Making a Point (4 page)

Authors: David Crystal

This mixture of conventions is typical of manuscripts of the time.

As one reads through the manuscripts of Old English â less than a thousand in all â the differences in the use of

punctuation are striking. Apart from spaces and dots, other marks are used to show word identity. Some writers make the opening letter of a word larger; some the closing letter â an early move in the direction of capitalization, especially for proper names. If a word didn't fit at the end of a line, its incomplete state would be shown in various ways. Some scribes simply crammed the remaining syllables into the space above the line. Some shortened the word, marking the abbreviation with a stroke above the last letter. Some introduced a

J

-like mark looking like a large comma: it's called a

diastole

(pronounced die-ass-toe-lee), a convention taken over from ancient Greek. A letter might have a stroke extended to suggest a continuation: these âsuspended ligatures' were often picked up on the next line, where the first letter showed a continuation stroke. (This practice of âdouble hyphenation' lasted a long time. We'll see it again in Jane Austen, p. 100.) Gradually a special linking mark became usual, though its character varied. It might be a single horizontal mark at the end of a line (like the modern hyphen), or a double horizontal (=), or an acute accent (´), or a semi-circle below the line. The variation wouldn't be sorted out until the arrival of printing.

There are clear indications of a more sophisticated system emerging. Influenced by the practices of Irish monks, some Anglo-Saxon scribes began to use multiple marks to show pauses â the more marks, the longer the pause and the more âfinal' the intonation. Two dots, one on top of the other (like a modern colon), would show a moderate pause in the middle of a sentence. A cluster of three dots ( â often called a

â often called a

trigon

) would show a major pause at the end. An oblique line could mark a pause, as could a double oblique. In some writers it was the position of the dots in relation to the preceding letter that showed pausal distinctions: a system of two or three

dots â placed at different heights â would mark pauses of different lengths. An interesting development was a mark like an acute accent placed on top of a diastole, so that the result looked a bit like a modern semicolon.

Distinguishing between major and minor pauses is probably enough if you are reading silently and simply need some help to see where one unit of sense ends and another begins. But if you are reading aloud, you need more than this. And in the Anglo-Saxon period, reading aloud once again became a priority â at monastery meal-times, and in church.

4

No question: we need it

It's impossible to overestimate the importance of reading aloud in the liturgy of the church. In Catholic Christianity of the time, the âliturgy of the Word' ranked alongside the âliturgy of the Eucharist' â as indeed it still does. The role of the lector was vital. Passages from scripture were read aloud during Mass â and for virtually all of the congregation outside of the monastery it would be the only way in which they would ever encounter the message of the Bible, as they were unable to read it for themselves. Within the monastery, reading the daily office and listening to spiritual reading were routine. Chapter 38 of the Rule of St Benedict (written in the sixth century AD) makes this very clear:

Reading must not be wanting at the table of the brethren when they are eating. â¦

Let the deepest silence be maintained that no whispering or voice be heard except that of the reader alone. â¦

The brethren will not read or sing in order, but only those who edify the hearers.

Only good readers, note. Make a mistake, and you were in trouble, as Benedict goes on to say in Chapter 45:

If anyone whilst he reciteth a psalm, a responsory, an antiphon, or a lesson, maketh a mistake, and doth not

humble himself there before all by making satisfaction, let him undergo a greater punishment, because he would not correct by humility what he did amiss through negligence.

In such a climate, anything which would help your reading to come across well would be highly valued.

Punctuation was seen to be one of these valuable aids. The influential eighth-century monkâscholar Alcuin, working at the court of Emperor Charlemagne, and writing in Latin, says in one of his poems (No. 94) that scribes need to pay careful attention to it when copying works to be used in the liturgy:

let them put those relevant marks of punctuation in their proper order, so that the lector may neither read mistakenly, nor by chance suddenly fall silent before the holy brothers in church.

But what did âread mistakenly' mean? It was not only a matter of knowing where to breathe, pausing between sentences, or emphasizing the right words. It was everything to do with a powerful oral delivery, in which the reader would bring out the meaning of a text, proclaiming it with emotional conviction (so that it might reach the hearts and minds of the listeners) and giving it an appropriate rhythm (so that elements of it might be more easily remembered). This demanded the use of more reliable and meaningful punctuation marks.

These new marks, increasingly seen from the end of the eighth century, are often referred to by the Latin name

positurae

, âpositions'. The distinction between a middle and a final pause was made in a more systematic way, and began to be linked with the grammar of a sentence. Paleographers have developed a terminology for talking about these.

- A

punctus versus

, or âturned point', marked the end of a statement, signalling a major break and thus a

relatively long pause. It would be heard typically as a falling intonation. It looked somewhat like a modern semicolon, with its tail usually dangling below the line of writing. An example is shown on p. 12, where it ends the first line of the manuscript. Later, this would be replaced by the point (or

full stop

, or

period

) as the primary way of showing a statement end. - A

punctus elevatus

, or âelevated point', marked a place where the first part of a sentence was over, but the sentence had not come to an end. It would be heard typically as a rising intonation. It looked like an inverted semicolon, though the upper mark was often more like an elongated acute accent than a comma. An example is shown at the end of the second line of text on p. 12.

The contrast between these two kinds of punctuation can be appreciated in a modern example. Read this passage aloud:

When you arrive, get a key from the porter. When you leave, hand it in at reception.

The normal reading (regional accents do vary a bit) is to have rising tones on

arrive

and

leave

, followed by brief pauses; and to have falling tones on

porter

and

reception

, with a longer pause after

porter

. In older terms, we would have a

punctus elevatus

followed by a

punctus versus

, twice over.

The third of the

positurae

was a real breakthrough: the arrival of the question mark.

- A

punctus interrogativus

, or âinterrogative point', signalling that the sentence was a question. It looked originally like a point with a ~ (tilde)-like mark moving off to the right above it. There are several examples in the

Colloquy

of Ãlfric, dating from around 1000 AD. This is a dialogue between a teacher and his pupils, so there are lots of

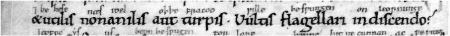

questions. The English is in the form of a gloss over the Latin words, and it is there that we see this punctuation mark, as in this line where the teacher asks: âAre you willing to be beaten while learning?' â

Uultis flagellari in discendo

A line from the opening of Ãlfric's

Colloquy

, British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius A.iii, f. 60v. The handwriting is English Caroline minuscule

.

During the Middle English period, from the twelth to the fifteenth centuries, a fourth mark was introduced:

- A

punctus admirativus

or

exclamativus

, a âpoint of admiration' or âexclamation', signalling that the sentence was to be spoken in an exclamatory way. It first appears in a few late fourteenth-century manuscripts, looking like a right-slanting colon with a longer accent mark moving off to the right above it. It would evolve into the exclamation mark of modern times.

This was also a period when there was considerable experimentation in the use of the marks inherited from Anglo-Saxon times. There was already great variation in the writing practices of the monks belonging to different religious orders and working in different monasteries. The variability became even more marked as manuscripts came to be produced outside monastery discipline. During the Middle Ages, we see notaries, clerks, commercial scribes, schoolteachers, and creative writers combining punctuation features from different systems and adding their individual preferences in an increasingly diverse range of texts.

We see new ways of marking the sections or paragraph

divisions of a text, such as the use of coloured initials or a distinctive mark â a letter C (for

capitulum

, âlittle head') with a vertical line through it, still used today (in a modified form) as ¶. Originally called a

paraph

, the term as well as the symbol evolved into what printers call the

pilcrow

(derived from

paragraph

). We see marks being used to identify a parenthesis â at first angle brackets < > and later round brackets ( ). We see frequent use of what today we call forward slashes, //, indicating a major sentence division in a paragraph, and / for a short pause within a sentence. The short pauses are sometimes shown by an upright slash, |, or by a small semi-circular mark, the ancestor of the modern comma. And we see a mark evolve to meet a new need: to show a sentence division falling between the longer and shorter divisions already captured by existing marks. We know it now as the semicolon.

At the same time as writers were developing punctuation as a guide to oratory, an important development was taking place in the universities: the emergence of the

trivium

, the âthree ways' that provided a liberal arts foundation for higher education â grammar, logic, and rhetoric. Grammar had a broader meaning than it has today, encompassing aspects of the study of literature as well as the way language uses structure to convey meaning. But the result was a focus on the way discourses in general, and sentences in particular, were constructed, and the role of punctuation as part of this process. A grammatical approach to punctuation was the result.

The medieval period thus marks the beginning of the two perspectives for punctuation that lie behind so many of the usage issues of today: should punctuation be viewed from a phonetic or a grammatical point of view? I'll explore this in detail in later chapters, but the nature of the difference can be briefly illustrated through a modern example. Take the sentence:

Of particular importance in developing a new system is the need to provide a network of supporting agencies.

When this is read aloud, most people insert a short pause after the subject of the sentence â after

system

. To do otherwise makes the sentence sound rushed, and more difficult for listeners to assimilate. An approach to punctuation that reflects the sound of speech would therefore insert a short-pause mark here â a comma. But an approach based on grammar would ask a different question: do we need to mark the end-point of the subject of the sentence? Since the eighteenth century, the answer has been âno'. The grammarians felt that the link between the subject and the rest of the sentence (the predicate) was so important that it should not be interfered with by the insertion of punctuation. And thus, anyone who wrote the following today would be considered to have made a mistake.

Of particular importance in developing a new system, is the need to provide a network of supporting agencies.

During the Middle Ages, we see increasing signs of punctuation marks being used within sentences, based on grammarians' views as to how the different parts of a sentence relate to each other. And because grammarians don't always agree about this, especially when it comes to evaluating the way meaning is distributed throughout a sentence, we see on the horizon another source of punctuational uncertainty.

The

positurae

were of great value in helping readers â especially inexperienced ones â to convey the meaning of a text accurately and effectively. They show two of the most important features of a punctuation system: the marks must be easy to see, and they must be sufficiently different from each other that there is no risk of visual confusion. But a third requirement of a punctuation system was missing: standard

use. Writers of the same language should use marks in the same way, both in the way they are formed and in the linguistic functions they convey. As literacy grew significantly during the fourteenth century, a standardized system of punctuation was desperately needed, but for this to happen a cultural shift of considerable magnitude would need to take place. It came with the arrival of printing.

Interlude: Punctuation says it all

Chapter 9

of A A Milne's

Winnie-the-Pooh

(1926) deals with an emergency âIn which Piglet is entirely surrounded by water'. âIt rained and it rained and it rained.' Piglet is marooned in his tree-home, so Pooh and Christopher Robin have to work out a way to reach him. Christopher Robin can't think of anything; but Pooh suggests a novel kind of boat.

Pooh said something so clever that Christopher Robin could only look at him with mouth open and eye staring, wondering if this was really the Bear of Very Little Brain whom he had known and loved so long.

âWe might go in your umbrella,' said Pooh.

â?'

âWe might go in your umbrella,' said Pooh.

â??'

âWe might go in your umbrella,' said Pooh.

â!!!!!!'

For suddenly Christopher Robin saw that they might.

The ancients would never have believed that, one day, such little marks would be given such semantic responsibility.