Methods of Persuasion: How to Use Psychology to Influence Human Behavior (26 page)

Read Methods of Persuasion: How to Use Psychology to Influence Human Behavior Online

Authors: Nick Kolenda

Tags: #human behavior, #psychology, #marketing, #influence, #self help, #consumer behavior, #advertising, #persuasion

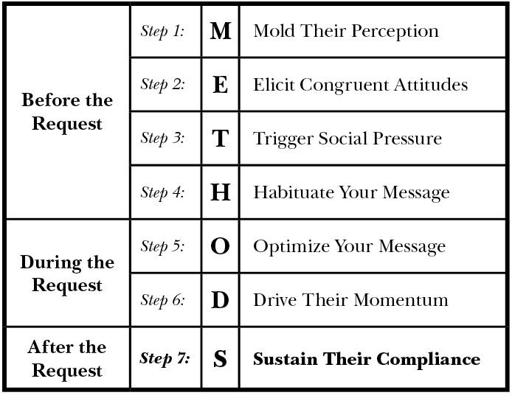

STEP 7

Sustain Their Compliance

OVERVIEW: SUSTAIN THEIR COMPLIANCE

So what was the verdict? Did your target comply with your request? Whether or not your target complied, you should still use the strategies in this seventh step of METHODS. The purpose of this step is two-fold. You can:

- Use these strategies to sustain your target’s compliance, or . . .

- Use these strategies on an ongoing basis if you failed to secure their compliance.

Assuming that your target complied, there are many situations where you need to maintain that compliance, especially if your request involves a long-term change in behavior (e.g., trying to influence your spouse to eat healthier).

And if you still haven’t gained their compliance, don’t fret. You can use the strategies in this step to continuously exert pressure on your target over time so that they eventually cave and comply with your request. When your request has no strict deadline, there’s no end to the persuasion process.

CHAPTER 14

Make Favorable Associations

As you could probably predict after learning about the recency effect in Chapter 11, I purposely ensured that this last chapter was very interesting and important (which is my attempt to leave you with a lasting positive memory for this book). Although it’s presented last, this chapter actually forms the basis of the entire book because it encompasses schemas and priming, the topic of the very first chapter. Once you read this chapter, you’ll understand why METHODS isn’t a linear step-by-step sequence, but rather, a circular and ongoing process.

What’s this chapter about? Some random food products can help explain. Mentally rate each of the three items in the following image in terms of how much you enjoy consuming it (1 = not at all, 10 = very much).

If you can’t tell by looking at the image, the three products (from left to right) are oatmeal, mayonnaise, and coffee.

Do you have your rating? You may not have consciously realized it, but the mayonnaise in the middle likely affected your rating of the outer products (i.e., the oatmeal and the coffee). Why? Research shows that mayonnaise can spark feelings of “disgust,” which can then be transferred to other products that are in contact with that item, an effect known as

product contagion

.

In a series of experiments examining product contagion, Morales and Fitzsimons (2007) presented people with a small shopping cart containing a few items, and they positioned some “feminine napkins” so that they were resting slightly on a box of cookies in that shopping cart. Even though everything was still packaged and unopened, the researchers discovered that this slight contact made people significantly less likely to want to try those cookies. When they presented a different group of people with those same items but with six inches of space between those products, that negative perception virtually disappeared. The researchers also found that product contagion occurs when the target item is non-consumable (e.g., notebooks) and that the effect becomes stronger when the packaging of the disgusting item is clear or transparent.

The main point I’m trying to illustrate with that study is that certain features from one stimulus can easily transfer to another stimulus, an implication that stems far beyond proper shelving in supermarkets. This chapter will explain a similar psychological principle and how you can transfer favorable qualities to your message via some type of association with another stimulus.

WHY ARE ASSOCIATIONS SO POWERFUL?

It all started with a group of dogs. Dogs? Yep, dogs. Pavlov’s dogs, to be more precise.

In 1927, Ivan Pavlov, the founder of what would become the most fundamental principle in all of psychology, stumbled upon his discovery when he was researching digestion in laboratory dogs (a very lucky accident for the field of psychology). He started noticing that whenever the lab assistant would enter the room with meat powder for the dogs, the dogs would start to salivate even before they could see or smell the meat. Like any rational researcher, Pavlov assumed that the dogs didn’t posses some type of telepathic power but were instead being influenced by some scientific principle. And his hunch was right.

After developing the belief that the dogs were somehow being conditioned to

expect

the arrival of the meat, Pavlov conducted a series of experiments to test his prediction. He first examined whether his dogs would respond to a neutral stimulus, such as the ringing of a bell. When no particular response occurred, he started pairing the bell with the presentation of the meat powder; immediately before presenting the dogs with meat powder, he would repeatedly ring the bell. Before long, the dogs started associating the bell with the meat, and they would start to salivate upon Pavlov merely ringing the bell. Thus, he found:

Bell --> No Salivation

Bell + Meat --> Salivation

Bell --> Salivation

Pavlov concluded that a neutral stimulus that elicits no behavioral response (e.g., a bell) can start to elicit a response if it becomes paired with an “unconditioned stimulus,” a stimulus that

does

elicit a natural response (e.g., meat that elicits salivation). Albeit a simple finding, that idea of

classical conditioning

launched a new era in psychology.

Why does it work? The most common explanation is that if a neutral stimulus (e.g., bell) is repeatedly presented before an unconditioned stimulus (e.g., meat), then the neutral stimulus becomes a signal that the unconditioned stimulus is arriving (Baeyens et al., 1992). When Pavlov repeatedly rang the bell before presenting the meat, the dogs became conditioned to

expect

the arrival of the meat, and so they began salivating with a mere ring of the bell.

But that’s not the only explanation. Far from it, in fact. Although the neutral stimulus is typically presented before the unconditioned stimulus, research shows that conditioning can occur even if the unconditioned stimulus (the response-provoking stimulus) is presented before the neutral stimulus, a form of classical conditioning known as

backward conditioning

or

affective priming

(Krosnick et al., 1992). If you present an unconditioned stimulus that elicits some type of affective/emotional state, you are essentially priming people to view a subsequent neutral stimulus through the lens of their new emotional mindset (hence the term “affective priming”). Accordingly, those emotional feelings can influence people’s perception and evaluation of that neutral stimulus.

Suppose that you consistently phone your friend when the weather is beautiful. In this situation, you would be using affective priming to associate yourself with beautiful weather:

You --> No Response

You + Beautiful Weather --> Positive Response

You --> Positive Response

With enough pairings, your target would begin to associate the positive feelings that naturally occur from the beautiful weather with you. In other words, you become the bell from Pavlov’s experiment, except instead of producing salivation, you’ll produce a positive emotion when your target sees you.

Besides affective priming, there are other reasons why your target would come to associate you with the positive emotions produced from beautiful weather. The rest of this section will describe two additional explanations.

Misattribution.

One of the main ideas that you should take away from this book is that we tend to make misattributions. Take processing fluency as an example. That principle can explain why stocks with easy-to-pronounce ticker symbols (e.g., KAR) significantly outperform stocks with ticker symbols that are difficult to pronounce (e.g., RDO) (Alter & Oppenheimer, 2006). People mistakenly attribute the ease with which they process a ticker symbol with the strength of a company’s financials; if a ticker symbol is easy to pronounce, the positive feelings that emerge from that quick processing get misattributed to the underlying financials of that company.

In classical conditioning, we make similar misattributions (Jones, Fazio, & Olson, 2010). If two stimuli become associated with each other, we can misattribute the feelings produced from one stimulus as stemming from the other stimulus. When we view humorous advertisements, for instance, we tend to misattribute the positive emotions that we experience from the humor as emerging from the product being advertised (Strick et al., 2011).

Remember the example where you (the neutral stimulus) associated yourself with good weather (the unconditioned stimulus)? Like some readers, you might have quickly brushed over that tidbit because it seemed far-fetched (let’s face it, it does

seem

far-fetched). But research suggests that this claim may have some merit. Schwarz and Clore (1983) telephoned people on either a sunny or rainy day to assess their well-being, and remarkably, people were significantly happier and more satisfied with their life when the weather was sunny. But what’s interesting is that the misattribution error disappeared for many people when the researchers began the conversation by asking, “How’s the weather down there?” When people in the rainy condition were asked that innocent question, they consciously or nonconsciously realized that their dampened mood was due to the weather, and they adjusted their happiness ratings upward.

Here’s the main takeaway: associations are powerful because we can easily misattribute characteristics and responses from one stimulus as emerging from another stimulus (and if you’re thinking about calling up an old friend, it might not be a bad idea to wait until the weather is nice). The next section will explain one final reason behind the power of associations: our semantic network.

Semantic Network.

As Chapter 1 explained, our brain has a semantic network, an interconnected web of knowledge containing everything that we’ve learned over time, and every concept (or “node”) in that network is connected to other concepts that are similar or associated. Further, when one concept becomes activated, all other connected concepts become activated as well, a principle known as spreading activation. All of that was discussed in the first chapter.

This final chapter truly comes full-circle because associations can explain how that semantic network came into existence. Every concept that we’ve learned over time (i.e., every node in our semantic network) has emerged through an association. Whenever we’re presented with a new concept, we can’t simply place that concept free-floating in our brain; in order to successfully integrate that new concept into our existing network of knowledge, we need to attach it to an already existing concept via some type of similarity or association.

To illustrate, read the following passage that researchers gave to people in a clever research study:

The procedure is actually quite simple. First you arrange things into different groups depending on their makeup. Of course, one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. If you have to go somewhere else due to lack of facilities that is the next step, otherwise you are pretty well set. It is important not to overdo any particular endeavor. That is, it is better to do too few things at once than too many. In the short run, this may not seem important, but complications from doing too many can easily arise. A mistake can be expensive as well. The manipulation of the appropriate mechanisms should be self-explanatory, and we need not dwell on it here. At first the whole procedure will seem complicated. Soon, however, it will become just another facet of life. It is difficult to foresee any end to the necessity for this task in the immediate future, but then one never can tell. (Bransford & Johnson, 1972, p. 722)