Meatonomics (17 page)

Authors: David Robinson Simon

Of course, these diseases have various contributing causes, including genetics and nondietary environmental issues like exposure to toxins. But in the case of the big three—cancer, diabetes, and heart disease—diet seems to be behind one-third or more cases.

28

It's certainly

possible

to eat a half pound of meat every day and never develop disease. It's also possible to smoke two packs of cigarettes a day and never get emphysema or lung cancer. But in both cases, just like trying to beat a casino at its own game, the odds are against it in the long run.

When the price of a product falls, we generally buy more of it. When the price rises, we buy less. That's the law of demand in a nutshell. Just how closely our behavior tracks a good's price depends on many factors, including our disposable income, how badly we want it, whether substitutes are available, and so on. Take cigarettes. One study found that a 10 percent increase in cigarette prices lowered the number of high school students smoking by 3.5 percent.

29

As simple as the law of demand is, it has profound implications for meat and dairy consumption. That's because industrial production methods and other producer-spurred phenomena of meatonomics keep prices artificially low, and low prices mean more people in line at the butcher counter.

Recall that the inflation-adjusted retail prices of animal foods have declined over the past century. Since 1935, ham is cheaper by 48 percent and steak by 20 percent.

30

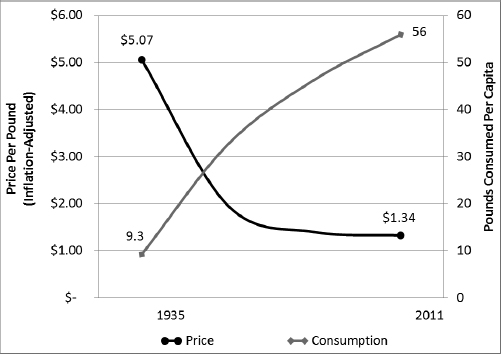

As the law of demand predicts, the steady drop in prices causes an upswing in consumption. Since 1935, US per capita meat consumption (for all meat types) rose by an astonishing 95 percent. In the chicken category, while prices fell to one-quarter of their original level, per capita consumption jumped sixfold.

Chart 6.1

shows the dramatic relationship between US chicken prices and consumption during this period. (Note that because this consumption increase is measured on a per-person basis, it is unrelated to growth in the US population.)

CHART 6.1

US Chicken Prices and Per Capita Consumption, 1935–2011

Of course, it's not fair to give

all

the credit for our high meat consumption to low prices. After all, people eat meat for reasons other than price—they might like the taste, or they might think it's good for them. Americans' disposable incomes have risen in the past century, which has helped spur consumption. And as we've seen, consumers are constantly hit with aggressive government messaging that urges us to eat more meat and dairy. However, while these non-price factors are important drivers of demand, price is also important. How important? Luckily, economists have a way to determine just

how

significant price is among the various factors that affect demand. It's relatively easy to measure the effect of price changes on quantity demanded in a manner that takes into account the effect of other factors.

The technical term is

price elasticity of demand

, and it describes how closely demand for a good follows its price. If a 1 percent change in price causes a 1 percent difference in quantity demanded, demand is said to be elastic (or technically, unit elastic). If a 1 percent price change causes less than a 1 percent demand change, as in the cigarette example above, demand is relatively inelastic. In other words,

the more

elastic

the demand for a good, the more a price increase will cause quantity demanded of the good to drop.

A number of factors influence a particular good's price elasticity, including the availability of substitutes and the good's necessity (real or perceived). For example, because insulin is necessary for those with diabetes and there are no substitutes, demand for insulin might well be perfectly inelastic—that is, consumers might buy the same quantity regardless of price changes. The availability of substitutes is often a big factor in a good's price elasticity. As a general category, soft drinks have demand elasticity of about 0.8, which is relatively inelastic and means people want soda enough that price increases have less than a one-to-one effect in lowering sales.

31

However, because of widespread substitutes within the soft drink category, the Coca-Cola brand has price elasticity of 3.8.

32

This means that if Coke prices were to go up by 10 percent, consumers would switch to other brands or flavors and cause Coke sales to go down by a whopping 38 percent. Demand for Coke, then, is highly elastic—and brand loyalty of its drinkers, in the face of price hikes, is flatter than a week-old can of the stuff.

A hefty pile of studies (419 at last count) measures the price elasticity of demand for animal foods—that is, the relationship between prices and consumption. In 2010, a meta-study determined that a 1 percent change in the price of beef causes American consumption to change by about 0.75 percent.

33

In other words, notwithstanding all the other reasons why people buy beef—including marketing, taste, and nutritional beliefs—a 10 percent price change will shift consumption by about 7.5 percent. The study found that dairy has demand elasticity of 0.65, meaning that a 10 percent price change in dairy products causes consumption to change by about 6.5 percent.

34

Other animal foods are less elastic. A 10 percent rise in the price of eggs, for example, causes only a 2.7 percent drop in consumption. One reason why demand for eggs is less elastic than that for dairy is probably the perceived lack of egg substitutes—you might drink soy milk instead of cow's milk, but you're less likely to make a fried egg out of egg replacer.

35

(Although the idea that substitutes are lacking is really

a problem of perception; tofu, for example, makes a mean breakfast scramble.)

The weighted-average elasticity rate for all animal foods is about 0.65, based on the aggregate wholesale, or production, values of beef, pork, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy consumed in the United States yearly.

36

That is, on average, a 10 percent change in the retail price of an animal food causes a 6.5 percent consumption change. While this

relatively inelastic

figure means that price changes in animal foods have less than a one-to-one effect on quantity demanded, price is nevertheless still quite important as a driver of demand. As animal science professor Marta Rivera-Ferre notes, “consumer demand [for animal foods] is not linked with the actual biological needs of the human organism

but with prices.

”

37

With this elasticity figure in hand, we can make some curious observations about the effect of meatonomics on Americans' consumption of animal foods.

Economists are often interested in whether economic phenomena (such as a rise in consumption) are more supply driven (pushed by producer behavior) or demand driven (spurred by consumer income and preferences). In the case of animal food production, retail prices are low in large part because producers have gotten good at minimizing production costs through practices like hyper-confining animals and producing meat and dairy in high volumes to achieve economies of scale.

38

The elasticity data above suggest that retail prices are a large factor (although not the only factor) in Americans' decisions to buy animal foods. Since producers' cost-cutting behavior is a major driver in rock-bottom prices, it is also a major driver of consumer consumption. As professor Rivera-Ferre writes:

It is wrong to believe that [animal food] production systems are . . . driven by consumer demands. It is probably more plausible the other way around, that the production systems are the ones that determin[e] and create the market. Thus, consumers adjust themselves to the offer, and not the other way around.”

39

Now, take this supply-driven influence on price and combine it with the routine use of misleading or confusing information by industry and government to sell animal foods (as seen in the book's first half). It's a double whammy. Consumers have faulty information, which makes fully informed choices nearly impossible,

and

we are seduced by artificially low prices. The combo leads to an almost preordained result: we consume much more animal foods than we would under more balanced and honest circumstances.

Using the elasticity figure above, we can estimate how consumption would be affected if retail prices reflected animal foods' true costs. We've seen that if these costs were internalized, requiring producers to pass all or most of them on to consumers rather than imposing them on society in roundabout ways, the true retail price of these products would soar to roughly $665 billion yearly from $251 billion. Thus, shifting all the externalized costs onto animal food producers would nearly triple animal foods' retail prices.

If a 1 percent price hike lowers consumption of animal foods by an average of 0.65 percent, simple math suggests a 170 percent price increase would reduce consumption by the maximum of 100 percent.

40

Would the entire country really stop buying meat and dairy if prices went up this much? No. The reason: some consumers

really

like steak and will pay almost anything for it. Nevertheless, it's clear that the act of shifting external costs to producers, with its ensuing price hikes, would lead to a sheer drop in consumption. Conversely, and more importantly, as long as the prices of animal foods stay

artificially low

, people will keep consuming much more of these goods than they would otherwise.

You can't blame consumers, because they're merely responding rationally to the cues that meatonomics provides. Under these cues, Americans consume much more animal foods than we would otherwise and considerably more than the government recommends. We've seen that Americans in practically every demographic group eat more from the USDA's meat group than they should—by as much as two-thirds above the USDA-recommended levels (see

table 2.1

in

chapter 2

). Consider some of the side effects of this excessive consumption.

On a top-ten list of the worst health consequences of high meat and dairy consumption, excessive intake of cholesterol and saturated fat ranks high.

41

These substances are dangerous to our bodies in an insidious way, like creeping rot in a ceiling that makes the whole thing come crashing down one day. Right off the bat, it's important to note that neither cholesterol nor saturated fat is a nutrient, hence there is no USDA recommended minimum requirement for either. In a 1,357-page report commissioned by the USDA as the basis for its nutritional recommendations, the National Academies' Institute of Medicine notes that saturated fats “are

not essential

in the diet” and “there is

no evidence

for a biological requirement for dietary cholesterol.”

42

Accordingly, the report says consumption of cholesterol and saturated fat should be “as low as possible.”

43

That's because, among other things, “any intake greater than zero will increase serum levels of low density lipoprotein cholesterol, an established risk for cardiovascular disease.”

44

The federal government's recognition that

any

amount of ingested cholesterol or saturated fat is harmful has led to recommended daily maximums for these substances: 20 grams of saturated fat and 300 milligrams of cholesterol. However, although consumption in these amounts is already, by the National Academies' definition, harmful, Americans routinely exceed these levels. Males between forty and forty-nine, on average, routinely consume 35 percent more cholesterol than indicated. The USDA does not publish age-related cholesterol maximums, but the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) does. Under EFSA guidelines, US teenagers ingest half again the recommended daily maximum of cholesterol for their age.

45

And as

table 6.2

shows, saturated fat consumption is over the already unhealthy level of 20 grams in virtually every US demographic group.

I was once a poster child for an unhealthy relationship with fat and cholesterol—and my story, ultimately, illustrates the upside of breaking that vicious bond. For most of my adult life, like the typical adult American, my total cholesterol was at or over 200 mg/dl. I took

a daily acid-reducing pill for years to combat chronic acid reflux, also known as Gastroesophageal reflux disease or GERD. In early 2008, I had a body mass index (BMI) of 25—the upper end of the healthy range. But after switching to a plant-based diet in the spring of 2008, my weight fell 10 percent, or about 17 pounds. My cholesterol dropped to 140. And with highly acidic animal products gone from my diet, the acid reflux ceased and I stopped the pills. These results might sound exceptional or apocryphal. They're not. They're normal, ordinary, and consistent with numerous clinical studies that compare omnivores and vegans.

46

TABLE 6.2

US Daily Reference Value and Actual Consumption of Saturated Fat

47