Meatonomics (14 page)

Authors: David Robinson Simon

Here's another way to think about the ratio of

prices

(what we pay at the cash register) to

costs

(all relevant expenses—whether paid or not). Over the past century, the large gains in production efficiency that accompanied the rise of industrial agriculture helped drive the retail prices of animal foods lower. The growth rate of chickens doubled

while the price per pound fell. However, as Milton Friedman famously observed, “There's no such thing as a free lunch.” In fact, the same gains in efficiency that reduce prices also increase externalized costs. Chickens develop faster in part because they're fed growth-promoting antibiotics, but those drugs cause costly antibiotic resistance when they end up in our food and our waterways, making it that much harder for us to fight off a slew of sicknesses—and leading to more time in the doctor's office. Animals packed in factories can be raised more cheaply than those raised on pasture, but separating animals from land means their waste must be collected and stored. Some of this waste ends up in our water supply and generates serious clean-up costs. Like a new car promotion that offers twelve months without payments, the price of factory farming has been deferred or ignored—but by no means eliminated.

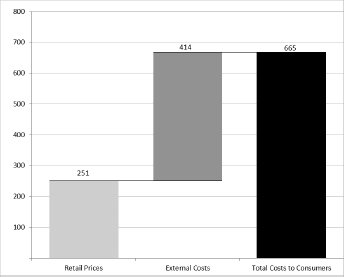

CHART 5.1

Total Costs to Consumers of Animal Foods (in billions of dollars)

If your diet tends toward the omnivorous, you might feel a sense of satisfaction that the prices you pay for meat and dairy are lower than they would be if external costs were imposed at the cash register. On the other hand, if you don't eat animal foods, you might feel relief that at least you're not participating in the system. But in either case, your wallet or pocketbook is going to feel the hit. That's because, like it or not, even though we don't pay them at the cash register, we all

do

incur the costs of animal food production in one way or another. For

example, even if you're lucky enough never to develop cancer, diabetes, or heart disease, you'll still help finance the treatment of those who do (unfortunately, many cases of these three diseases are attributable to consumption of meat, fish, eggs, and dairy).

Regardless of your eating habits, there's no way to avoid this steep burden. Don't eat fish? It doesn't matter—you'll still sustain your share of the expenses of overfishing, algal blooms, and other problems associated with fishing and fish farming. Don't eat meat or dairy? Vegetarians and vegans experience the externalized costs of animal foods at the same rate as the rest of society. Whenever someone buys a Big Mac, herbivores and omnivores alike pick up the tab for the burger's additional, externalized costs. This shifting of costs means each of us—rich or poor, sick or healthy, omnivorous or vegetarian—pays the true costs of these goods, not their producers. Further, contrary to the oft-repeated claim that producers pass low prices on to consumers, the externalization of costs does

not

really save us money because we simply pay the costs in other ways.

Of course, mass-producing just about any food generates external costs, and fruits and vegetables are no exception. Thus, growing crops for people imposes some of the same external costs on the environment that growing feed crops does, such as those arising from the use of pesticides and fertilizers. However, the external costs of growing fruits and vegetables are minuscule compared to those of producing animal foods. Plant-based foods, for example, generate virtually none of the health care costs and far less of the environmental costs that animal foods do.

12

Moreover, government subsidies are heavily skewed toward animal food producers, who receive more than thirty times the financial aid that fruit and vegetable growers do.

13

And like most features of meatonomics, these subsidies work in strange ways and have a number of unexpected consequences.

§

US agriculture is propped up by an intricate scaffold of government subsidies that would make Rube Goldberg proud. These programs funnel cash and benefits to big farmers in a variety of ways that most nonfarmers have never heard of, including crop insurance, disaster payments, and counter-cyclical payments, to name just a few. Few laypeople understand how these complex programs work, how pervasive they are, or the unexpected places they crop up. I was surprised to learn, for example, of a massive water subsidy program for farmers a few hours from where I live in Southern California. In California's Central Valley, irrigation subsidies let farmers use roughly one-fifth of the state's water and pay only a small fraction of its value—about 2 percent of what Los Angeles residents pay for water.

14

The farm subsidy system is filled with off-the-wall incongruities, the oddest of which lie in the federal government's conflicted policy agenda. On one hand, as we've seen, the USDA recommends in its

Dietary Guidelines for Americans

that we consume less cholesterol and saturated fat. On the other hand, it heavily subsidizes the foods that are the main sources of these substances—meat, fish, eggs, and dairy. On one hand, the

Dietary Guidelines

recommend that we eat more fruits and vegetables. On the other hand, the government designates these foods as specialty crops that are largely ineligible for subsidies. The net result: nearly two-thirds of government farming support goes to the animal foods that the government suggests we limit, while less than 2 percent goes to the fruits and vegetables it recommends we eat more of.

15

(The USDA, by the way, officially declined to comment on this or any other issues in this book.)

Perhaps even more surprising than our government's muddled messaging on agricultural subsidies is the total dollar value of these subsidies. The USDA will spend $30.8 billion in 2013 supporting US farmers with loans, insurance, research, marketing assistance, cheap water, and other help.

16

State and local governments will contribute another $26.5 billion, mainly in the form of irrigation subsidies.

17

That's a total of about $57.3 billion in annual government subsidies to

all segments of US agriculture—more than the entire annual government budget of New Zealand and twice that of the Philippines.

The lion's share of this subsidy largesse supports the animal food industry. Because most US corn and soybean crop is used for livestock feed, and most subsidies help farmers who grow these crops, most of the subsidies to US agriculture ultimately benefit producers of meat, eggs, and dairy. What kind of numbers are we talking about? One study estimates that 63 percent of US subsidies benefit animal food producers.

18

Applying this percentage to the $57.3 billion farm subsidy total, and adding $2.3 billion for fish subsidies (

see

chapter 9

), the total of annual subsidies to US producers of animal foods is an estimated $38.4 billion.

19

These subsidies work in surprising ways, and it's enlightening to consider whom they help and hurt. Supporters of farm subsidies argue that these programs provide a number of benefits, including assisting small farmers, boosting rural development, stabilizing commodity markets, and promoting national food security. However, subsidies typically work in ways far different from those intended.

Let's start with some historical perspective. When the Depression hit in 1929, prices of farm goods fell like corn stalks in a gale. President Franklin Roosevelt responded with New Deal programs, including subsidies, designed to stabilize prices and boost small farmers' incomes. The system worked at first, but as large farms came to dominate the agricultural landscape, less and less of the subsidy funds wound up in the little guys' pockets.

Today, the handouts are aimed at big farming concerns. Taxpayers paid out $161 billion in direct payment farm subsidies between 1995 and 2009, but two-thirds of US farmers didn't receive a cent. The funds mostly went to big corporate players, with one-fifth of recipients grabbing nine-tenths of the cash.

20

If the federal government sent invites to this party, those for small farmers were clearly lost in the mail. The 2013 farm bill (not yet passed as of this writing) seeks to end direct payments, the most controversial subsidy type, shifting the

funds to crop insurance instead. But the cash and benefits will still favor the big guys over the little family operations. Moreover, not only do most of the subsidy benefits go to large corporations, but most of the beneficiaries are in the animal food industry.

It may come as little surprise, but the handful of farmers who consistently harvest the most greenbacks from crop subsidies, research shows, are livestock producers. The reason: corn and soybeans are the main items on the menus for livestock, accounting for the majority of feed ingredients in factory farms (where virtually all US farm animals are raised).

21

This makes factory farms the biggest consumers of these subsidized commodities, and they buy most of the corn and soybeans grown in the United States.

22

Fish farms, by the way, also rely heavily on corn and soy for feed.

The expense of feeding hungry animals is a huge part of the cost of doing business in animal agriculture. This food accounts for almost half the costs of raising hogs and nearly two-thirds the costs of producing poultry and eggs.

23

But crop subsidies come to the rescue by helping producers keep their feed costs low. One study found that crop subsidies and the resulting lower feed prices allowed factory farms to decrease their operating costs by as much as 15 percent from 1997 to 2005, saving nearly $35 billion over the period.

24

As these programs favor big operators over small, they not only fail their original purpose of helping small farmers, but they also go a step farther and actually help drive small farmers from the rural landscape.

The problem isn't just that small farmers don't get their fair share of the subsidy pool. It's also that in light of the unintended effects these handouts have on the market, small farmers are among the biggest losers under subsidy programs. Subsidies distort the normal market forces of supply and demand, making small farmers overproduce even when inefficient to do so. For an example of math that doesn't really add up, consider: when subsidies reduce the market price of corn to levels

below

what it costs to produce, US farmers nevertheless continue to grow it in record amounts.

From 1986 to 2005, the cost to grow corn was higher than its market price in every year but one.

25

Yet because of market incentives to increase production levels, even as subsidy payments tripled during the second half of this period, farmers' net income fell by 15 percent.

26

It's not hard to see why. Say the cost to produce a bushel of corn is $6, but the bushel can only be sold for $5.90. No one's going to grow corn at these numbers. But throw in a $1 per bushel subsidy, and now there's profit of $0.90 per bushel. But as production increases, and the excess supply causes prices fall to $5.50 per bushel, farmers grow more corn to make up the income shortfall. This in turn drives prices even lower. It's a vicious cycle, a perpetual pattern of false cues and financial suffering for many of its participants. As physician Martin Fischer said, “Morphine and state relief are the same. You go dopey, feel better and are worse off.”

Supply management—holding goods in reserve—once kept these harmful forces in check. Remember government cheese? In the 1980s, the Reagan administration famously tapped tons of dairy reserves to give processed cheese to the poor. Criticized as the patronizing and unhealthy product of unrealistic and out-of-touch leadership, the orange, five-pound blocks became synonymous with Reaganomics and government double-speak. Still, despite evidence that supply management works, at least from a market perspective, policy makers abandoned that system in the 1990s for a market-oriented approach that deregulates supply. The theory was that with less regulation, farmers would make better choices—like producing less when prices dropped. Unfortunately, it turns out the theory was wrong.

In the world of small farms, subsidies are a poisoned chalice. Depressed commodity prices and smaller margins hurt small farmers' incomes. Not surprisingly, USDA research indicates that even with subsidies, most farm families don't earn enough farm income to support themselves.

27

Most of these families moonlight in off-farm activities, getting second (or third) jobs or engaging in other business activities to make ends meet.

28

This decline in income and lifestyle leads most small farmers and rural Americans to oppose subsidies; nearly two-thirds of Iowans, for example, favor eliminating subsidies.

29

The economic damage wrought by farm subsidies plays out regularly in rural communities across the country. In a 2007 article titled “Why Our Farm Policy Is Failing,”

Time Magazine

described the effect of subsidies on the small town of Randolph, Nebraska: