Methods of Persuasion: How to Use Psychology to Influence Human Behavior (15 page)

Read Methods of Persuasion: How to Use Psychology to Influence Human Behavior Online

Authors: Nick Kolenda

Tags: #human behavior, #psychology, #marketing, #influence, #self help, #consumer behavior, #advertising, #persuasion

In any case, whenever I hypnotize someone, I use that exercise to test that person’s level of hypnotizability. Though the test is by no means definitive, people who are hypnotizable generally show greater movement in their hands because their imagination causes their hands to move together more easily than people who are not as easily hypnotized.

The underlying principle behind that phenomenon is known as the

ideomotor response

, and it’s our tendency to perform behavior upon merely thinking about that behavior. People who are more easily affected by the ideomotor response will exhibit greater movement in their hands when they simply imagine their hands moving closer together. But the ideomotor response also applies to areas beyond mere body movements. For example, thinking about aggression can trigger aggressive behavior (much like priming), which is one of the key reasons why violence in video games and movies can increase aggressive behavior in children (Anderson & Bushman, 2001).

How does this principle relate to similarities? When we speak with people, we examine their nonverbal behavior and experience a hidden psychological urge to mimic that behavior. If someone is speaking with his arms crossed, you may soon find yourself with your own arms crossed. If that person is speaking with an enthusiastic tone, you may find yourself using a similar upbeat tone.

Though it occurs outside of our conscious awareness, this

chameleon effect

is a key element in building rapport (Lakin et al., 2003). Not only do we tend to mimic people that we like, but we also like people more when they mirror our own nonverbal behavior. In fact, researchers found the following outcomes when people imitated nonverbal behavior:

- Waitresses gained higher tips (Van Baaren et al., 2003).

- Sales clerks achieved higher sales and more positive evaluations (Jacob et al., 2011).

- More students agreed to write an essay for another student (Guéguen, Martin, & Meineri, 2011).

- Men evaluated women more favorably in speed dating (Guéguen, 2009).

Thus, not only do “incidental similarities” result in a greater likelihood to comply with a request, but so too does similar nonverbal behavior.

In addition to evolution and implicit egotism (the two reasons that were described earlier in the chapter), another reason why similar nonverbal behavior is so powerful can be found in our brain’s desire for symmetry. When another person imitates our nonverbal behavior, this symmetry activates the medial orbitofrontal cortex and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, brain regions that are associated with reward processing (Kühn et al., 2010). Mimicking behavior is so powerful because, in a way, the symmetry is biologically pleasing.

There are two basic strategies you can use to take advantage of this principle. The first should be pretty obvious: to gain compliance, you should build greater rapport by mimicking your target’s nonverbal behavior. Commonly used by therapists to convey empathy (Catherall, 2004), this strategy has been implemented in various settings with remarkable success (as you can see in the previous list of experimental outcomes).

Due to the powerful impact of mimicking nonverbal behavior, you should always strive to make your request in person. Although that advice may sound somewhat foreign due to our technology- and e-mail-obsessed society, you’re more likely to gain compliance when you make a request in person (Drolet & Morris, 2000). If your situation isn’t conducive for an in-person interaction (e.g., far distance), you should use video conferencing or, at the very least, a phone call. The more nonverbal cues that are available, the more easily you can mimic them to build rapport with your target, which will increase your chances of gaining compliance.

To understand the second strategy of mimicry, think back to the concept of congruent attitudes and how we infer our attitudes by observing our body language and behavior. Remarkably, research reveals that we sometimes infer our attitudes by observing the behavior of others who we perceive to be similar to us. Using an EEG (a brainwave recording device), Noah Goldstein and Robert Cialdini (2007) led people to believe that they shared similar brainwave patterns with a student who appeared in a video interview, an interview that depicted the student’s altruistic efforts toward helping the homeless. When the researchers asked participants to complete a questionnaire after watching the interview, people who were informed of the similar EEG patterns not only rated themselves to be more self-sacrificing and sensitive, but they were also significantly more likely to help the researchers in an additional study. People were more likely to assist in the additional study because they observed the altruistic behavior from the supposedly similar student, and they developed a congruent attitude from that student’s behavior.

If your target perceives you to be similar, she will develop attitudes that are congruent with

your

behavior. Therefore, if your target perceives you to be similar, you should display behavior that’s consistent with the attitude that you’re trying to extract from your target. For instance, if one of your close friends is starting to struggle in school, you should make an effort to have occasional study sessions together, even if you’re not in the same class. The simple exposure to seeing you study might help your friend develop a genuine interest in studying more, which could help boost her grades. Even if you simply talk about your interest in the material from your class, you could help your friend develop a congruent attitude that she’s also interested in the material from her classes.

A MIND READER’S PERSPECTIVE: HOW TO FREAK PEOPLE OUT USING THE IDEOMOTOR RESPONSE

Want to freak people out? Many psychological principles, such as the ideomotor response, can seem simplistic; but with enough showmanship, you can make these simplistic techniques seem like powerful miracles. This section describes one demonstration that you can use to truly freak people out.

First, find any pendulum type of object (an object attached to the end of a string that will swing back and forth). If you hold the end of the string steady and leave about 8 inches of string for the object to swing freely in the air, you’ll find that merely thinking about a direction will cause the object to swing in the direction that you’re imagining. If you think about the pendulum swinging left and right, the pendulum will start swinging left and right. If you think about the pendulum swinging forward and back, it’ll start swinging forward and back. Because of the ideomotor response, your hand will be making minuscule movements to move the pendulum, but the funny part is that you won’t even feel your hand moving at all; it’ll seem like you’re controlling the pendulum with your mind. It’s pretty freaky.

But here’s where your showmanship can make this principle seem like a miracle. If you bring a pendulum to your friend, you can describe how that pendulum has certain “powers.” To demonstrate, you ask your friend to think of something (let’s assume that you ask him to think of a playing card, and let’s assume that he thinks of the Jack of Clubs). You instruct him to hold the end of the string so that the attached object hangs freely, and you explain that swinging forward and back means “yes” and that swinging left and right means “no.”

After you give these basic instructions, you proceed to ask him yes or no questions about the playing card to narrow down the options, and you tell him to merely think of his answer. When he thinks of his answer, the pendulum will swing in the appropriate direction because of the ideomotor response, but your friend won’t realize it. It’ll seem like the pendulum is moving on its own.

For example, your first question could be, “Is your card red?” This would cause your friend to think “no” because his card was the Jack of Clubs. If you ask him to concentrate on his answer, the pendulum will start to move a little sporadically, but you’ll find that it’ll start to move consistently from side to side, indicating a negative answer.

You can then ask additional questions (e.g., is your card a club, is your card a royal card) to narrow down the possibilities. After about five or six “yes” or “no” questions, you can divine the playing card that your friend never even mentioned out loud, and your friend will have no idea that it was the ideomotor response that caused the pendulum to swing in those directions. Though a simple principle, this demonstration can seem like a miraculous phenomenon to people.

REAL WORLD APPLICATION: HOW TO BOOST SALES

In this Real World Application, based on a study by Wansink, Kent, and Hoch (1998), you’re a manager at a supermarket, and you decide to use anchoring, limitations (the topic of Chapter 13), and social pressure to boost sales of a particular item.

Near the shelves that display the cans of Campbell’s soup, you hang a sign that says, “Limit of 12 per person.” Albeit an innocent sign, that statement packs a powerful punch for a few reasons. First, the number 12 sets an anchor that people assimilate toward. Rather than purchase 1 or 2 cans, people are influenced by that anchor to purchase a larger number of cans. Second, as you’ll learn in Chapter 13, limiting the ability to purchase those cans will spark “psychological reactance,” and it’ll spark a greater desire to purchase cans of soup. Third, that sign triggers social pressure by implying that the cans of soup are very popular (why else would the store be limiting the number of cans that people can purchase?).

In the actual study, the researchers included three variations of that sign, and they measured how many cans people purchased with each sign:

- “No limit per person” generated an average of 3.3 cans sold.

- “Limit of 4 per person” generated an average of 3.5 cans sold.

- “Limit of 12 per person” generated an average of 7.0 cans sold.

Remarkably, the original 12-limit sign generated sales that were nearly double those of the other signs.

If you wanted to further enhance the effectiveness of that sign, you could even change the wording to say, “Limit of 12 per customer” or “Limit of 12 per [Supermarket Name] customers.” That small wording change takes advantage of ingroup favoritism by emphasizing that people from the same ingroup (i.e., customers) are purchasing those cans of soup. Much like the hotel influenced people to reuse their towels when they emphasized that guests from the same room reused their towels, when you narrow the focus from “person” to “customer” or “[Supermarket Name] customers,” you can exert even more pressure on people to purchase those cans of soup (or any other item for that matter).

STEP 4

Habituate Your Message

OVERVIEW: HABITUATE YOUR MESSAGE

ha·bit·u·ate

To become accustomed or used to something

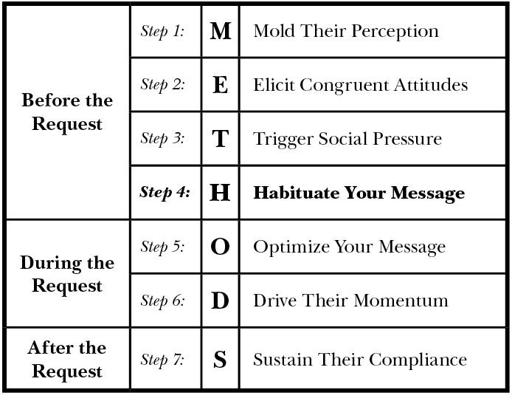

We’re almost there! There’s just one final step to implement before you make your actual request. Now that you’ve molded your target’s perception, elicited a congruent attitude, and triggered social pressure, this next step involves habituating your message.

The first chapter in this step will explain why making your target more familiar with your request (via repeated exposures to the general topic) can make that person more likely to comply with your request. The second chapter in this step will explain a clever strategy that uses habituation to desensitize people to any message or request that you know they will find unfavorable. Once you complete this step, the next step will be to present your actual message.

CHAPTER 8

Use Repeated Exposures

If you had to guess, which picture of yourself do you think you’d prefer: an actual picture or a picture of your mirrored reflection? I’ll give you a few paragraphs to think about it.

When I tried my first beer in college, I thought it tasted disgusting. I hated it. I started arguing with my friends because I thought they were crazy for enjoying the taste. They argued with me by saying that I would eventually learn to like it, but I still thought they were crazy.

It wasn’t until my third or fourth beer until I finally realized that my friends were right. Although I initially hated my first few beers, I gradually developed an appreciation for the taste over time, and now I love the taste of beer. How could that be? How could something that I found so disgusting and repulsive become something that I now find very pleasant?