’s sophisticated tales of pre-1949 Shanghai and Hong Kong, critics were still unable to rid themselves of long-standing prejudice against her, belittling her work for its neglect of the “big issues” of twentieth-century China: Nation, Revolution, Progress, and so on.

Begun in the early 1950s, finally published in 1979, “Lust, Caution” in many ways reads like a long-considered riposte to the needling criticisms by the Mainland Chinese literary establishment that Chang endured throughout her career, to those who dismissed her as a banal boudoir realist. For while the story carries all the signature touches that marked Chang as a major talent in her early twenties—its attentiveness to the sights and sounds of 1940s Shanghai (clothes, interiors, streetscapes); its cattily omniscient narrator; its deluded, ruthless cast of characters—it adds an intriguingly new element to this familiar mix. In it, Chang created for the first time a heroine directly swept up in the radical, patriotic politics of the 1940s, charting her exploitation in the name of nationalism and her impulsive abandonment of the cause for an illusory love. “Lust, Caution” is one of Chang’s most explicit, unsettling articulations of her views on the relationship between tidy political abstraction and irrational emotional reality—on the ultimate ascendancy of the latter over the former. Chia-chih’s final, self-destructive change of heart, and Mr. Yee’s repayment of her gesture, give the story its arresting originality, transforming a polished espionage narrative into a disturbing meditation on psychological fragility, self-deception, and amoral sexual possession.

For until its last few pages, “Lust, Caution” functions happily enough as a tautly plotted, intensely atmospheric spy story. A handful of lines into its opening, Chang has intimated, with all the hard-boiled economy of the thriller writer, the harsh menace of the Yees’ world: the glare of the lamp, the shadows around the mahjong table, the flash of diamond rings, the clacking of the tiles. Brief exchanges establish characters and relationships: the grasping Yee Tai-tai, the carping Ma Tai-tai, the obsequious black capes, the discreetly sinister Mr. Yee. Chia-chih’s entanglement with her host is exposed with the slightest motion of a chin, her coconspirators introduced through a brief, cryptic telephone conversation, the plot’s two-year backstory outlined in a few paragraphs. At times, the reader struggles to keep up with the speed of Chang’s exposition, as characters and entanglements are mentioned then left swiftly behind: the disappointing K’uang Yu-min; the seedy Liang Jun-sheng; the bland Lai Hsiu-chin, Chia-chih’s only other female coconspirator; the shadowy Chungking operative Wu.

The suspense reels us steadily along, through the wait in the café, the stage-managed visit to the jewelry store and the ascent to the office, and into the story’s startling finale—the section to which Chang is said to have returned most often over almost three decades of rewriting. Chang draws us artfully into her heroine’s delusion, enveloping Chia-chih’s progression toward her error of judgment in the sweet, stupefying air of the dingy jeweler’s office. Afterward we follow Chia-chih on her sleepwalk out of the store, sharing her surreal confidence that she will be able to escape quietly for a few days to her relative’s house, until we wake at the shrill whistle of the blockade and the abrupt braking of the pedicab. Mr. Yee’s return to the mahjong table brusquely exposes the true scale of Chia-chih’s miscalculation: his ruthless, remorseless response, his warped sense of triumph. “Now that he had enjoyed the love of a beautiful woman, he could die happy—without regret. He could feel her shadow forever near him, comforting him.

Even though she had hated him at the end, she had at least felt something. And now he possessed her utterly, primitively—as a hunter does his quarry, a tiger his kill. Alive, her body belonged to him; dead, she was his ghost.”

This final free indirect meditation echoes with Chang’s ghostly, sardonic laugher—mocking not only her weak, self-deceived heroine, but also her own gullible attachment to an emotionally unprincipled political animal. For Chang’s obsessive reworking of Chia-chih’s romantic misjudgment was, at least in part, autobiographically motivated. Like Chia-chih, Eileen Chang was a student in Hong Kong when the city fell to the Japanese in 1942, and she, too, subsequently made her way to occupied Shanghai. Also like Chia-chih, shortly after her return to Shanghai, she entered into a liaison with a member of the Wang Ching-wei government—with a philandering literatus by the name of Hu Lan-cheng, who served as Wang’s Chief of Judiciary. In 1945, a year after the two of them entered into a common-law marriage, the Japanese surrender and collapse of the collaborationist regime forced Hu to go into hiding in the nearby city of Hangzhou. Two years later, having supported him financially through his exile, Chang painfully broke off relations with him on discovering his adultery.

Far beyond its specific autobiographical resonances, though, the story’s skeptical disavowal of all transcendent values—patriotism, love, trust—more broadly expresses Chang’s fascinatingly ambivalent view of human psychology: of the deluded generosity and egotism indigenous to affairs of the heart. In “Lust, Caution,” the loud, public questions—war, revolution, national survival—that Chang had for decades been accused of sidelining are freely given center stage, then exposed as transient, alienating, and finally subordinate to the quiet, private themes of emotional loyalty, vanity, and betrayal.