Mr Cricket (4 page)

But it's not just inexperienced players who need to be fostered in such a manner. The more I've learned about professional cricketers and sportspeople in general in recent years, the more I've realised that the image of us being fearless and confident is sometimes off the mark. Not that the public could be blamed for having such a perception. We travel the world representing our country, getting well rewarded for expressing our talents and doing something we love. We often look a picture of health and spend a lot of time celebrating success, with our chests out and our heads held high. But you would be surprised how many top sportspeople have spent years and years learning to overcome their fears, the kind of fears most people have in their everyday lives: fear of failure, fear of what others think of you or fear of being overwhelmed. If you've made it to playing for the Australian cricket team, chances are you've gone a long way to dealing with those problems effectively and in a way that works for you. But I know for a fact that some of the cricketers who appear most confident have to work very hard to stay positive and beat their insecurities. I am certainly one of them.

Recently I was thinking about different points in my career in the search for a time that I could, perhaps in retrospect, feel satisfied. Surprisingly, I found that the time I felt most comfortable in myself â and possibly, therefore, most successful â was shortly after I experienced my worst moment in cricket.

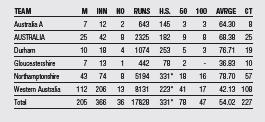

MICHAEL HUSSEY

FIRST CLASS STATISTICS

I put an increasing amount of pressure on myself throughout the late 1990s, desperate to progress past state level and play for my country. I'd had four or five good seasons for WA, in which I'd scored over 900 runs each, but hadn't got an opportunity to play for Australia. I felt like I was doing everything I could: training hard, scoring runs â ticking all the boxes. But the guys who were in the Test team were all playing so well and opportunities were hardly ever available.

Matthew Hayden and Justin Langer were belting teams, Ricky Ponting and Adam Gilchrist were also very aggressive and I started to feel as though the only way I would get an opportunity was if I started to bat more like them, to be more attacking and dominate every bowling attack I faced. The problem was that I was the kind of batsman who preferred to be patient. I wanted to bat all day, not score six or seven runs an over like the Test guys were. I started trying to second guess the selectors. âWhat do they want? I have to do something to make myself better or more attractive to them.' I came to the conclusion that because the guys in the Australian team were all scoring so quickly, I had to change my game to be more aggressive. It turned out to be a disaster because I left behind the very basis of what had made me a good batsman.

The result was three seasons in which I performed inconsistently. My form was varied, my focus was muddled and I was trying to be something I wasn't. In the end, I played myself out of the team. I was dropped for the last game of the 2002â03 season. I felt like my career was over. It was a defining moment in my career and one that was to influence the rest of my life.

That winter I went to England â where I never had too many problems scoring runs â and set about restoring my confidence. I knew, however, that I needed to truly reassess the way I went about things. I remember on a visit back to Perth, Amy and I had a conversation where we tried to work out how I could get my career back on track. Amy is always so measured and calm and she made me cut through all the crap and get back to what was important. Our conclusion at the end of the conversation was that, from that point on, as unbelievable as it might sound,

I would no longer worry about playing for Australia. When I came back to Australia to play club cricket I vowed to play my natural game, find enjoyment in cricket again and work my way back into the state side.

1997 PRE-SEASON GOALS:

TECHNICAL

Batting: drives and batswing, cuts, pulls, lofting spinners

Batting: drives and batswing, cuts, pulls, lofting spinners

Bowling: run-up, through the crease, get video done

Bowling: run-up, through the crease, get video done

Fielding: run-outs â diving saves (specific exercises), lots of catching (slips and cover), foxing

Fielding: run-outs â diving saves (specific exercises), lots of catching (slips and cover), foxing

PHYSICAL

Stronger â weights, boxing, agility, fitter in all aspects (morning work, do more work, extra work)

Stronger â weights, boxing, agility, fitter in all aspects (morning work, do more work, extra work)

During season, fresher program â yoga, tai chi

During season, fresher program â yoga, tai chi

MENTAL

Situation assessment, make 200s (think about it), attention to sledging, practise routines (look like nothing fazes me), body awareness during pre-season and season.

Situation assessment, make 200s (think about it), attention to sledging, practise routines (look like nothing fazes me), body awareness during pre-season and season.

Make no mistake, I was shattered when I was dropped by WA. But I truly think that, with the revised attitude I took in to the new season, even if I'd been dropped again and never played another game, I would have been able to cope a lot better simply because I'd been true to myself. As it turned out, I didn't get dropped again. Ever. I no longer tried to be someone I wasn't. I no longer tried to keep up with the Joneses â or the Haydens, Gilchrists and Pontings.

I backed up my good English county season with a few runs in Perth club cricket and was picked again for WA for the opening game of the new summer. I was back and next thing I scored a double century.

I knew straight away that the reason I was performing well was because I'd gone back to basics. I had re-acquainted myself with the reasons I started playing cricket in the first place. I was once again simply enjoying the game and everything that comes with it. Perhaps the fact that I was back playing my style of cricket â and regaining a sense of comfort with who I was, how I played and where I was at â was my true indicator of success. After several years of trying to please everyone but myself, I could safely say that I was once again free to be me.

Feeling liberated on the field is directly related to having an understanding of your place within a team. Way before I started playing for WA I began learning about the methods needed to feel like a valued part of a team. At Wanneroo, my second club, I learned a lot about cricket and the team environment. But I was quite a late developer and therefore always smaller than the other kids. I couldn't hit the ball hard and scored the bulk of my runs by deflecting and gliding it behind square leg or point. I did little more than just hang around at the crease for as long as I could. I honestly felt I was quite a boring batsman to watch.

My first coach at Whitfords, Bob Mitchell, had told me that, because I had little power, I should concentrate on technique, defence and just try to survive at the crease. As I developed physically, Bob explained, my good technique would hold me in good stead. He was right. But while those years were helpful in providing me with a good technique, I couldn't help feeling a bit envious of the bigger boys, who seemed to have no trouble smashing the ball around. They looked so powerful and aggressive and I wanted to appear that way too but physically I couldn't match them. Though I did get a chance.

One damp and cold Thursday afternoon we were training on tatty old astroturf mats, which, for good measure, had tree roots growing underneath them. It was like batting on corrugated iron. The ball was bouncing and popping all over the place. Everything was wet and dim and there I was facing Peter Clough. Peter was a giant, well over six feet tall and had taken 139 wickets in 43 first-class matches for Tasmania and Western Australia. He didn't care that I was a puny 17-year-old and came charging in off the long run-up to terrify me. It worked and, not surprisingly, I batted poorly and hardly laid bat on ball. I was churned up afterwards, partly happy to have survived in one piece, but also disappointed I didn't perform better. I couldn't wait to get out of the nets. Just as I did, our A-grade captain Damien Martyn and the club coach Ian Kevan came over to tell me I was ready to make my A-grade debut. After barely surviving Clough for half an hour, I found it surprising that they felt I was ready to join the top team, but I wasn't about to knock them back.