Mark Griffin (47 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

Metro’s front office believed that the superlative cast that was assembled might distract the eagle-eyed censors from the plot’s tawdrier elements. In addition to Kirk Douglas,

Two Weeks

would feature Edward G. Robinson, Oscar-winner Claire Trevor, Cyd Charisse, and the eternally poised George Hamilton, who immediately felt ill at ease as the picture’s resident bad ass, Davie Drew.

Two Weeks

would feature Edward G. Robinson, Oscar-winner Claire Trevor, Cyd Charisse, and the eternally poised George Hamilton, who immediately felt ill at ease as the picture’s resident bad ass, Davie Drew.

“The character I was playing was a real bad boy—a cross between James Dean and maybe Warren Beatty,” says Hamilton:

I got the role because of Minnelli, but it wasn’t really me and it wasn’t something that I was terribly comfortable playing. But all they wanted me to do was come to Rome and shoot . . . though they were constantly getting behind. So, they just gave me a Ferrari and a lot of per diem, and I drove around Rome till three or four in the morning because we were doing night shooting and they never called me. They just had me on stand-by all night. So, I didn’t get to see much of the shooting in Rome. I was just there and living the life of what was going on . . . the real

La Dolce Vita

.

La Dolce Vita

.

It was an interesting period because it was Elizabeth Taylor and

Cleopatra

and that whole era. So, I was right in the middle of all of that. But as far as filmmaking goes, I think the picture that Kirk had done earlier with Minnelli [

The Bad and the Beautiful

] was much more on the money than this. [

Two Weeks

] was this kind of almost Fellini-esque movie. And it really wasn’t grounded in reality. It wasn’t even grounded in movie reality. It was almost like a comment on another era and another time, and that time happened to be

La Dolce Vita

. But it really didn’t ring true—our movie. It seemed to me very phony as a film. It had all of that back projection going on. . . . When you have those techniques and the times were changing, all of a sudden, it looked very old-fashioned to me. . . .

Cleopatra

and that whole era. So, I was right in the middle of all of that. But as far as filmmaking goes, I think the picture that Kirk had done earlier with Minnelli [

The Bad and the Beautiful

] was much more on the money than this. [

Two Weeks

] was this kind of almost Fellini-esque movie. And it really wasn’t grounded in reality. It wasn’t even grounded in movie reality. It was almost like a comment on another era and another time, and that time happened to be

La Dolce Vita

. But it really didn’t ring true—our movie. It seemed to me very phony as a film. It had all of that back projection going on. . . . When you have those techniques and the times were changing, all of a sudden, it looked very old-fashioned to me. . . .

So, there we were in Rome, but we were still very much Hollywood at the same time. I never felt as though we were shooting scenes about something real.

2

2

Back projection aside, Minnelli’s biggest challenge on

Two Weeks

appears to have been competing with himself. For the specter of

The Bad and the Beautiful

hovers over the picture. At one point, Minnelli goes full tilt self-reflexive: Kirk Douglas’s Jack Andrus screens clips of Kirk Douglas in

The Bad and the Beautiful

. Later, in a dramatically charged sequence, Jack’s reckless driving—with a hysterical Carlotta along for the ride—seems intent on recapturing the effect of Lana Turner’s automotive meltdown. And even composer David Raksin can’t refrain from appropriating portions of his haunting

Bad and the Beautiful

score for

Two Weeks

.

Two Weeks

appears to have been competing with himself. For the specter of

The Bad and the Beautiful

hovers over the picture. At one point, Minnelli goes full tilt self-reflexive: Kirk Douglas’s Jack Andrus screens clips of Kirk Douglas in

The Bad and the Beautiful

. Later, in a dramatically charged sequence, Jack’s reckless driving—with a hysterical Carlotta along for the ride—seems intent on recapturing the effect of Lana Turner’s automotive meltdown. And even composer David Raksin can’t refrain from appropriating portions of his haunting

Bad and the Beautiful

score for

Two Weeks

.

“They were doing this sort of, kind of like a sequel to

The Bad and the Beautiful

. Could they do it twice? That was sort of the idea,” remembers actress Peggy Moffit:

The Bad and the Beautiful

. Could they do it twice? That was sort of the idea,” remembers actress Peggy Moffit:

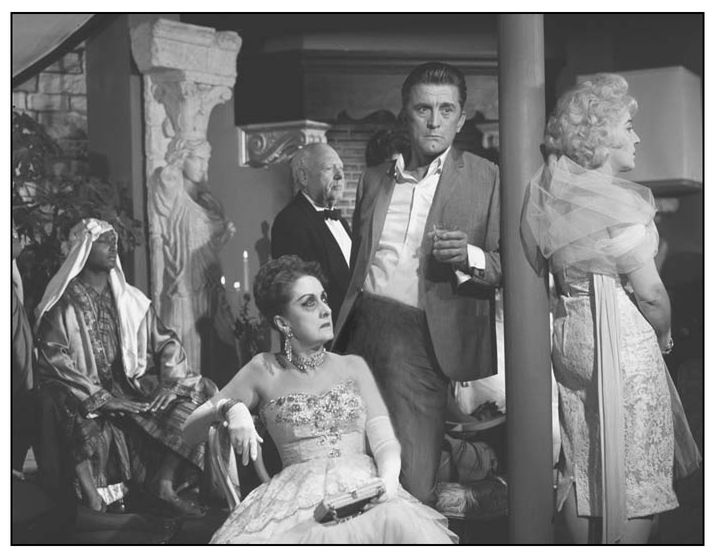

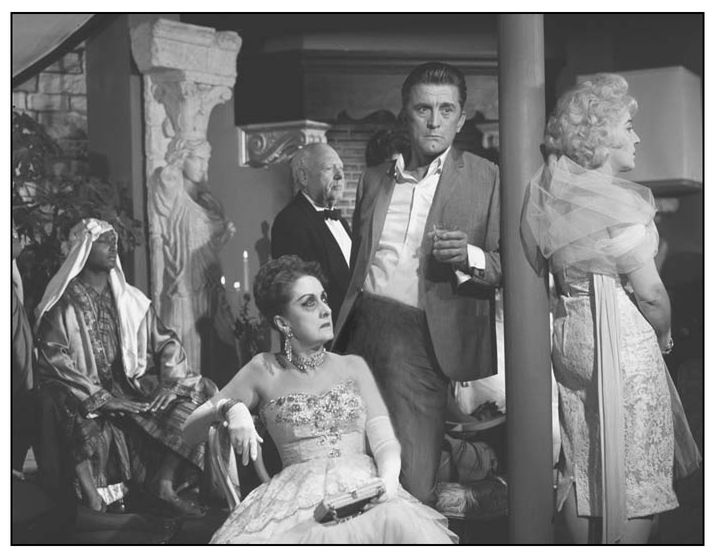

Kirk Douglas in search of a little

La Dolce Vita

in Minnelli’s

Two Weeks in Another Town

. The film would find favor with the

Cahiers du Cinéma

crowd and a young film critic named Peter Bogdanovich, who said that Minnelli’s Roman bacchanal was “surely the ballsiest, most vibrant picture he has signed.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

La Dolce Vita

in Minnelli’s

Two Weeks in Another Town

. The film would find favor with the

Cahiers du Cinéma

crowd and a young film critic named Peter Bogdanovich, who said that Minnelli’s Roman bacchanal was “surely the ballsiest, most vibrant picture he has signed.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

There was a sequence in

Two Weeks

that was supposed to be a very stylish orgy in Rome. I was friends with John Houseman and he said, “I want you to meet Vincente Minnelli about this part. So I did and was cast. It was a glorified-dress extra kind of thing. . . . It turned out to be a totally soporific scene that does not come off at all. When I look at Vincente’s other movies, I’m impressed with how wonderfully staged and thought out they were, but my impression was that he had totally run dry on this one—though everybody was absolutely mesmerized by him and revered him, from wardrobe and make-up to the grips and gaffers. It was like “his holiness.” They would do whatever he asked. . . .

Two Weeks

that was supposed to be a very stylish orgy in Rome. I was friends with John Houseman and he said, “I want you to meet Vincente Minnelli about this part. So I did and was cast. It was a glorified-dress extra kind of thing. . . . It turned out to be a totally soporific scene that does not come off at all. When I look at Vincente’s other movies, I’m impressed with how wonderfully staged and thought out they were, but my impression was that he had totally run dry on this one—though everybody was absolutely mesmerized by him and revered him, from wardrobe and make-up to the grips and gaffers. It was like “his holiness.” They would do whatever he asked. . . .

I remember Minnelli staring at the cocktail table where Leslie Uggams was sitting and he would twitch away and say nothing. We would be standing there for hours and then he would finally say something to a set decorator and it would be about something he didn’t like—like the roses on the coffee table.

He wanted gladiolas. And so, somebody would go scurrying all over the MGM lot to try and find a bunch of fake gladiolas. . . . I walked away thinking, “He’s fooled everybody . . . he’s got no talent whatsoever.”

He wanted gladiolas. And so, somebody would go scurrying all over the MGM lot to try and find a bunch of fake gladiolas. . . . I walked away thinking, “He’s fooled everybody . . . he’s got no talent whatsoever.”

Well, of course, that’s absurd. He had great talent. I think he did great things, but

Two Weeks

was utterly deadly. And so, this idea of debauchery and wild car chases and passion and all of that certainly did not permeate the film—or the set, for that matter. Nobody lit anybody’s fire on that one. Trust me.

3

Two Weeks

was utterly deadly. And so, this idea of debauchery and wild car chases and passion and all of that certainly did not permeate the film—or the set, for that matter. Nobody lit anybody’s fire on that one. Trust me.

3

Whatever sparks may have existed in Minnelli’s original cut of

Two Weeks in Another Town

were snuffed out by Joseph Vogel after he screened the film and ordered a drastic re-edit. Considerable cuts were made without consulting either Houseman or Minnelli. After Houseman fired off an angry letter to MGM’s legal department, the producer was allowed to reshape the film—but he was only allowed to use Vogel-approved footage. Understandably, Minnelli was outraged that

Two Weeks

had been wrested away from him. In its final form, the story was missing so much meat that the result is not so much a complete movie but 107 minutes of rushes.

Two Weeks in Another Town

were snuffed out by Joseph Vogel after he screened the film and ordered a drastic re-edit. Considerable cuts were made without consulting either Houseman or Minnelli. After Houseman fired off an angry letter to MGM’s legal department, the producer was allowed to reshape the film—but he was only allowed to use Vogel-approved footage. Understandably, Minnelli was outraged that

Two Weeks

had been wrested away from him. In its final form, the story was missing so much meat that the result is not so much a complete movie but 107 minutes of rushes.

“The picture should have been better than it was,” Cyd Charisse reflected years later. “When I finally saw it, I couldn’t make heads or tails of the story—it was so disconnected—and I’d been in it.”

4

The reckless, pre-release editing pared away not only wholesale chunks of the narrative but revealing bits of character. In the studio-sanctioned version, Charisse’s Carlotta comes off as a soulless, self-absorbed virago. In Minnelli’s version, the character had more shading. “Last time I counted, I had over a thousand dresses,” Carlotta admits in a deleted sequence. “More than four hundred suits. Including the first suit I ever owned—a hound’s tooth gabardine I bought in Macy’s basement for nineteen ninety-five. It’s a trait of mine. I can’t stand to give up anything I’ve ever owned.” With the back story removed, Carlotta’s clinging to her ex-husband seems inexplicable and odd—like so much of the film in its truncated form.

4

The reckless, pre-release editing pared away not only wholesale chunks of the narrative but revealing bits of character. In the studio-sanctioned version, Charisse’s Carlotta comes off as a soulless, self-absorbed virago. In Minnelli’s version, the character had more shading. “Last time I counted, I had over a thousand dresses,” Carlotta admits in a deleted sequence. “More than four hundred suits. Including the first suit I ever owned—a hound’s tooth gabardine I bought in Macy’s basement for nineteen ninety-five. It’s a trait of mine. I can’t stand to give up anything I’ve ever owned.” With the back story removed, Carlotta’s clinging to her ex-husband seems inexplicable and odd—like so much of the film in its truncated form.

“

Two Weeks in Another Town

was a disappointment,” Kirk Douglas admitted forty-five years after he made a valiant attempt to rescue the film from the butcher’s block:

Two Weeks in Another Town

was a disappointment,” Kirk Douglas admitted forty-five years after he made a valiant attempt to rescue the film from the butcher’s block:

I wrote to Vogel, even though I was just an actor in it. . . . I argued with him, told him that if he wanted to make a family picture, he should have never made

Two Weeks in Another Town

. I went to [editor] Margaret [Booth], pleaded with her. She agreed with me that what they were doing was wrong, but she

worked for MGM and was frightened of losing her job. She burst into tears. . . . They cut most of the exciting scenes. I felt this was an injustice to Vincente Minnelli, who’d done a wonderful job with the film. And an injustice to the paying public, who could have the experience of watching a very dramatic, meaningful film. They released it that way . . . emasculated.

5

Two Weeks in Another Town

. I went to [editor] Margaret [Booth], pleaded with her. She agreed with me that what they were doing was wrong, but she

worked for MGM and was frightened of losing her job. She burst into tears. . . . They cut most of the exciting scenes. I felt this was an injustice to Vincente Minnelli, who’d done a wonderful job with the film. And an injustice to the paying public, who could have the experience of watching a very dramatic, meaningful film. They released it that way . . . emasculated.

5

Any positive assessments of the film tended to be drowned out by the vocal majority: “The whole thing is a lot of glib trade patter, ridiculous and unconvincing romantic snarls and a weird professional clash between actor and director that is like something out of a Hollywood cartoon,” Bosley Crowther wrote in the

New York Times

.

6

New York Times

.

6

Two Weeks in Another Town

did find some important champions, including twenty-three-year-old future director Peter Bogdanovich, who reviewed it for

Film Culture

and saluted it as

did find some important champions, including twenty-three-year-old future director Peter Bogdanovich, who reviewed it for

Film Culture

and saluted it as

a picture of perversion and glittering decay that in a few precise and strikingly effective strokes makes Fellini’s

La Dolce Vita

look pedestrian, arty and hopelessly socially-conscious. . . . It could be said that all the characters are two-dimensional, but it is such an obvious remark that only an idiot could imagine that Minnelli didn’t know exactly what he was doing: a grand melodrama, filled with passion, lust, hate, and venom, surely the ballsiest, most vibrant picture he has signed.

7

La Dolce Vita

look pedestrian, arty and hopelessly socially-conscious. . . . It could be said that all the characters are two-dimensional, but it is such an obvious remark that only an idiot could imagine that Minnelli didn’t know exactly what he was doing: a grand melodrama, filled with passion, lust, hate, and venom, surely the ballsiest, most vibrant picture he has signed.

7

32

Happy Problems

DENISE WAS IN. After only a few years of marriage to Minnelli, she was already being hailed as “Hollywood’s Josephine”—as in the guilelessly charming French empress. The comparison suited Beverly Hills’ busiest hostess just fine. “My favorite historical personage is Josephine,” Denise told

Los Angeles Times

reporter John Hallowell. “She was an elegant swinger, darling. Napoleon, he was ze general; Josephine was the

influence

. And she was not stuffy.”

1

Neither was Denise, who could certainly swing with the best of them. She dished with Truman Capote, dined with Vanessa Redgrave, and got the guest room ready for the president’s daughter, Lynda Bird Johnson. Denise rubbed elbows with everyone—from Hollywood royalty, such as Jennifer Jones Selznick, to real royalty, such as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor.

Los Angeles Times

reporter John Hallowell. “She was an elegant swinger, darling. Napoleon, he was ze general; Josephine was the

influence

. And she was not stuffy.”

1

Neither was Denise, who could certainly swing with the best of them. She dished with Truman Capote, dined with Vanessa Redgrave, and got the guest room ready for the president’s daughter, Lynda Bird Johnson. Denise rubbed elbows with everyone—from Hollywood royalty, such as Jennifer Jones Selznick, to real royalty, such as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor.

The parties she threw were legendary, and the self-described “international nomad” proved to be as adept at assembling an all-star cast as her husband. “I am basically a frustrated David Merrick,” Denise admitted. “I don’t invite people. I

cast

people for my parties—the players, supporting players, chorus girls and boys, interesting character actors. Every party is like opening night.” And there was no mistaking who the headliner was. As columnist Joyce Haber once noted, the supersonic jet-setter was a walking cinematic event, who was “personally dressed by Donald Brooks and Jimmy Galanos, bejeweled by David Webb, arranged by Valerian Rybar, profiled by Rex Reed, photographed by Cecil Beaton and carefully bedecked by everyone who is anyone.”

2

cast

people for my parties—the players, supporting players, chorus girls and boys, interesting character actors. Every party is like opening night.” And there was no mistaking who the headliner was. As columnist Joyce Haber once noted, the supersonic jet-setter was a walking cinematic event, who was “personally dressed by Donald Brooks and Jimmy Galanos, bejeweled by David Webb, arranged by Valerian Rybar, profiled by Rex Reed, photographed by Cecil Beaton and carefully bedecked by everyone who is anyone.”

2

On the arm of an Oscar-winning husband, Denise was A-list all the way. And thanks to his wife, Minnelli was back on the map socially. All of the

balls, black-tie events, and blowouts at the Bistro that he attended landed Vincente’s name—or at least “The Minnellis,” in the columns on an almost daily basis.

balls, black-tie events, and blowouts at the Bistro that he attended landed Vincente’s name—or at least “The Minnellis,” in the columns on an almost daily basis.

“That marriage was very important for both of them because it established her social position in Los Angeles and New York and the rest of the world, which is what she always wanted, and also, she had such an aggressive and powerful personality that she was able to really revive Vincente’s career,” says one who witnessed Denise’s meteoric ascent.

3

3

It was Denise who was the driving force behind Venice Productions, the independent production company that she and Vincente founded in 1962 (“Venice” was an amalgam of their names). Three Minnelli movies would be produced under the Venice banner (

The Courtship of Eddie’s Father

,

Goodbye, Charlie

, and

The Sandpiper

). Although husband and wife were supposed to be equal partners in the venture, it soon became apparent that one of the participants seemed to have the upper hand where financial matters were concerned—and it was not the director of

Meet Me in St. Louis

.

The Courtship of Eddie’s Father

,

Goodbye, Charlie

, and

The Sandpiper

). Although husband and wife were supposed to be equal partners in the venture, it soon became apparent that one of the participants seemed to have the upper hand where financial matters were concerned—and it was not the director of

Meet Me in St. Louis

.

“Denise demanded things from the studios and she pushed and pushed beyond anything that you can imagine,” says designer Luis Estevez. “Although they had a great house right on Sunset Boulevard, Denise knew from the beginning that Vincente was never going to make enough money for her.”

4

Even those in Denise’s inner circle would blame her for the fact that Minnelli was passed over when Warner Brothers went shopping for a director for their film version of

My Fair Lady

. As the story goes, Denise pressured Vincente to ask for too much money and he ended up outpricing himself. Warners snapped up George Cukor for $300,000, and Minnelli lost his chance to direct what could have been one of the most important films of his career.

4

Even those in Denise’s inner circle would blame her for the fact that Minnelli was passed over when Warner Brothers went shopping for a director for their film version of

My Fair Lady

. As the story goes, Denise pressured Vincente to ask for too much money and he ended up outpricing himself. Warners snapped up George Cukor for $300,000, and Minnelli lost his chance to direct what could have been one of the most important films of his career.

But the “hostess par none” wasn’t about to miss any opportunities. In the ’60s, Denise’s socializing hit a peak. As one of her former intimates recalls:

That’s when she started on her quest to meet all of the rich and powerful women of Hollywood—the ladies who lunch, shall we say. And Denise knew how to work them right around her finger. She had the fashionable clothes. She knew everybody. She threw these lavish parties and hosted these lunches. And all the while, she was fishing and scheming and turning herself into “Denise, Inc.” She had a good vehicle with Minnelli, and, of course, being married to him, she was living in the midst of the most powerful people in Hollywood—where he was very highly regarded and should have been. Later on, when Denise decided it was time to move on, she saw her chance and took it.

5

5

Other books

Squishy Taylor in Zero Gravity by Ailsa Wild

The Rose Bride by Nancy Holder

Cowboy Save Me: By Judith Lee (Tiller Brothers Book 1) by Lee, Judith

Three Men and a Bride by Carew, Opal

Mr. Wright & Mr. Wrong: A BWWM Romance by Camilla Stevens

The Magician's Wife by Brian Moore

Finding My Way Home by Alina Man

Forgive Me, Alex by Lane Diamond

Soothsayer: Magic Is All Around Us (Soothsayer Series Book 1) by Allison Sipe

Highland Mist by Rose Burghley