Making a Point (3 page)

Authors: David Crystal

A sacred text has a hugely privileged position within a society. Great care needs to be taken to protect its identity, to ensure that it is transmitted accurately from generation to generation. At the same time, all sacred texts need to be interpreted and edited, so that their meaning will come across clearly and effectively to readers. The intervention takes a variety of forms. The impulse to make the work beautiful leads to decoration, with sometimes whole pages devoted to a single word or letter, as in the magnificently illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels. The impulse to teach leads to the addition of notes and commentary. And the impulse to clarify leads to the highlighting of individual words, names, or sentences, the marking of chapters and verses â and the insertion of punctuation marks.

Augustine argues that punctuation has a critical role to play in enabling readers to arrive at a correct interpretation of scripture, and he proposes two rules of thumb. The first and most important rule is to allow what we know about the world (the world of Christian faith, in his case) to influence our decision about where to place a punctuation mark. The second is to carefully examine the context in which a particular sentence is used, as this can clarify its meaning and

suggest how a punctuation mark might help. But he is aware that these principles don't solve all problems of ambiguity in writing. He concludes:

Where, however, the ambiguity cannot be cleared up, either by the rule of faith or by the context, there is nothing to hinder us to point the sentence according to any method we choose of those that suggest themselves.

Any method we choose. This personal decision-making lies at the very heart of punctuation, and becomes a recurrent theme over the next 1600 years.

3

To point, or not to point?

Word-spacing is an important first step in making a text easier to read, but it doesn't take us very far, once sentences become long and complex, and a written discourse starts to grow. Readers then need help. But the earliest texts from antiquity gave precious little guidance about how they were to be read.

Manuscripts did usually show the major divisions of a work, such as chapters or paragraphs. The beginning of a new section might be identified by a large (sometimes coloured or decorated) letter, or by indenting the first line, or by outdenting it â having it start in the left-hand margin. A mark in the shape of an ivy-leaf (or

hedera

) might indicate the beginning of a piece of commentary, distinguishing it from the preceding main text. Quite a lot of use was made of a special > mark in the margin to mark a quotation or a paragraph opening â it was called a

diple

, from the Greek word for âdouble', referring to the two lines in the character. Apart from marks showing these major structural locations, blocks of writing were unpunctuated. There might be the occasional pause shown within a paragraph. Nothing more.

Punctuation, in short, was as much the job of the reader as the writer. An impulse to punctuate comes when readers encounter a piece of writing that is ambiguous or unclear, or where the provided punctuation is insufficient for their needs. If the writers haven't done enough, then readers feel they have to do something about it. Old manuscripts often

show readers adding marks to a text to help their understanding. Sometimes readers have disagreed about what to do, and we see marks crossed out or replaced.

It's no different today. Even with the highly punctuated texts of modern print, we often find ourselves needing to add extra marks. People look at a text they need to speak aloud, such as a lecture, speech, or script, and mark places to pause, or underline words they want to emphasize. Actors might add arrows to show the voice rising and falling, or other features resembling musical notation. Newsreaders mark places where they need to be careful of a particular pronunciation, such as not adding an

r

in the phrase

law and order

. When people have to engage seriously with a text, as when studying or preparing for a business meeting, they underline, put marks in the margin, or highlight passages in bright colours to identify the bits they think are important.

Over the centuries, writers gradually came to realize that, if they wanted their meaning to come across clearly, they couldn't leave the task to their readers. And this was aided by the change in reading habits I referred to in the previous chapter. It's difficult to see how punctuation could have developed in a graphic world where

scriptura continua

was the norm. If there are no word-spaces, there's no room to insert marks. Writers or readers might be able to insert the occasional dot or simple stroke, to show where the sense changed, but it would be impossible to develop a sophisticated system that would keep pace with the complex narratives and reflections being expressed in such domains as poetry, chronicles, and sermons. However, once word-spaces became the norm, new punctuational possibilities were available.

It nonetheless took a while for a punctuation system to develop in England. The first missionaries, copying word-spaced manuscripts in their monastery scriptoria, evidently

didn't feel the need for it. Their Latin was good, they knew the texts well, and their focus was on spiritual practices, so they didn't need the extra help that punctuation might provide. In any case, many authors thought it was the job of readers to discover the meaning of scripture for themselves, not for writers to âdictate' how it should be interpreted by adding marks to the page. Punctuation was never going to be a priority in such a climate.

But times changed. Later generations of monks often had a poor knowledge of Latin, and became increasingly dependent on glosses into English. Literacy ability varied greatly. Bede, in a letter to Eusebius, abbot at Jarrow, in 716, complains about how he has had to edit his commentary on St John's

Apocalypse

in a certain way to take account of âindolence' in his readers. By the time of King Alfred the Great, at the end of the ninth century, the combined effect of political turmoil, Viking invasions, and general intellectual apathy had led to the virtual disappearance of sophisticated literacy. In one of his writings â the preface to the English translation of St Gregory's

Cura Pastoralis

(âPastoral Care') â Alfred contrasts the early days of Christianity in England with his own time, and bemoans the way learning has been lost:

So completely had it declined in England that there were very few people on this side of the Humber who could understand their service-books in English or translate even one written message from Latin into English, and I think there were not many beyond the Humber either. So few they were that I cannot think of even a single one south of the Thames when I came to the throne.

He resolves to do something about it, initiating a programme of translation into English, and encouraging the learning of Latin.

It's a crucial turning-point. Suddenly, longer and more varied works begin to be written down in English, and to reach more people. Different styles emerge, both within poetry and prose. In poetry, we encounter long heroic narratives such as

Beowulf

alongside spiritual reflections such as

The Dream of the Rood

â early texts surviving in late manuscripts. In prose, we find political and legal texts such as laws, charters, and wills; religious texts such as prayers, homilies, and Bible translations; scientific texts dealing with medicine, botany, and folklore; and historical texts such as town records, lists of rulers, and the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

. There is much more to read, and many more people who want to read it. We are still centuries away from a world of reference where daily engagement with multiple texts is routine, where rapid and easy reading is essential, and where there is pressure on writers to express themselves clearly and effectively â âin plain English', as it is often put. But the linguistic factors that enable us to be fluent literacy multi-taskers today can be traced back to the decisions made by writers a millennium ago. A stable orthography is one of these factors, and punctuation is the backbone of orthography.

The punctuation marks we see in Old English manuscripts vary a great deal, depending on the handwriting style used, and they are often idiosyncratic; but certain general features can be observed. There was clearly a sense that words were important units of text. They are important not only in learning one's mother-tongue (âhow many words do you know?') but in learning another language (âwhat's the word for â¦?'). In a world where two languages work together with different functions â as Latin and English did in Anglo-Saxon times â the ability to identify and process words easily and quickly is paramount. Individual words come to the fore in inscriptions, glossaries, lists of names, year-dates, and many other

contexts. And in longer texts we see word-spaces supplemented by new signs to help readers identify where a word starts or where it ends.

Sometimes simple pointing suffices, as if we were to write:

this·is·an·example·of·middle·dots

Such âinterpunct' dots varied in height, influenced by the shape of the previous letter, but were usually at mid-level. They sometimes separated phrases rather than words, and even syllables within words. Their use is sporadic, working along with word-spaces in ways that are often difficult to interpret. In one line, they might suggest a pause; in another they might not. For example, in a tenth-century manuscript translation of Bede, we find a description of a solar eclipse:

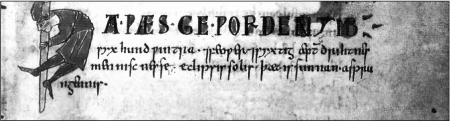

ÃA·

ÃS·GE·WORDENYMB

syx hund

yntra·

feower

syxtig æft(er) drihtnes menniscnesse· eclipsis solis·þæt is sunnan·aspru ngennis·

then was happened about

six hundred winters · and sixty-four after the lord's incarnation · (

in Latin

) eclipse of the sun · that is sun eclipse

Lines from the Old English version of Bede's

Historia Ecclesiastica

, III, Bodleian Library, Tanner MS 10, 54r. The handwriting is Anglo-Saxon minuscule

.

This extract illustrates several features of the emerging punctuation system.

- The first line is written in decorated coloured capitals, showing that it's a new section of the text; the first letter is much larger than the others, and in this text ingeniously drawn in the shape of a person climbing a pole.

- The first three words are separated by a middle dot, but so is the first syllable of

geworden

; however, there's no dot or space before the word

ymb

. - In the next line, the first phrase is separated from the rest of the line by a middle dot, with its three words spaced; we might expect the âsixty-four' to have a dot after it as well, but instead we get a wider space.

- In the third line, middle dots separate the phrases, with the constituent words spaced.

- Abbreviations are being used: there are two instances of

, the Tironian symbol for âand' â so called because it was part of a system of shorthand used in ancient Rome, supposedly invented by Tiro, a freedman of Cicero â and an example of an omitted word-ending (the

, the Tironian symbol for âand' â so called because it was part of a system of shorthand used in ancient Rome, supposedly invented by Tiro, a freedman of Cicero â and an example of an omitted word-ending (the

er

of

after

) shown by a mark over the

t

. - The scribe could not fit the Old English word for âeclipse' (

asprungennis

) into the line, so he simply continues it on the next line; there is no hyphen or other indication that a word is being split in this way. - We might expect âlord' (i.e. Jesus Christ), to have a capital letter, but there are no initial capitals used for proper names.