Map of a Nation (18 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

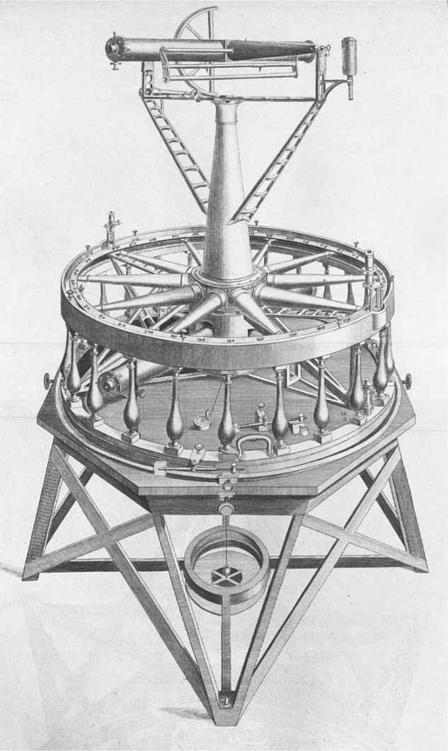

15. The Great Theodolite.

Early theodolites consisted of sights, without lenses, that were attached to a circular scale to measure the angles of observations. The instrument that Ramsden began constructing for the Paris–Greenwich triangulation was of a new generation. It was huge. An enormous ‘brass circle, three feet in

diameter

’ lay at its heart. On this circle a scale was engraved from which the angle of a sight line’s horizontal position could be read. This scale was more minute than any in existence: the circle’s vastness and Ramsden’s skill meant that it boasted divisions down to ‘about 1/24,000 part of an inch’, measuring angles

to one second of arc. Micrometers were fixed to the scale to render these infinitesimally tiny angular measurements clearly visible. And the theodolite was not just restricted to the measurement of horizontal angles. It boasted

two

telescopes, each containing Dollond’s famous achromatic lenses. The lower telescope was positioned just beneath the brass circular scale and could only move horizontally. But the upper telescope was positioned above the scale, and it swivelled both horizontally and vertically beside an upright

semicircular

scale that measured the angle of its vertical elevation. This meant that the theodolite could measure heights as well as distances, and even look to the stars.

Numerous further refinements ensured that Ramsden’s theodolite was the most accurate in the world: spirit levels, internal lanterns, and joints so well constructed that the instrument was found to ‘turn round very smoothly, and is perfectly, or at least as to sense, free from any central shake’. And the theodolite came with an entourage of accoutrements: a stand, a scaffold and crane to lift the instrument’s enormous bulk as high as thirty-two feet,

pulleys

, ropes, a portable observatory made from oak and canvas, a travelling case, and a tent and canopy to guard against the elements. Later it would even be given its own customised carriage with spring-suspension to protect it from jerks and jolts.

Such unprecedented sophistication took Ramsden a long time to produce, much longer than either he or Roy had predicted. Years passed and Roy became infuriated at the delay, while Ramsden complained that his time and effort was quite disproportionate to the remuneration. An accident in the final year of the theodolite’s construction postponed its completion even

further

. One of Ramsden’s workmen dropped a ‘large brass ruler’ on the central circular scale ‘when the divisions were nearly all cut’, damaging it to such a degree that the instrument-maker was ‘obliged … to take out the whole of the dividing and to begin entirely a new’. On 1 June 1787, Charles Blagden excitedly informed Joseph Banks that ‘Ramsden is hard at work upon General Roy’s instrument which it seems may be finished by the end of next week.’ But Ramsden’s health suddenly took a downturn and the theodolite was not finished until August. This delay and the bitterness it engendered would come back to haunt Ramsden and Roy both.

D

ESPITE THESE FRUSTRATIONS

for William Roy, the years after the completion of the base measurement were not devoid of activity. He wrote up a detailed report of his experiences on Hounslow Heath: the trauma of the wooden rods, the innovation of glass replacements and the resulting baseline measurement whose accuracy surpassed any previous such

operation

in Britain. He read his account before the Royal Society between 21 April and 16 June 1785, and was delighted to find himself the recipient of the Copley Medal, the Society’s highest accolade, for his efforts. And the fame that Roy had enjoyed during the baseline measurement continued. Newspapers reported the promotion of this ‘incomparable Engineer’ from lieutenant-colonel to colonel; his attendances at St James’s Palace, where he ‘kissed the King’s hand’; his election as a member of the Royal Society’s council; and the sole exemption of ‘our trusty and well-beloved

Lieutenan

t-Colonel

William Roy’ from a pay cut that affected every other military engineer in the kingdom.

Since Cassini de Thury had first mooted the idea of a triangulation between Greenwich and Paris, the French and English surveying parties had both found themselves treading on nationalist eggshells, repeatedly coming up against xenophobia and jingoism, despite Joseph Banks’s plea that scientists ‘ought not to hate one another [just] because the armies of our respective nations may shed each other’s blood’. Cassini de Thury’s initial memorandum had been careful to praise previous British achievements and flatter the monarch. But, replying in French, Banks had managed to offend him with an ill-phrased remark, ‘owing I suppose to the difficulty I have in Expressing my Ideas correctly according to the Idiom of your Language’. After this faux pas, Banks begged Blagden to take over the task of

communicating

with the French savants in their own language. Even Roy himself was not very friendly at first to his ‘fellow Labourers’, as he termed the French astronomers. Like many British scientists, he had a patriotic

attachment

to the theodolite and went to ‘some pains to investigate the degree of accuracy of the French trigonometrical operations’ as he felt ‘they certainly were not executed with the best Instruments’. By his own admission he was

not fond of small talk, and Roy’s communications with the French astronomers were perfunctory and devoid of niceties.

These nationalist irritations were considerably diminished when in September 1784 the progenitor of the whole project, Cassini de Thury, contracted smallpox and died. From the beginning Blagden had been

sceptical

about the French astronomer’s merits. ‘The

younger

Cassini,’ Blagden mused, referring to Cassini de Thury’s son, Jean Dominique (Cassini IV), ‘seems to possess more acuteness’ than his father ‘and has, I think, good ideas.’ Cassini de Thury’s death cleared the way for his son to take over direction of the French side of the project, and much better relations ensued between the British and French parties. Patient in the wait for Ramsden to finish the theodolite, Jean Dominique Cassini was charming and cooperative when the British were finally ready to begin the triangulation in 1787. The French had little to do themselves, as their side of the triangulation between Paris and the north coast of France had already been measured during the making of the

Carte de Cassini

. Some triangles needed confirming, but Cassini’s chief concern was coordinating the cross-Channel observations that would join together the French and English triangulations. The surveyor Pierre François André Méchain was appointed as Cassini’s assistant and both declared themselves charmed at the prospect of visiting London, to meet with its ‘illustres savans’ and discuss their instruments and methods. Cassini made the most of his trip, taking a shopping list to Jesse Ramsden’s Piccadilly workshop, where he commented to a bystander that ‘this man is an electrical machine which has only to be touched to emit sparks’. Blagden, for his part, proposed that Cassini and Méchain should be made foreign members of the Royal Society.

In July 1787 the British finally began their triangulation. After preliminary arrangements, the theodolite was in use by August. The surveyors planned to observe triangles that stretched from the wooden pipes that marked the ends of the Hounslow Heath baseline right down to the south coast of Kent. But the triangulation got off to a bumpy start. A telescopic surveying

instrument

like Ramsden’s three-foot theodolite greatly enhanced the distance and precision achievable by naked eyesight. But such sophistication often meant that surveyors found that they needed to relearn to see. We can imagine

William Roy positioning the instrument over the eastern extremity of the baseline, training the telescope in the general direction of the spire of Banstead Church ten miles away, and placing his right eye against the

eyepiece

to find … only black shadow. Finding the eye’s optimum position in front of the telescope took time. And when the sights had been carefully focused on their target, and Banstead Church spire had come into view in the centre of the grid of wires that bisected the lens, it was all too easy to lose sight of one’s prey with the slightest nudge of the instrument. It was also an acquired skill to manipulate the micrometer that allowed the sight line’s angle to be deduced to the minutest degree. Surveying in the era of such superior instruments and methods was a highly developed craft.

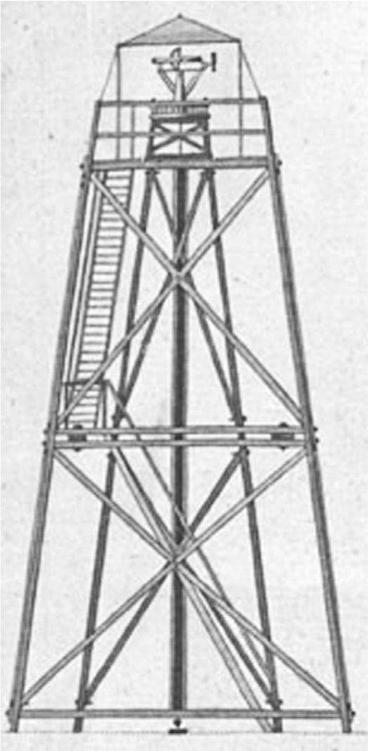

16. The scaffolding used to hoist the theodolite to the required height, during the Paris–Greenwich triangulation.

But soon Roy had tamed the theodolite, and at the eastern end of the baseline its sights were being successfully trained on trig points at Windsor Castle in the west, Hanger Hill Tower to the north-east and the summit of St Ann’s Hill in Chertsey. Roy and his military assistants then carted the three-foot, 200-pound, nerve-janglingly intricate instrument to each of these

trig stations. Where necessary, they winched it to the top of towers or spires or up its own thirty-two-foot scaffolding. Roy then clambered up to the theodolite and trained its telescopes back onto Hounslow Heath, to verify the earlier observations. In a notebook he carefully recorded each angle and the temperature of the air, to allow him to deal in his equations with any

expansion

or contraction in the instrument’s metals. He directed the theodolite’s sights over towards Hundred Acres near Banstead, then to Norwood, Greenwich Observatory and Severndroog Castle. The same rigmarole was repeated at trig point after trig point, until triangles of sight lines were plotted across Sussex and Kent to Botley Hill and Wrotham Hill.

The process was desperately slow. Some of Roy’s observations required him to identify trig points more than thirty miles away, requiring

exceptionally

clear weather conditions and consummate skill at manipulating the theodolite’s telescopes and scales. After a month or so, Blagden wrote

apologetically

to Cassini: ‘General Roy est à quelque distance de Londres … mais, à ce qu’on me dit, il n’est pas encore fort avancé.’

2

Uncomfortable at having kept the French surveyors waiting so long, Blagden suggested to Roy that he halt the mainland triangulation at Wrotham Hill and head straight for the coast to begin the cross-Channel observations with the French. Roy and Cassini both proved amenable to this idea (Roy even tried to pass it off as his own), and in the last week of September they met face to face in Dover. Roy proved a magnanimous host. He gave his guests a guided tour of the ‘antique and half-ruined’ Dover Castle and proudly showed off the workings of the ‘Great Theodolite’. It was an efficient and productive visit too. Leaning over maps spread out on a large oak table, with Blagden

translating

, Roy and Cassini finalised dates, sites and techniques for the cross-Channel observations.

Cassini’s party left Dover at the end of September to position themselves along the northern French coastline. Roy and Cassini had agreed that ‘

reverbaratory

[

sic

] lamps’ or ‘white lights [with] extraordinary brilliancy’ should be attached to the surveying flagstaffs to illuminate them through the thick

fog that often hung over the Channel. To distinguish their own lights from any others on the horizon, they ‘placed [one lamp] over the other’. On 29 September, Cassini lit his signals at the top of the tower at Dunkirk. Roy grumbled that he did so ‘somewhat earlier than the times appointed’, taking the British surveying team at Dover by surprise. When the flares were lit again, Roy was ready but the air was ‘not sufficiently clear to permit us to intersect it with the Wires of the Telescope’. Over the next three weeks, the French and British alternately lit signals and conducted observations that criss-crossed over the Channel, between Dover Castle and the windmill at Fairlight Head on England’s south coast, and Montlambert (a hilltop near Boulogne), Cap Blanc Nez, Dunkirk tower and Calais’s Notre Dame Church, all on the north coast of France. The lamps were a great success. Cassini reported incredulously that ‘he hardly expects to be believed, when he tells that he observed one from Calais, which was fired on the opposite shore, about 40 miles off, and in bad weather’. Stormy weather on 2 October was ‘very unfavourable for Observations’, but it did not prevent Roy from successfully observing the flares at Calais and Blanc Nez. The sight of such bright lights seen irregularly through the vapour above the Channel must have been intriguing to locals, somewhat confusing to mariners and extremely worrying to smugglers.