Making a Point (5 page)

Authors: David Crystal

5

The first printer

Imagine you are a printer in the Middle Ages in Europe. One of the first printers. You have manuscripts that need to be typeset. The spelling varies greatly between writers, and even within a writer. You will have to sort that. And the punctuation varies â from manuscripts that show hardly anything to those displaying a wildly idiosyncratic array of marks. You will have to sort that too. There are marks where the lines go at different angles and lengths, and groups of dots that go off in different directions. Spacing and layout is erratic, and there's a great deal of personal decoration on individual letters. Items of interest in a text are highlighted in all sorts of ways, such as by adding symbols and notes in the margins. The one comforting thing is that there seem to be far fewer punctuation marks to worry about than letters and spellings.

Although your new technology is offering all kinds of novel possibilities, and there are no precedents to guide you, you have to be realistic. Your readers are experienced readers of manuscripts. They are used to seeing handwritten punctuation marks; and despite the many idiosyncrasies among scribes, there does seem to be a fair amount of agreement in the form of certain symbols. So it will make sense to copy the scribal style as far as you can, and use marks that readers will recognize. But where there is a choice, you will need to make a decision. If a mark is sometimes written upright, and sometimes slanted to the left or right in various degrees, you

will have to choose. In some cases having a choice will be useful, as the differences will help form the visual character of different fonts of type, such as âroman' and âitalic'. In other cases, you will simply have to decide on one of the shapes and hope it will appeal.

In the case of William Caxton, who printed the first book in English, most of the typesetting decisions had already been made by earlier printers in northern Europe. He had previously been a merchant in the clothing industry in England, but moved to Bruges (in present-day Belgium), where he developed a business interest in (manuscript) bookselling. The printing industry had established itself in Germany and the Low Countries after Johannes Gutenberg's venture in Mainz around 1450. Caxton didn't get into the printing business until a decade later, by which time supplies of type were already available, manufactured by professional typecutters.

Caxton's first book,

The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye

â âa gathering together of the stories of Troy' â was printed around the end of 1473 in Bruges, in a typeface that would have been familiar to European readers. Three years later, he brought his new technology â and his printing assistants â over to England, and set up the first printing press in London in the precincts of Westminster Abbey.

The fonts of type included a few punctuation marks, and Caxton uses them â but sporadically, and not in a way that bears much relationship to present-day usage. If you read modern editions of his writing, what you will see is a repunctuated text for ease of reading, and this is some distance away from his original practice. Here's an illustration: the passage is from one of his prefaces (to a translation of Virgil's

Aeneid

). It tells a story about the way English vocabulary was developing at the time, with a northern word,

egges

, competing with a southern word,

eyren

, and thus presenting a publisher with

the problem of which word his readership will be more likely to understand.

The first version is from Norman Blake's

Caxton's Own Prose

(1973, with some glosses by me):

And that comyn [common] Englysshe that is spoken in one shyre varyeth from another. In so moche that in my dayes happened that certayn marchauntes were in a shippe in Tamyse [Thames] for to have sayled over the see into Zelande. And for lacke of wynde thei taryed atte forlond [Foreland] and wente to lande for to refreshe them. And one of theym named Sheffelde, a mercer, cam into an hows and axed [asked] for mete and specyally he axyd after eggys. And the goode wyf answerde that she coude speke no Frenshe. And the marchaunt was angry for he also coude speke no Frenshe, but wolde have hadde egges; and she understode hym not. And thenne at laste another sayd that he wolde have eyren; then the good wyf sayd that she understod hym wel. Loo! what sholde [should] a man in thyse dayes now wryte, âegges' or âeyren'? Certaynly it is harde to playse every man bycause of dyversite and chaunge of langage.

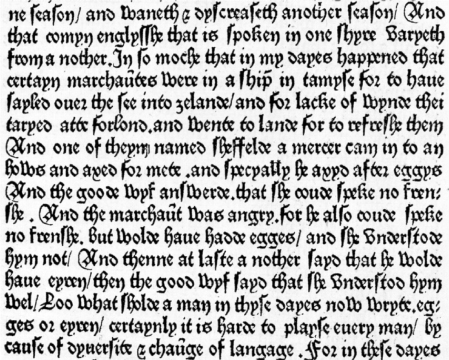

This is certainly much easier to read than the original; but it gives a completely wrong impression of Caxton's punctuation practices. What the manuscript actually shows is this:

ne season/ and waneth & dycscreaseth another season/

And

1

that comyn englysshe that is spoken in one shyre varyeth from a nother. In so moche that in my dayes happened that certayn marchaũtes were in a ship~ in tamyse for to haue sayled ouer the see into zelande/ and for lacke of wynde

thei

5

taryed atte forlond.and wente to lande for to refreshe them

And one of theym named sheffelde a mercer cam in to an hows and axed for mete .and specyally he axyd after eggys And the goode wyf answerde.that she coude speke no fren= she. And the marchaũt was angry.for he also coude speke 10 no frenshe. but wolde haue hadde egges / and she vnderstode hym not/ And thenne at laste a nother sayd that he wolde haue eyren/ then the good wyf sayd that she vnderstod hym wel/ Loo what sholde a man in thyse dayes now wryte. eg= ges or eyren/ certaynly it is harde to playse euery man/ by 15 cause of dyuersite & chaũge of langage. For in these dayes

Lines from William Caxton

, The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye

(1471), British Library, G.9723

.

The differences are fairly obvious, but it's important to look carefully at them, as they show how far removed punctuation still is from a well-developed system. It's often said that printing standardized punctuation in English. So it did, for

the most part â but only eventually (and I'll discuss the cases where it didn't succeed in a later chapter). The first books do show a regularity in the shape of the actual marks, reflecting the use of identical pieces of type; but we are a long way from stability in the way they are used.

If we look in detail at the Caxton extract, and compare it with Blake's edition, several things stand out.

- The modern version sets the story out as a separate paragraph, but Caxton makes no such division, as the opening and closing lines illustrate.

- The story is told in an informal spoken narrative style, with several uses of

and

, so that it's often difficult to decide where a sentence boundary falls. This doesn't seem to bother Caxton, who simply uses a capital letter or a pause mark (either / or .) when he feels the need to help the reader follow the sense of the passage. But he does so in an inconsistent way. This short extract illustrates all four possibilities:- in line 1, a sentence begins with a capital letter and ends with a period, as it would today

- in line 3, a sentence begins with a capital letter and has no period after

them

in line 6 - in line 15, a sentence begins without a capital letter and ends with a period

- in line 13, a sentence has neither an opening capital nor a concluding period.

The modern version uses the first practice consistently.

- in line 1, a sentence begins with a capital letter and ends with a period, as it would today

- He also uses the period to show a short pause (as in line 6), where today we would use commas (as in the modern version lines 11 and 14) or no marks at all.

- He retains the forward slash as a mark of sense division, but gives it different values:

- opening the new story in line 1

- marking minor sense breaks in lines 5 and 10, and before

by

in line 15 - marking sentence-like breaks elsewhere.

The modern version replaces all slashes by periods.

- opening the new story in line 1

- Word-spaces are mostly as today (apart from

a nother

and

in to

), but spacing is erratic in relation to punctuation marks. The extract illustrates all four possibilities:- in lines 3, 5, 11, 14, and 16, there's no space before a period and a space after, as today; a space follows the slash in all cases except in line 11, where there's a space before and after

- in line 8, there's a space before the period and none after

- in lines 6, 9, and 10, there's no space on either side of the period

- in lines 10 and 11, there's a space on either side of the period.

The modern version regularizes spaces throughout.

- in lines 3, 5, 11, 14, and 16, there's no space before a period and a space after, as today; a space follows the slash in all cases except in line 11, where there's a space before and after

- He uses a double stroke to show word division at the end of lines 9 and 14, but breaks the words in places that would not be acceptable today. The line-endings of the modern edition aren't shown above, but modern printing practice has enabled all the lines in this extract to be right-justified, so line-breaks are not needed.

There are several other points of difference. He doesn't use initial capital letters for proper names, as in lines 2 and 7. When words don't fit into the line, he uses abbreviations, as in lines 4 and 15. But the most noticeable feature of the modern version is the way it adds punctuation marks that are conspicuous by their absence in Caxton's day â the comma, exclamation mark, question mark, semicolon, and inverted commas. For these, we need to enter the sixteenth century.

6

A messy situation

We can get a sense of the relatively late development of punctuation awareness in English by looking at when the technical terms first come into the language. The word

punctuation

itself is not recorded in the

Oxford English Dictionary

until 1539.

Comma

in its sense as a punctuation mark, replacing the forward slash, is known from 1521. And during the second half of the century we encounter the first recorded uses (in their sense of marks) of

apostrophe

(1588),

colon

(1589),

full stop

(1596), and

point of interrogation

(1598 â the term

question mark

arrives surprisingly late, in 1905). The next two decades provide instances of

hyphen

(1603),

period

(1609), and

stop

(1616).

Semicolon

is much later (1644), as are the

note of exclamation

(1657), and

quotation quadrats

(1683 â what would in the nineteenth century be called

quotation marks

; a

quadrat

was a small metal block used for spacing).

Dash

and

bracket

are eighteenth century.

We should never read too much into âfirst recorded uses', of course: they tell us only the first time lexicographers have (so far) discovered that someone has written a word down. Punctuation terms would have been in spoken usage, especially among printers, for some time before they first appeared in writing. Semicolons, for instance, began to be used in English books with some frequency in the 1580s, and isolated uses can be traced back to the 1530s. They were described in several other ways before the term

semicolon

became the norm, such as

comma colon

,

hemi-colon

, and

sub-colon

. But the dates do reinforce the main observation, which is that we have to look to the end of the sixteenth century, not the fifteenth, to find a system that is similar to what we use today.

During the 1500s, we see writer after writer trying to impose order on a very messy situation. Most agree that the three main marks reflect three degrees of pause. George Puttenham, in his

Art of English Poesie

(1589), advises his readers to follow Classical models, and recognize a comma (the âshortest pause'), a colon (âtwice as much time'), and a period (a âfull pause'). So that's the formula:

one period = two colons = four commas

When the semicolon arrived, making a four-degree system, its length was usually considered to be between that of the comma and the colon. A little earlier, John Hart, in his influential

An Orthographie

(1569), uses a musical analogy. If a comma is a crotchet then a colon is a minim. Children were actually taught to count one for a comma, two for a semicolon, and so on (see my Interlude after

Chapter 10

).

The approach was frequently advocated until the nineteenth century, and is still encountered today in some recommendations for public speaking. If you try it, you'll quickly see that it's far too mechanical a system to cope with the complexities of English syntax. When followed pedantically, it produces the most bizarre and artificial rhythms. In the four-degree double-the-number system, a period is

eight

times the length of a comma!

But in Elizabethan England, many felt it was an ideal to be aimed at. It was an approach that, in the age of Shakespeare, especially appealed to actors wanting their scripts to give them as many clues as possible about how a speech should

be read. However, it didn't appeal to publishers. They were not so concerned about phonetic values. To them, it didn't matter what length the marks represented as long as they made the sense clear. The role of punctuation, in their view, was to help readers, not speakers.

This is where we see the origins of virtually all the arguments over punctuation that have continued down the centuries and which are still with us today. Should a writer use punctuation as a guide to pronunciation (a âphonetic' or âelocutional' function) or as a way of making a text easy to read (a âgrammatical' or âsemantic' function)? How should a reader interpret someone else's use of punctuation: phonetically or semantically? And how should punctuation be taught and tested in schools? Indeed,

can

it be tested in the same way as we test maths or spelling, where there are clear rights and wrongs? A punctuation mark may be correctly placed from one point of view, but incorrect from another. Tests have to be extremely sophisticated in their phrasing to ensure that tester and testee are, as they say, both on the same playing field. And the sad truth is that tests usually aren't, so that students are penalized for using punctuation one way when the tester had expected another.

But this is to leap ahead (see

Chapter 26

). In the sixteenth century there were no punctuation or spelling tests like those of today because the orthography was still developing. Several of the marks were new to English printers and readers, who were unsure how to use or interpret them. We can see this in the way the marks appear in the work of different typesetters. One of the compositors of Shakespeare's First Folio clearly liked the semicolon, as he introduces it all over the place; another prefers the colon; another has a thing for commas. Messy indeed.

It's not at all easy trying to work out how to perform a

Shakespeare play when there is such variability. Some modern directors think the plays have too much. Peter Brook, for example, has this to say (in his

Diaries

, 21 August 1975):

Shakespeare's text is always absurdly over punctuated: generations of scholars have tried to turn him into a good grammarian. Even the original printed texts are not much help â the first printers popped in some extra punctuation. When punctuation is just relaxed to the flow of the spoken word, the actor is liberated.

Others pay close attention to every little mark. When I was working with the company at Shakespeare's Globe for its 2005 production of

Troilus and Cressida

, where director Giles Block used the Folio text, there were many discussions between him and his cast over precisely how much value to attach to a comma. Here are two examples, from different plays, of the kind of issue that arises.

In

Julius Caesar

(3.1.86), Antony shakes hands with Caesar's murderers. There are no commas between the names and the pronouns â apart from after Casca:

Let each man render me his bloody hand.

First

Marcus Brutus

will I shake with you;Next

Caius Cassius

do I take your hand;Now

Decius Brutus

yours; now yours

Metellus

;Yours

Cinna

; and my valiant

Caska

, yours;Though last, not least in loue, yours good

Trebonius

.

Casca was the first to stab Caesar. Might we therefore imagine the actor playing Antony to take that comma seriously, delaying the onset of

yours

, and perhaps doing some business with Casca's hands at that point?

And here's an instance of a place where some would consider the original text to be overpunctuated, whereas others

would not. It's at the beginning of

Henry IV Part 2

(1.1.131), when Morton has come in haste to the Earl of Northumberland, bringing news of defeat at the Battle of Shrewsbury. Modern editions tend to print it like this, as with the Arden text:

The sum of all

Is that the King hath won, and hath sent out

A speedy power to encounter you, my lord â¦

But in the First Folio, we see it printed like this:

The summe of all,

Is, that the King hath wonne : and hath sent out

A speedy power, to encounter you my Lord,

Might not the commas reflect Morton's breathless state, and his nervousness in front of the Earl? Whether through accident or design, we have a text that can suggest an interesting reading or performance.

It's a complicated issue, because sometimes the printed text simply can't be trusted. Then, as now, printers made errors that weren't picked up in the proof-reading. And sometimes they ran out of type, so that they had to be inventive. The amount of type in a printer's distribution box was limited. There wasn't enough to print a whole book. Every few pages, the type that had been used to print those pages would be broken up and used again for the next few. And on occasion a printer could be caught short.

Take question marks. Printers were used to printing books of serious prose, where there's little need for question marks, so the number of pieces of question-mark type in their box would have been relatively small. But in plays, people are always asking questions â in

Hamlet

, most of all. So printers ran out, and we find them devising alternative ways of showing

a question mark, such as by inverting a semicolon or by using a comma on top of a period. In the copy of the First Folio I use, when Hamlet harangues Laertes with the line âWoo't weepe? Woo't fight? Woo't teare thy selfe?', the second and third questions end with a normal question mark, but the first has a period+comma. And in the column in which this line appears there are nine normal question marks and five abnormal ones. Nobody would notice â or, if they did, they would simply assume that these were simply alternative forms.

At times the language itself was no help. It's easy enough to punctuate a text if you can understand exactly what's being said. But what if a printer wasn't sure of the author's intentions? What to do, for example, with rhetorical questions? Even today there is uncertainty: how should we punctuate the response

How would

I

know

â ending with a question mark or an exclamation mark? (This was one of the motivations for the interrobang, which did both at once: see

Chapter 20

.) The speaker is using a question form but not really asking a question at all.

In the First Folio we see many examples where the compositors had no idea what was going on. We see utterances that are clearly questions being ended with exclamation marks, as when in

Coriolanus

(1.1.221) a Messenger arrives and speaks to Martius:

Mess

. Where's

Caius Martius

?Mar

. Heere: what's the matter!

We see exclamatory utterances being ended with question marks, as when in

Julius Caesar

(3.4.39) Portia reflects on her situation:

Aye me! How weake a thing

The heart of woman is?

And we see hugely exclamatory utterances with non-exclamatory punctuation, as when in

Hamlet

(1.5.80) the Ghost cries out:

Oh horrible Oh horrible, most horrible:

Not quite the required dramatic effect, using a comma and a colon.

The uncertainty over the use of an exclamation mark is hardly surprising, as this became popular in English only during the 1590s, even though its existence had been recognized for decades. It's one of the marks listed in John Hart's book about the reforms he felt were needed in English orthography,

The opening of the unreasonable writing of our Inglish toung

, published in 1551. He called it âthe wonderer', and distinguished it from the question mark or âasker'. In

An Orthographie

, he went further, suggesting that both of these marks should be used before as well as after a sentence, because the asking and wondering tunes are there from the sentence beginning. It was a nice idea, but it never caught on in English (though it did in Spanish, where a sentence-opening inverted ? and ! were introduced by the Spanish Academy in 1741). A nineteenth-century printer, George Smallfield, actually recommended using the Spanish inverted marks in English, but he was a lone voice.

Similar problems of consistency and interpretation affected the other punctuation marks that were being increasingly used at the end of the sixteenth century, such as the apostrophe, the semicolon, and quotation marks. I'll tell their stories individually in later chapters, but the general picture should be clear. Writers were ready to use the new array of punctuation marks, but were unsure about how to do so. Books on orthography were more interested in spelling reform than punctuation, and when they did give advice it was often

partial and conflicting. Schoolteachers simply followed whatever book they had available. So, where should writers look for guidance to sort out the mess? Increasingly, they copied examples of what they felt was best practice, which was the punctuation as presented in widely read printed books. And because identical copies of a book were now available in large numbers, authors slowly but surely produced manuscripts that followed the same set of printing-house conventions.

Power to the printers. The compositors weren't sure how to use some of the new marks any more than their authors were, but they were in the more powerful position. There was no policy of sending proofs out to authors to check â that came a long time after. What a compositor typeset, people would read, whether it was what the author intended or not. And after a century of experience, printers were becoming more confident. During the 1580s we see evidence of them starting to replace punctuation marks in an author's copy. It's the beginning of a tradition of âprinters know best', which later evolved into âpublishers know best', and led to a new professionalism, in which editors and copy-editors took the primary responsibility to guarantee the production of texts that were clear and consistent, and reflected the identity of a publishing house. For the most part, authors didn't care. Unsure of their own practice, they were happy to leave such matters as spelling, layout, and punctuation to the professionals. But not all were happy â a new generation of writers on the English language least of all.