Mr Cricket (7 page)

L

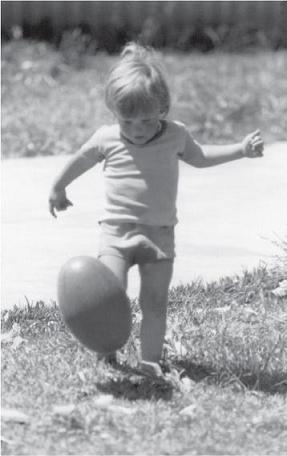

ike generations of Australian kids before me, I was introduced to cricket in the backyard of the family home. It wasn't your standard introduction, though. We didn't have any tennis balls when I first started hassling Dad to play with me, so he put a stick in my hands and threw rocks at me. Alright, maybe not at me! He'd lob up these little bluish coloured pebbles from the beach nearby and I'd do my best to connect. I was only about four years old at the time, so I guess it was a pretty good start at building handâeye coordination.

Soon Dad made a little bat for me out of old wood and bought a few tennis balls. But cricket really wasn't Dad's thing. He was into other sports. So, when David, two years my junior, was old enough to play it was great because I had someone else around who was energetic and loved cricket. It was the early 1980s and the Australian team was battling hard. There were some great characters in the team that caught our attention and we would watch cricket for hours on TV. Afterwards, we would go out to the backyard and pretend to be our heroes. I loved Allan Border, Dennis Lillee and Rod Marsh. DK was a favourite. Though Dad exposed us to lots of different sports very early on in the piece, the lure of charging in off the long run (the full length of the driveway, that is) and doing the big double-armed, low-crouching Lillee appeal was too great. Poor old Dad just had to put up with it.

Our backyard was perfect. Mum and Dad had moved to the house at Mullaloo â about 30 minutes out of Perth â in the early 1970s because, frankly, it was all they could afford. There were only a couple of houses in the area when they moved there but it didn't matter to them. The block was quite big, it was close to the beach and, as young parents, they felt those things were more important than being in the thick of the city action. It must have been the right choice because they still live there.

Never, never, never quit

Living on the outskirts of Perth was fine with David and me because it meant we had plenty of space to run around and, most importantly, plenty of room to play cricket. The rules for our games were your standard backyard fare: over the fence was out (which fitted

in nicely with Dad's advice to keep the ball on the ground) and it was automatic wickie. Batting under the carport made it hard to clear the fence, anyway, though a clean strike through cover would do the trick. It was the same handicap for each of us, as back then we were both right-handers.

We always got excited about our backyard cricket games â they were very competitive. And, when I say competitive, I don't just mean that Dave and I would try to outdo each other with skill and honour. No, this wasn't a case of best man wins. It was far more sinister than that. And, there is absolutely no doubt about it, Dave was entirely to blame.

He would blackmail me. He knew that I was desperate to get outside and play so he would bribe me and make me let him bat first. Always. I could put up with that, just. But then, when he was out and it was my turn to bat, he'd always find a reason why he was not out! In fact, Dave was never out. If he nicked one to the keeper, he wouldn't walk. Even if he got clean bowled he refused to hand over the bat! It was then that the fights would start.

These fights were spectacular. I would chase Dave around the backyard trying to give him a clip behind the ear because he was out and wouldn't hand over the bat. He'd be screaming, I'd be screaming, Mum would be yelling, Dad would be shaking his head. It was all happening, as Bill Lawry would say. Inevitably, Dave would chicken out and lock himself in the car and refuse to come out. That's how so many of our games ended: him in tears running away from me and me crying because I'd been hoodwinked again into bowling for ages and not getting to bat. Dave certainly has some questions to answer about the dodgy tactics he relied on back then. But, no matter how dramatic (and loud) our one-on-one games of cricket were in those days, I do suspect something resembling that sort of scene was â and hopefully always will be â played out in an endless number of backyards across the country each summer.

My childhood was your stereotypical Australian childhood. But my parents not only made good people out of us kids, they unwittingly taught us virtually all the basic lessons a professional sportsperson needs to learn.

Dad loved athletics and was pretty good at it. He was due to try out for the Commonwealth Games one year, but the week before the trials, unfortunately, he blew out his ankle playing basketball. He says these days that he wouldn't have made the team but I know from other people that he was a very good 100- and 200-metre sprinter and probably undersells himself a little when he reminisces.

He also had a particular fascination with coaching and the art of motivation. Over many years of involvement in sport, he coached soccer, my mum's netball team, athletics and, eventually, cricket and was a player-coach in basketball. He became interested in the preparation of players and later, finally accepting of the fact his boys were nuts about cricket, he became very interested in how to prepare players for cricket and he applied his athletics background to it. He thought cricket was very much a game of balance and learning to run correctly and he spent many hours teaching us to do those things well.

Dad applied that work ethic away from sport too. He was employed at the post office for many years and, later, went into public relations for the public transport authority, TransPerth. He was an only child who had come from a modest background, growing up around Mount Hawthorn, a working-class suburb of Perth. Like most Aussie battlers, he grew up well aware of the distinction between time for leisure and time for work. When it was time for work, he would really knuckle down and bring out that raspy Australian voice that I still have ringing in my ears. âIf it's worth doing, it's worth doing properly!' was one of his favourite sayings.

The price of success is hard work, dedication to the job at hand and the determination that whether we win, lose or draw, we have applied the best of ourselves to the task at hand.

Dad showed us the sporting qualities we needed. My mum, Helen, meanwhile, taught me some other very valuable lessons that I believe went a long way to preparing me to represent Australia. Mum was mostly relaxed around us when it came to sport. âGo out and play. Have a good time,' she'd say, shooing us away. But around the house it was a different story. In that setting she was very much the disciplinarian. When it came time to do housework or schoolwork she was very strict and ensured that we did those tasks thoroughly. Being kids, we always tried to stretch the boundaries to see what we could get away with. But if we pushed it too far, Mum would get very angry.

One particular bee in her bonnet was bad manners. Mum insisted that Dave, my sisters Kate, Gemma and I presented well and come across as well-rounded individuals. That meant dressing appropriately, speaking well, being polite and having good manners â especially while eating. If we didn't do those things well she would come down on us in a big way.

Probably the best way to explain what I mean here is to use the example of peas. Yes, peas. Now, everyone knows how tricky it is to eat peas. Once you've managed to get a few on your fork, you have to somehow get the fork from plate to mouth without them falling off. All Dave and I wanted to do was shove food into our mouths as quickly as possible but Mum was quite insistent on the proper way to do it. âYou have to push the peas to the back of your fork and lift them to your mouth slowly,' she would say. Dave and I would roll our eyes.

Big Merv Hughes must have been playing for Australia around that time and, with us being cricket mad, Mum thought she could relay her point better by dropping the name of one of our heroes: âCould you imagine playing Test cricket with Merv Hughes, sitting at the lunch table and eating your peas like that?' Having gotten to know Merv since then, I think Mum could probably have used a better example, but she got the point across.

So manners and presentation were under control from an early age. But sport was our driving force. While cricket was our obsession each summer, in winter we both loved Australian Rules football. The backyard would be transformed from Lords to Subiaco Oval. If we weren't playing in the backyard, we'd be at the local park.

Dad thought it was imperative for us to be able to kick with both feet. We're not just talking about simple punts. It meant having the full arsenal of tricks: drop kicks, drop punts, torpedoes and running drop punts â all with both feet. Remember, if it was worth doing, it was worth doing as well as possible. So, Dad devised a system to teach us this ability. We would start at about 10 metres and execute each type of kick for a goal off each foot before we could go up to the next distance, which was 15 metres. Then we'd master that distance and move on to the next. The last distance I remember being tested from was about 35 metres, which I thought was pretty good for a couple of pre-teen kids. We enjoyed it, too, because we could notice ourselves gaining skills and it was another chance for us to compete against each other.

I ended up playing two seasons of competitive footy, between the ages of 11 and 12. But, as much as I enjoyed it, it was never going to do much for my personal wellbeing. Being such a small kid, the best position they could find for me was rover. Basically, that meant the ruckman would tap it down to me â and I'd get immediately barrelled to the ground. The next time there was a tap, I'd get the ball and get smashed again. I loved football, appreciated the skills involved and enjoyed playing in a team environment, even on days when it was cold and rainy, but I wasn't so sure I enjoyed getting smashed 20 times a game and didn't see too much of a future in the sport for me. At one point I actually became quite worried that I was going to get badly hurt.

Another reason I turned away from football was because of squash. The guy who lived two doors up from us, Mike Wheeler, built and started a squash centre in our local area and Mum was very adamant that we should support him. It was a new business and he was a really good man and Mum thought it our duty to help him out, so Dave and I would ride our bikes up to the centre every day or two and have a hit. On Friday afternoons and Saturday mornings Mike would teach us to play and then we'd have competitive matches. Mike was a brilliant coach and made learning the game exciting and interesting. We enjoyed squash, got right into it and, having good handâeye co-ordination and fitness, we both did pretty well. But the main thing was that it was fun. It became much more competitive as we got older, though I reckon it was the only sport in which Dave and I didn't try to kill each other. I was always slightly better than he was, but our games would never end in tears or fights. You'd have to ask Dave why.

I became pretty good at squash and went through a stage of taking it quite seriously. But I lost heart around the age of 16 because, for all my effort, I couldn't get past the two best players in the state. And being No. 3 was a curse because the national tournaments involved only the top two players in each age group. They'd pick a third player but he would stay in Perth on standby in case someone got injured.

I tried to beat the other two but they were just too good and I never got to go on a tour. I was very disappointed about that and, being so competitive, I used to beat myself up every time I lost or played badly. However, all was not lost. Squash at least lifted my fitness and taught me about touch and placement. So when I got more and more involved in cricket, it certainly helped. I was trying to perfect both sports but it soon became apparent that the amount of time I was putting into the two pursuits was unsustainable. Something had to give. I had to choose one over the other and, in the end, it was quite an easy decision to make.

Once my decision had been made, Dad clicked into gear and started giving us advice on how both David and I could improve as cricketers, physically and mentally. By the time I was playing for Wanneroo, he'd become heavily involved in our team's training program, especially the pre-season.

During the first month, we'd meet on Sunday mornings about 10am and go for a four- or five-kilometre run along the soft sand at the beach. For the next 10 weeks we graduated to the sand hill, where Dad had marked out a track for us to follow. This track was about 800 metres long and everyone was timed. The intention, of course, was to better your time each lap. In the first week we'd do three laps, the following Sunday we'd do four laps and it would increase by one each week for 10 weeks. For the last five or six weeks leading into the season Dad would take us to the club and we'd work on skills and running on grass.

The whole running and fitness thing wasn't everyone's cup of tea. And it was optional. Some guys would go for a couple of weeks and then miss the next couple. Some wouldn't come at all. Some had families and had better things to do with their Sunday mornings. But for Dave and I there was really no choice, as our Dad was the trainer!